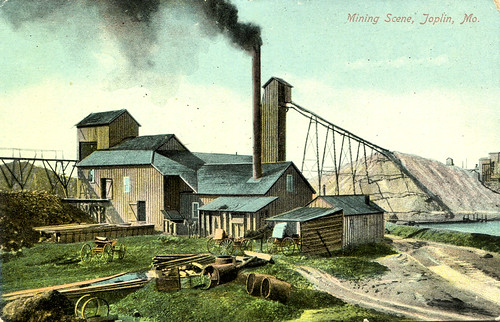

From time to time, we like to point out resources for Joplin’s and Southwest Missouri’s history. For those of you who haven’t glanced at our links page, you likely haven’t noticed the link to Missouri Digital Heritage. At that site is located the repository of the Joplin Public Library digital postcard collection which was used to great effect by Patrick McPheron in his Joplin video that we posted a couple days ago. However, that’s not all that you can find at Missouri Digital Heritage worth looking at with concern to Joplin. Another fantastic resource is Riches from the Earth.

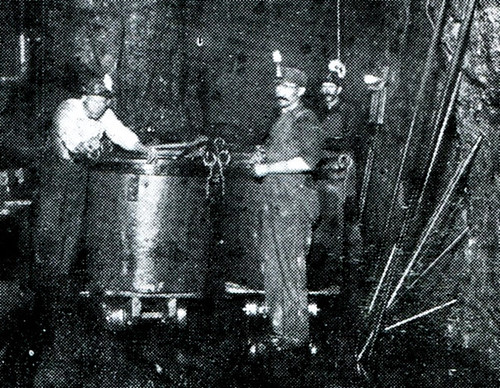

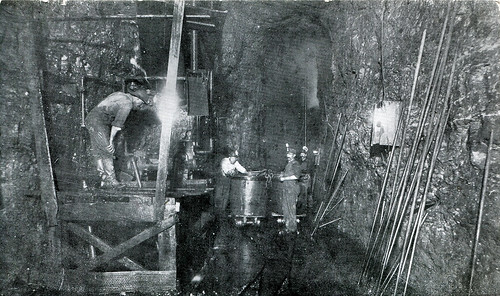

Riches from the Earth describes its purpose as, “Riches of the Earth provides a basic introduction to the geological and industrial heritage of the Tri-State Mineral District. This district encompasses southwest Missouri, southeast Kansas, and northeast Oklahoma and was one of the United States’ richest mineral districts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” More importantly, it’s focused entirely on Jasper County, the “heart of the Tri-State Mineral District.” What follows is 261 images of mining, from mines to miners, to even a few mules.

The project is a collaboration between the Powers Museum, Missouri Southern’s Spiva Library Archives and Special Collections, the Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Rolla at the Missouri University of Science and Technology (U of Missouri – Rolla), and the Joplin Museum Complex. It should be noted that if you have hopes of taking a peek at any of the Joplin Museum Complex’s photograph collection, this will be your only bet outside of buying one of the couple books the museum has deigned to publish periodically. At this time, the photograph collection is generally off limits to the inquiring public (and in the process – Joplinites are cut off from freely accessing the best photographic and visual depiction of the city’s past).

Photograph access aside, Riches From the Earth is a good source for historic images of Joplin’s and Jasper County’s mining past. It does suffer some from the slightly clunky interface of Missouri Digital Heritage website, but it’s a small price to pay for a glimpse into the past.

Note: All images are from Historic Joplin’s own collection.