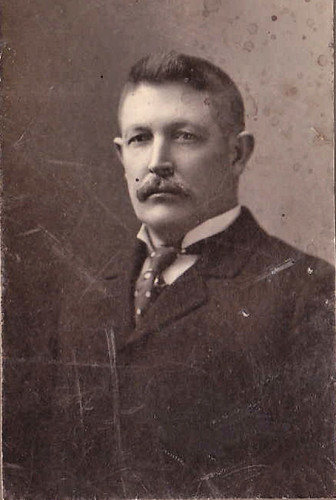

In the not too distant past we published a post about Hardy Hardella and his dog Moxie. Hardy and Moxie are among our favorite Joplin residents, so when we found an article about Hardy and his days with the circus, we knew it would end up as a post. A more specific post on Hardy himself is in the works for later.

Hardy Hardella moved to Joplin in 1905. A few years later, one of Hardella’s old circus cronies arrived in town. The two had not seen each other in twenty-five years, but Hardy and William Underwood (his stage name was William Lucifer) took up where they left off the last time they had seen one another. Underwood, still working the vaudeville circuit, arrived in Joplin for a performance and decided to call upon his old friend.

The two men first met when they worked together in the Charles Hunter Circus which traveled through Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. Hunter, the former circus owner, still lived in the area, but instead of wrangling animals and acrobats, now proprietor of the Crescent Hotel in Pittsburg, Kansas. The two men said the circus consisted of one car, a camel, two ponies, six or seven mules, and two or three horses. Altogether there were twenty five men employed by the circus.

The circus car, an old condemned Pullman, had a secret compartment underneath it. When times were hard, half of the employees would hide in it when the conductor came around to collect train fares. One day, however, Hunter’s adopted son poked his head up out of the trap door when the conductor came through. Hunter’s circus “had hard luck on that road ever after.”

Underwood recalled the time he came to Joplin with the De Haven Circus and a fight broke out between circus employees and local miners. Angry miners cut up and destroyed the circus tents and half of the outfit was “broken up.”

After things seemed to have cooled down, another fight broke out after miners and circus workers got into a brawl at one of Joplin’s saloons. Underwood remembered “billiard cues and bottles were freely used” in the fight. Circus workers were arrested and thrown in Joplin’s city jail for a few days before they were released. Underwood remarked, “I have never forgotten that incident in Joplin. I have been all over the world since then and in every civilized nation, but I nearly always sign my residence as Joplin, MO., because of that fight and subsequent stay in jail.”

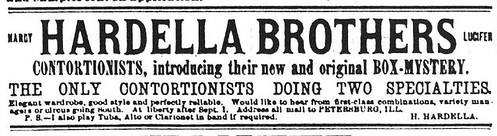

That same week, Hardy Hardella and William Underwood met old friend William McCall, who performed with Hardella as the “Hardella Brothers,” to discuss old times. The men recalled when Hardy was known as, “Hardella, the wonderful contortionist.”

Underwood remembered how the “old time circuses sure used to clean out a town. There was always a bunch of ‘fakirs’ that went along with the show and paid big concessions. The games they used to devise were many and varied. Yankee ingenuity being a mild term to apply to it. What money wasn’t taken in at the gates or by the shell games was usually cleaned up the ‘gooseberry crowd’ that followed the circus and while the people were watching the performance, raided the houses. Sometimes the ‘gooseberry’ bunch was in cahoots with the show and sometimes they were not, but they usually made a cleaning. Some small towns were literally wiped clean by the circus bunch.”

Locals, however, often lashed out after discovering their town had been “wiped clean.” Underwood recalled, “When they got a chance to get their breath and compare notes, they usually came down on the circus with blood in their eyes. The ‘fakirs’ had moved on to greener pastures by this time and were ready to work the next town. The circus hands had to bear the brunt of the storm. One experienced stake driver with the heavy, banded circus stake, could usually clean twelve or fifteen ‘rubes’ but just the same there was much bloodshed and cracked heads.”

He also somberly told the story of a young Kansan who had just sold a load of corn for a large sum of money, possibly as much as $200, and decided to bet it all on a shell game. He lost. The shell game operator, scared the crowd was going to attack him, fled. The young farmer chased him into a tent where the man cracked the rube over the head with a club. Underwood claimed, “It was one of the most cruel sights I have ever witnessed, but those were hard days in the circus business.”

Circuses are few and far between these days, but undoubtedly the big top once thrilled crowds all across the country, and Joplin was no exception.

Sources: Joplin Globe, Joplin News Herald, Livingston’s History of Jasper County, Bale Milling Odyssey by Judy Hurdle, Missouri Death Certificate Database 1910-1959, Judy Hurdle private collection