Although the Spook Light is not located within the city limits of Joplin, it’s worth recounting some of the folklore and first-hand accounts of the strange phenomenon. Even though the Spook Light no longer draws in hundreds of cars during the summer, ask any native of the Four States about the Spook Light and they’ll probably have a story, or can share a story that they heard from one of their friends. Much of the recent press surrounding the Spook Light has been rehashed from earlier accounts, so we will focus our attention to early published accounts.

In the late summer of 1934, Clara E. Gordon and her family were on their way home to St. Louis after visiting the Grand Canyon and Mesa Verde when they stopped at “Idle-a-While Camp” just off Route 66 in Carterville. The proprietor suggested they go out and see the “Indian Lights” south of Joplin. The Gordons, the camp owner, and two guides set out for the Spook Light. Right after they got out of the car, “an orange-colored light appeared in the center of the road about three hundred feet beyond.” They walked toward the light, but it disappeared. The group jumped back in their car and sped toward the area where they saw the light, but did not find it. “We remained at the place two hours,” Gordon recalled, “and during that time the lights came at intervals of from four to seven minutes and remained shining for that long, then vanished or faded away regularly.” She noted that the light was “never a white light or natural color but usually of orange or a greenish hue.” Upon her return to St. Louis, she tried to research the phenomenon for an answer, but failed to say if she believed in one theory or another.

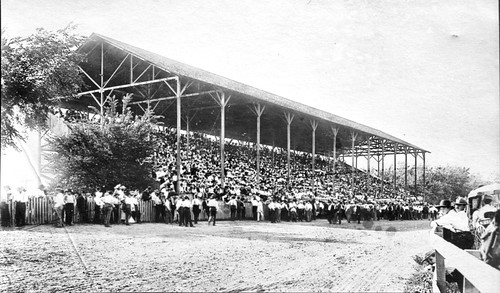

In January 1936, reporter A.B. McDonald of the Kansas City Star published his own account, “The Mystery Light of the Ozarks on ‘The Devil’s Promenade.’” McDonald and a handful of locals from Neosho drove out to the area to search for the source of the light. He interviewed a farmer named Tracey who claimed, “I’ve been studying it for four years and the more I watch and study it, the more puzzled I am about it.” Thousands of cars, Tracey said, had passed his home in search of the light. During the summer, he observed, there were sometimes one hundred cars parked, waiting. On a normal night, there were usually 15 to 20 cars parked along the road.

McDonald and the group set out on the foot after parking their cars. One young woman exclaimed, “Heavenly day!” as she saw the spook light for the first time. McDonald observed the phenomenon and noted that it reminded him of the glow “I had often seen when driving along a road at night where there was a hill ahead and a car behind the hill was approaching toward its summit, the glow from its headlights

illuminating the air above the summit several moments before they cameinto full view.” Margaret Tuller, a Newton County home economics demonstration agent who accompanied McDonald, was disappointed the light did not split into two separate lights. According to Tuller, who professed she had spent hours studying the phenomenon, “The two lights are always one straight above the other. Sometimes they remain apart until both disappear, and sometimes they merge together again into one light.”

On a tip from the Joplin Globe, McDonald visited James Nutz, a Joplin mechanic, and Raleigh Carter, the owner of an engraving shop. The two men believed they had solved the mystery. Nutz and Carter asserted the light was coming from a light on top of a gravel pile near a zinc mine just outside of Quapaw, Oklahoma. When the reporter asked how fixed lights on top of a gravel pile could move, the men said that the light, in their opinion, did not move at all, arguing “It simply appears to move as you look at it through the foliage of the trees between you and it, and the same moving of the foliage of the trees

makes it seem to disappear and return again.”

The intrepid reporter found the most convincing argument came from Logan Smith, foreman of the composing room at the Neosho Times, who argued the lights were the results of cars traveling along Route 66. When asked about seeing two lights, Smith pointed out that, “[If] you stand in a road and look at a car coming anywhere from two to five miles away and you will not see two lights, you will see only one. At that distance, the two lights are merged into one.”

When McDonald asked Smith about the stories regarding the Spook Light that pre-dated the invention of the automobile, Smith responded, “Those stories all remind me of the story of revivalist Sam Jones and the frogs. Or in that other fable of the mouse that went in to the ear of a person came out his mouth a full grown elephant.” In 1946, the Kansas City Star published an article by Charles W. Graham. Graham, curious about the Spook Light after reading a first-hand account by C. Paul Spidell of Baxter Springs, Kansas, visited the region to conduct his own investigation. Graham contacted Colonel Dennis E. McCunniff at Camp Crowder in Neosho, and obtained the assistance of Major Thomas E. Sheard, the post signal officer. After a series of on-the-ground tests and aerial flights, Graham, Sheard, and others involved in the investigation were satisfied that the Spook Light was nothing more than car lights.

In his 1947 book, Ozark Superstitions, folklorist Vance Randolph touched briefly on the Spook Light. He mentioned Logan Smith of Neosho being of the belief that the lights were those “of automobiles driving east on Highway 66.” Newton County agricultural agent F.N. Darnell “and a group of surveyors from Joplin, also incline to the view that cars on the distant highway are responsible for the mysterious lights.” Yet Fred C. Reynolds pointed out his grandfather, “a pioneer doctor at Baxter, Kansas” had seen the lights “long before there was any such thing as a motor car.”

Another prominent Ozark folklorist, Otto Ernest Rayburn, published Ronald Ray Bogue’s article about the Spook Light in an issue of his magazine, Ozark Guide. He recounted a few of the popular legends surrounding the origin of the Spook Light, including the story about the ill-fated Native American lovers and another about an old settler who lopped off his wife’s head in a drunken fit. Unable to find her head, he disappeared, and is thought to roam the countryside with a lantern looking for it. Rayburn recounted a story from a woman who claimed to have gone with her husband and another couple to look for the Spook Light. After arriving at Spook Light road, she said they got out of the car and sat on the fender, waiting. After thirty minutes, “There appeared a soft white light in the sky about one hundred yards down the road. Slowly it grew brighter and closer, zigzagging across the road. Finally it got so close and bright that my girl companion and I scurried back into the car. Although it was summer, we rolled up the windows and locked the doors.”

The women watched as the light came toward their husbands. The men tried to get into the car, but finding that their wives had locked the doors, scrambled to get under the rear of the car. The light “sat down on the radiator of the car and its brilliance was dazzling. My friend cried and hid on the floor of the — I sat hypnotized by the light, trembling with fear, yet unable to move.” After a period of time, the light blinked, and then disappeared. The woman declared, “I haven’t been back to see spook light since then, and I’m not going in the future, either.”

Old-timer Bill Mizer boasted, “I’ve been around here since 1886, and I have heard all the stories, but this story about the light, and the first time it was seen was in 1903.” Mizer went on to say that a widow first noticed the light and thought it was someone trying to run her off of her property. A group of young men decided to find out what was happening. Mizer, along with Jake Leach, Edgar Zirkle, W.L. Buzzard,

Hiram Elliott, and John Ventle, and “maybe others” set out to investigate. Thinking it was phosphorous rising from a clump of cattails on the widow’s property, the group settled in nearby to watch.“We didn’t have long to wait before we saw the thing that had the widow frightened,” Mizer recounted, “The first time I saw the light, my hair raised several inches from my scalp, and I had a hard time keeping my hat on my head.” The light floated around, but when the wind came up, it disappeared. Shaken, the young men returned the next night, and observed the same thing.

Mizer noted, “After a month or so, the light stopped reappearing with regularity, and we had almost forgotten about our experience, but early in 1905 reports had started coming in again about the light.” He still was not sure what the source of the light was, noting, “I tell you — when you’re sitting out there in the dark, and this ball of light floats around for a while, and disappears, you begin to wonder.”

In a tiny pamphlet entitled, “Ghost Lights,” Garland “Spooky” Middleton, the second owner of the Spook Light Museum, published statements from individuals about the Spook Lights. Louise Graham of Galena, Kansas, said, “While coming home from a school carnival at Quapaw, Oklahoma, we got the thrill of our lives. The light had evidently grown tired and weary and decided to do a little hitch-hiking on our bus. The light perched on the rear window as though trying to get in the bus. We were scared half to death — women screaming and all. The light was so bright it temporarily blinded the bus driver and he had to stop the bus. Just as we stopped, the light went away. I’ll never forget that bus ride.”

Leonard Stoner of Quapaw, Oklahoma, said, “I’ve lived around Quapaw for 61 years. I’ve seen a number of teams investigating the source of the ‘Ghost Light,’ but none of them have ever found out what it is. I was here before there were any cars in this district and the ‘Ghost Light’ was there then.” Frank Allen, Jr., an African American resident of Joplin, proclaimed, “I ain’t been [to see the Spook Light] and I ain’t going and you can be sure they won’t be any segregation problems on that road.”

One humorous account from an anonymous resident of Tulsa recounted, “My parents reside in Neosho. While visiting them we drive out to see the spook light quite often. Old settlers down here say their ‘night life’ falls into two categories — Those who have kidney trouble and those who go to see the spook light. One old widow told about having to move to Neosho from Spooksville. She said, ‘The light makes me

nervous and irregular.’ I think she must have meant ‘irritable.’”

If you have a Spook Light story, we’d like to hear it!