On Friday, July 30, the Joplin Globe ran an article noting that the renovation of the Spanish villa-style mansion that formed the nucleus of Joplin Community College’s expansion was nearly complete. The 90 year old manor, which has had many roles, will be the new home of the alumni association. Tying the home into Joplin’s history, besides it’s role with Missouri Southern State University, is the fact that it was built by a wealthy mine owner. As the last few decades have not been kind to the marvelous architectural feats funded by the mines of Southwest Missouri, it’s great to see one of them given a new lease on life.

Roy Always Gets His Man

After stealing coal from the House of Lords, fourteen-year-old Roy Smith began serving a four month sentence at the Joplin city jail. What was notable about the young African American’s stint at the city jail was that no one filed a complaint against him and he was not tried for theft in police court. Instead, Smith’s guilty conscience led him to serve a self-imposed sentence. Deputy Chief Frank Sowder remarked it was the, “strangest case on record.”

Roy’s friends tried to convince him to “shake” the police after a few days, but he stubbornly stayed at the jail. He busied himself sweeping the police courtroom, building fires in the station in the morning, and running errands for the officers. When asked, Roy told a reporter that he planned to follow the law and serve his sentence.

Officers who may have thought Roy was good at keeping the jail tidy found out that he had even more to offer. Two small paperboys arrived at the jail and reported they had been assaulted by two black boys who pelted them with rocks and struck them with their firsts. Roy, whom officers had nicknamed “Cooney,” listened to their story. He then volunteered that he could identify and find the two black boys. Chief McManamy granted Roy permission to go apprehend the suspects, laughing at the boy as he headed out the jail. But the chief found himself surprised when ten minutes later he heard a “terrible commotion” in front of the jail. Looking outside, McManamy saw Roy dragging two “much larger negro lads by the coat collars.”

Roy proudly announced, “Here they are.” He then proceeded to drag the two boys into the jail. According to Roy, he used the power of verbal and physical persuasion to get the two boys to accompany him to the jail. Roy, who had observed officers over the last few weeks, took every precaution: He searched his prisoners before he handed them off to Chief McManamy, who performed the duties of desk sergeant. A few minutes later, Roy announced he “had scared them into making a complete confession.”

Roy formed a close friendship with Bosco Busick, the assistant deputy poundmaster and patrol wagon driver. The two of them would fall asleep in the big cushy armchairs in the jail at night after talking for hours. Despite fleeting moments of relaxation, Roy continued to serve as Joplin’s junior Sherlock Holmes.

A few weeks later, Roy was called to service once more. When the police needed to question a young African American girl about the whereabouts of some suspected criminals, the officers brought her to the station, put her in the sweatbox, and pressed her for information for over thirty minutes. She professed ignorance. Roy, who had been out buying tobacco for one of the officers, arrived and observed the interrogation. He winked at Night Captain Loughlin and began to talk to the girl. Soon he had obtained the information the officers sought. His task finished, Roy grabbed a broom and started sweeping the jail, which was now decorated with pictures and cartoons he had drawn for the officers.

Like many of Joplin’s other characters, we’re not sure what happened to Roy Smith, but it’s clear he made quite the impression on the Joplin police. One can only hope he stayed on the straight and narrow.

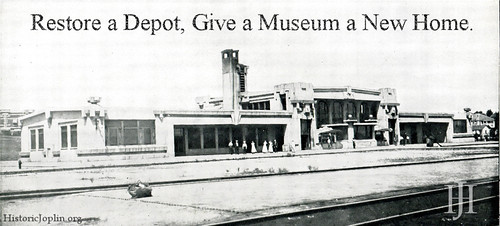

Got Any Photos of the Union Depot?

Earlier this week, the Joplin Globe ran a story concerning a request for photographs of the Union Depot. As part of the growing movement to renovate the Union Depot, architect Chad Greer has requested of the public any and all photos of the Union Depot’s interior. A visit to the Depot will reveal that there is very little left in the old train station at the moment, much of it stripped during the previous attempt at renovation. For links to some interior photographs and a video walk through of the interior, see this previous post.

In the realm of restoration, the goal is to achieve the closest resemblance to the past as possible. Achieving that aim can also be expensive, hence the need to know exactly what you’re trying to accomplish. For those who might have interior shots of the Union Depot, see the first link for contact information with Mr. Greer. Importantly, you don’t have to relinquish those family photographs, either, Greer and his associates can make a copy of your photograph and let you keep the original. An additional aspect of this request is to build up a photographic archive as a historic collection, something we naturally applaud.

A Rainstorm Floods Joplin – The Flood of 1916

The last few weeks have been scorching hot in southwest Missouri. In 1916, however, a sudden cloudburst wreaked havoc upon Joplin that seems almost unreal.

A “severe electrical storm” began at 10:30 at night with a host of giant storm clouds that hovered over the city until they burst and flooded the city below.

The deluge began with 5 and ¾ inches of rain during the night, followed by 5 and ½ inches within a two hour period in the morning. The rain was accompanied by a savage hailstorm that forced pedestrians to run for shelter. The downpour continued throughout the afternoon and in just a few minutes more than an inch of rain had fallen. Total rainfall was estimated at 6 9/10 to 7 inches. Long time Joplin residents remarked that it was the most severe storm the city had experienced.

According to C.W. Glover of 216 North Wall Street, the rainstorm was nothing compared to one that ravaged Joplin in July, 1875. According to Glover, it rained for three days and three nights. Joplin Creek, which divided East Joplin from West Joplin, became a raging torrent that no one dared cross. Professor William Hartman, a musician, and his wife were drowned, and several others were almost lost when seeking shelter or attempting to rescue those endangered by the flood waters. Joplin’s horse drawn trolley was unable to travel to Baxter Springs due to the washed out roads and streets.

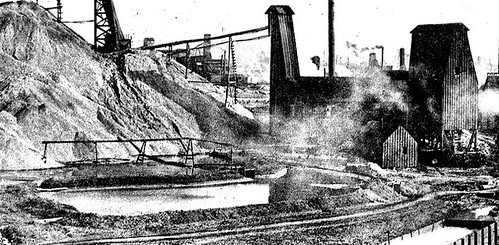

The 1916 storm was so sudden that it caught many people off guard. John Moore, Edward Poe, and Peter Adamson, miners working in the Coralbut (formerly the Quaker) mine west of Chitwood, were drowned when rainwater swept down into the mine at such a furious rate that they were unable to escape in time. Unfortunately for the three miners, the water had pooled at the top of the mine behind piles of debris that had formed an old mine pond when the debris gave way and a torrent of water flooded the mine shaft.

Altogether there were twelve men in the mine and they scrambled on top of some boulders as the water began to rise. The hoisterman at the surface lowered a tub to rescue them, but the water was so high and the current so strong that the men were reluctant to jump across the water into the tub. Nine of the miners were able to escape before the water overtook them. Moore, Poe, and Adamson said they could not swim and thought they would be safe on top of the boulders. It was not before long, though, that the hoisterman heard them call for help. One of them yelled, “For God’s sake, get a boat before we drown!” It was too late. They were unwilling to jump to the tub across the raging water and were drowned despite the efforts of their fellow miners to go down in the tub and try to reach them. The bodies of three men were not immediately located by rescuers.

One of the miners who escaped, Roy Clark, had been a sailor on a tramp steam freighter out of Queenstown. He declared after his harrowing experience that he was “through with mining.” Clark, who claimed he had developed strong swimming skills as a sailor, said he would not have dared to swim through the water that had flooded the mine. Another miner who had been in the mine, C.E. Evans, said he had warned his fellow workers about the storm. He said he had picked up hailstones as big as his thumb that had fallen into the mine and knew that trouble was not far off. By the time they saw the water pour in and ran for the boulders, he said, the water was up to their waists and rising. The tub, he said, was slow in coming. Evans’s fellow miner, Lowery, was standing on a boulder with water up to his chin when he was able to get to the tub.

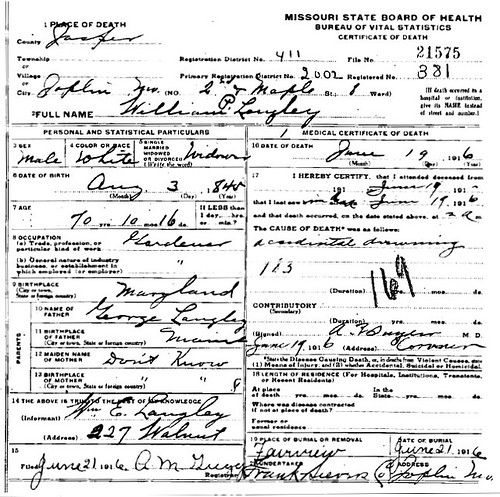

Even those who were in the safety of their own home were not shielded from the storm. William Langley, a 70 year old gardener, drowned in his home at Second and Ozark streets when it was submerged by water due to the home being situated next to a steep draw that funneled water down into the house.

When rescuers broke into Langley’s home, they found that the water had been only six inches from the ceiling. Some families in Chitwood sought refuge on top of their homes as the water began to rise, while others remained in storm shelters, still afraid to venture out due to the lightning and hail of the past few hours.

Mines suffered damage. The Grace Mine mill, located a mile north of Chitwood, and the Longfellow school building were both hit by lightning. Mine owner W.H. Gross of 318 West Eighth Street estimated damages at $15,000. Several other mine buildings were struck by lightning but did not burn. Many more were filled with water and required large pumps to remove the water. Total damages for mines across the Joplin area were estimated at $200,000.

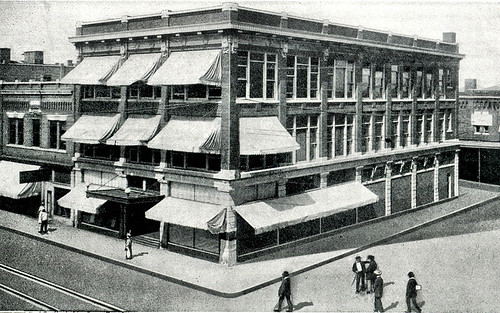

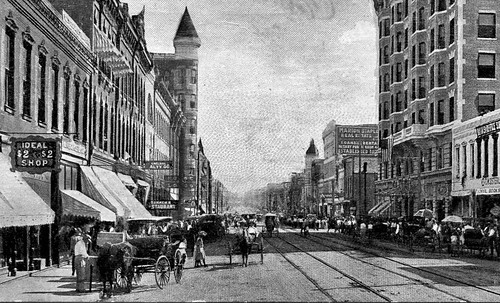

The storm of 1916 caused severe damage to downtown Joplin. Main Street from Fourth to Sixth streets was a “white-capped torrent for more than two hours” with a depth of two to five feet deep in some places. Businesses along this section of downtown reported losses of $100,000. Fleischaker Dry Goods, Christman’s, and Ramsay’s suffered severe flood damage. Ramsay’s lost all of the merchandise stored in the building’s basement which was filled with six feet of water at one point. Christman’s reported $10,000 in losses. Merchandise located on the lower shelves of the stores was thoroughly soaked.

One odd occurrence was when a bolt of lightning struck two wax figures in the Menard Store located at 423 Main Street. One of the figures was completely melted while the other was only scorched on the arm.

At the Commercial billiard parlor at 521 Main Street, seven billiards tables were ruined. Not far down the street the Priscilla Dress Shop at 513 Main lost several expensive Parisian gowns valued at $3,000, artwork estimated to be worth $2,000, and $300 of electrical fixtures destroyed.

It seemed as if no business escaped the wrath of the storm. The Farrar-Stephens Auto Tire Company at 520 Joplin Street reported damages of $5,000 while Kresge 5 and 10 Store lost merchandise valued at $5,000. The Joplin Pittsburg Railway Company suffered $2,500 in losses. The Burke Cigar and Candy Store and the Electric Theater building only had $2,000 in damages. Even the vaunted House of Lords suffered $500 of damage.

Joplin’s Hello Girls found that the storm caused $10,000 worth of losses. Nearly 4,000 telephones were out of service after the rain stopped, almost half of Joplin’s total number of phones. Poles were down, wires severed, circuits dead, and fuses blown all over town. Long distance lines, however, received very little damage. Phone company officials considered it a miracle.

Bridges and roads were hit hard. At least two large bridges were washed out, including the Joplin and Pittsburg Railway Company bridge over Turkey Creek. Track was twisted and torn up and down the line. A “masonry bridge over Turkey Creek at Range Line” was supposed to have been totaled at a cost of $1,000. Trains from the Kansas City Southern, Frisco, and Missouri & North Arkansas railroads were unable to roll into Joplin.

One enterprising young man captured a bathtub that floated out of a plumbing shop and used it as a canoe to paddle through downtown. Others joined him in boats and canoes (undoubtedly those who enjoyed fishing on the Spring River) while others just waded into the torrential streams of water. Barrels, boards, and all sorts of other debris clogged the streets and alleys. Citizens worked to grab the debris before it smashed out store windows and created more damage.

Giant potholes waited to twist ankles for those who dared to walk through the muddy water. Motorists were asked by city officials to drive slowly lest they hit a pothole and total their cars. Sidewalks were washed out as were sections of wood block pavement from Main Street to the Frisco rail tracks. City parks were ravaged. A sewer main burst at the North Main street viaduct and created a health hazard.

Joplin was battered, but not broken. In time, debris was removed, mud swept away, and the ravages of nature relegated to memory.

Want Ads from 1915

Some things change; others stay the same. A look at a sampling of ads from an issue of the 1915 Joplin Globe illustrates this.

Livestock For Sale:

For Sale — Good single horse and express wagon. Joplin Wholesale Grocery.

Work Horse for sale cheap. 2409 Bird.

Fresh cow and calf for sale. 1107 Bird.

Team of mules for sale; weight about 1,000 each. 1116 West A.

Team, harness, wagon, $100. C. Rouse, one-fourth mile west Central City. Phone 8011-J2.

Automobiles, Motorcycles:

Twin-cylinder Harley Davidson motorcycle, 1914 model, complete, run less than 40 miles. Box F-16, care Globe.

For Sale — 1913 model 50 T. Cole automobile, electric lights and self-starter, new tires; car in fine condition. Address J.J. Scheurich, Joplin, Mo. Residence phone 3655.

For Sale — Cheap; Saxon roadster, in good running order. D.C. Smith, Radley, Kan.

Miscellaneous for Sale:

One pair of fine diamond ear screws, weight 1 ½ carat, at a bargain. Dameron, 1412 Main.

New White sewing machine. See L. John, 701 Pearl Street, or phone 1962-J.

For Sale — Player piano, nearly new; perfect condition; original cost $700, will sell for $350 cash or terms.

Coal — Best lump coal, delivered, $3.95, weights guaranteed. Phone 422 or 1647, Pittsburg, KS.

A good Mills slot machine; good working order. Address Edwards , 108 North Kansas, Columbus, Kan.

For sale cheap if taken immediately. $200 Victor Victrola, perfect condition. Box F-1, Globe.

Beautiful $25 blue serge coat, size 86, $5. Call 3822-R.

Hand-made spring wagon at a bargain. Pearl Brothers.

New Steinway Baby Grand piano. Box E-10 care of the Globe.

National cash register in fine condition. 814 Moffet.

Bargain is satisfaction. Vola Vita hair tonic.

Good bicycle for sale. 1922 Carter.

Help Wanted – Female:

Wanted – At once, a lady bushler at 421 Main.

Wanted – Dining room girl. Turner Hotel

Wanted – Woman that wants to work. Great Northern Hotel.

Wanted – Girl for general housework. Mrs. J.T. Hughes, 810 Virginia Avenue.

Government jobs for women; $70 a month; list positions now obtainable, free; write immediately. Franklin Institute, Dept. 653, Rochester, New York.

Wanted – Mending. Call 511 Picher.

Houses for Rent

Modern sleeping rooms. 413 Wall.

Seven Room modern house. 2218 Joplin Street.

For rent — 4 room cottage. Call 1402 Pearl.

Modern 5-room apartment, all conveniences. 421 West A.

For rent — 4 room modern house, large barn. 2214 Pearl.

Lost, Strayed, or Stolen:

Lost — Fresh Jersey cow; liberal reward for return to 728 May.

Strayed — Five calves, black Jersey, two yellow heifers, two bull calves. Phone 1390.

Lost — Sealskin wallet containing pictures and papers; suitable reward for return to B.B. Standard, King’s Book Store.

Coat taken from Keyhill’s by mistake has been returned there; party getting other one, containing keys, please exchange.

Lost — Bunch of about 12 keys on 2 rings, connected, between gas office and Villa Heights. Finder please return to gas office.

Mining Machinery for Sale

Small tailing mill cheap. 206 Miners Bank bldg.

Keystone No. 5 drill for sale. $1,150, special terms. Address R.H. Barratt, 316 Miners Bank bldg. Phone 3071.

For sale — 25 h.p. Witte gasoline hoist in good condition, big bargain. Pittsburg Boiler Works.

For Sale — 25 and 36 h.p. upright boilers, complete, with all trimmings. Liberty Bell Mining Co., West Seventh Street. Phone 848.

Poultry, Eggs, Etc.

Want to exchange Crystal White Orpington cockerel for baby chicks. 715 Byers.

Hibbard’s White Rocks for sale. Cheap: stock, eggs, must have room for young stock. Hibbard, Oronogo, Mo.

For sale — Barred Rock hens, cockerels. Mrs. Adkins, three blocks south Parr Hill school.

Barred Plymouth Rocks, Buff Plymouth Rocks, Fawn Indian Runner duck eggs for hatching. 514 Picher.

Fancy single-comb White Leghorn eggs for hatching. J.C. Wright, East Main, Carterville.

Wanted to Buy

Wanted — To buy moving-picture machine. Address F-9, care of the Globe.

Wanted — 150 or 160 h.p. Bessemer gas engine. Call 3480-J.

Wanted — A geared hoister, with or without engine. Phone 3391.

John Artwood – Survivor of the Seas

As the sinking of the Titanic flashed across headlines over America, one Joplin miner recalled his own near death experience at sea.

In early April, 1912 the headlines of all three Joplin newspapers were devoted to the tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic. The Joplin Morning Tribune featured an interview with John Artwood, a Joplin miner, who almost suffered a similar fate.

Before arriving in Joplin, Artwood spent ten years at sea. The last ship he worked on was the Keyton, a “fishing smack,” that boasted a crew of twenty-one men. The Keyton was four hundred miles off the coast of Newfoundland when it collided with a “derelict” and sank. Of the twenty-one crew members, only five survived.

As Artwood recalled, he and four of his fellow crew members scrambled into a raft and spent the next twenty-eight hours adrift at sea at the mercy of the open sea and “treacherous currents.”

According to the former sailor, “So far as the sinking part of it was concerned our suspense didn’t last any four hours because the Keyton went down in forty minutes after she struck the derelict and not more than two minutes before five of us succeeded in getting away from her on a raft. Several other members of the crew made a desperate attempt to get on the raft, but it was in vain and we witnessed the horrible and never-to-be-forgotten spectacle of seeing some fifteen brave men drown like so many rats.”

When the Morning Tribune reporter asked Artwood about his experience, he took a minute to reflect upon what had happened to him before he confessed, “Well, your first feeling is one of fright, but this is quickly succeeded by one of determination to help your comrades as well as yourself to escape an awful fate.” Artwood continued, “Your body becomes numb as our mind becomes doubly active and you have little feeling in a physical sense during the excitement. Your flesh may be torn on an arm as a result of your desperate efforts to ear up decks to get timber for you raft but you will never feel the slightest pain until you are relieved by the realization that you have been saved, that you have been snatched from the jaws of death.”

Artwood felt his experience was similar to that of the Titanic survivors. “Yet, in a way it was worse,” he explained, “because on the small craft we could feel her sink very rapidly while on the mammoth liner there were many who did not know she was sinking for some time, so slow was the movement downward.” In his case, “When the Keyton went down she displayed little resisting power for she had not the semblance of such bulkheads as doubtless tended to prolong the Titanic’s sinking. Every man on board could feel her settling from the minute she struck the downward with about the speed of a slow-moving freight elevator, which seems speedy to one out on the sea hundreds of miles away from land.”

His freight at his situation, Artwood managed to mash a finger and had the flesh on his right arm cut to the bone in an effort to carry some heavy timbers to hastily build raft. He “never felt one bit of pain from either injury until several hours after they were inflicted. There was no part of my mind at liberty to think about physical pain, but there was a mental anguish instead and this was ten thousand times worse, although it tended to urge me on to do things I never knew I was capable of. Every second it seemed as though I had lived a whole day of terrible anxieties and a minute seemed like weeks.” After twenty-eight hours, a fishing “smack” boat arrived on the scene to rescue the Keyton’s survivors.

After his rescue, Artwood said he “got to the United States as quickly as he could and he has never been on water since” and arrived in Joplin sometime in 1910 when he became a miner. Perhaps Artwood may not have realized it at the time, but he had traded one dangerous vocation for another as our previous post “Death in the Mines” illustrates.

Source: Joplin Morning Tribune

Cocaine Jimmy

When one thinks of cocaine, they may think of the 1980s, Nancy Reagan, and the War on Drugs. Cocaine, however, was in Joplin long before tv commercials showed eggs frying in a skillet while a voice somberly intoned, “This is your brain…This is your brain on drugs.”

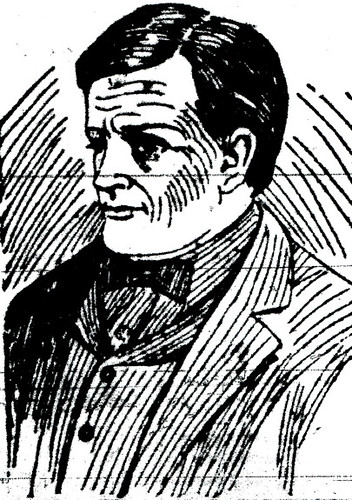

Perhaps the most infamous cocaine user in Joplin was Daniel “Cocaine Jimmy” Shannon. One day, Shannon was found passed out behind the House of Lords by members of the Joplin police department in what one physician thought was “the last stage of drug poisoning.” He was taken to the city jail to spend the night and was transferred the next day to the Jasper County Poor Farm in Carthage. One doctor remarked, “He can hardly survive this attack, and at the poor farm the drug will be taken away from him altogether. He is too far gone to be benefited by that treatment, and I am inclined to think that his days are numbered.”

Cocaine Jimmy granted an interview following his near fatal drug overdose. He told a reporter, “I have been a drug fiend for 18 years. The average life of the cocaine or morphine fiend is five years. I think the Lord must have let me live this long in order that I may be cured and live to do some good in this world.”

Jimmy, it turned out, had not always lived on the edge. As a young man, he attended the Chester Military Academy in Chester, Pennsylvania, and then attended a music conservatory in Philadelphia. This fact, the reporter noted, “many of the people of Joplin are ready to believe, for they have heard him play at the music stores. When under the influence of the deadly drug to which he is addicted and at just the right state, he has shown himself many times to be a brilliant performer upon the piano.”

According to Jimmy, his father was wealthy, and even played host to President James Buchanan at the family home in Pennsylvania. But after becoming addicted to cocaine, Jimmy left behind a career as a lawyer, and instead spent his time working on and off as a janitor at the Sergeant building at the corner of Fifth and Main. The reporter observed that Jimmy talked little of his past. One lawyer who doubted Jimmy’s former occupation as a lawyer was stunned when Jimmy began quoting sections from Blackstone’s law almost verbatim. In manners, he was always extraordinarily polite, always thanking anyone who helped him and making sure to say hello to others.

The paper remarked, “Those who knew Shannon in his brighter moments and could see what the man had been and what he might have been, will hope ‘Cocaine Jimmy’ himself that after all the Lord will see to it that he is cured; that he may live to accomplish something in this world.”

A few years later, Jimmy was still alive, and granted another interview to a Joplin reporter. Jimmy was described as a, “little, old appearing man, with a wrinkled face and a tinge of gray in his air, and although he is only 40 years old, his beard, when not closely shaven, is as white as snow.” His cheeks were hollow and there were “great hollows under his eyes.”

Although the moniker “Cocaine” was understandable, there was no explanation as to why he was called “Jimmy” when his given name was Daniel. His friends had pooled enough money to put Jimmy through an unspecified treatment program which seemed to be working until he suffered a painful bout of inflammatory rheumatism and relapsed.

Jimmy told the reporter he first used cocaine while receiving medical treatment at a hospital in the Dakotas. He used small amounts at first so that it was not readily apparent that he was using the drug. He “began the use of cocaine by dipping the needle in it when I wanted to take a ‘shot’ of morphine in order to keep the needle from hurting me. The desire for cocaine grew on me until I now use the two drugs equally mixed.”

He did not like practicing law, so his father set Jimmy up in the musical instrument business. He enjoyed teaching music and soon took “one of the prettiest little women there was” as his wife. Jimmy’s love of cocaine, however, was stronger and he began to abuse cocaine at a greater rate. He abandoned teaching, left his wife, and took all of his money out of the bank. Jimmy proclaimed, “There is not an hour in the day when I do not wish I could be cured of the terrible habit and straighten up and be a man.”

Jimmy told the reporter, “I cannot understand why any young man or young woman will begin the use of cocaine or morphine. My body from head to foot is a complete mass of scars which have been made by the hypodermic syringe.” The craving for the drug was so bad, he said, “there is nothing short of murder that will prevent him from getting it.” On average, he used fifty to seventy-five cents worth of cocaine per day. He then gave a lengthy description of the hellish existence of a cocaine user, described the multiple ways one could use the drug, and then sadly said, “My one ambition is to get enough money to take the cure and if I can get thoroughly cured of the habit I feel that I would never again touch a drop either of cocaine or morphine.”

Sadly, Daniel “Cocaine Jimmy” Shannon did not live much longer. He was discovered unconscious behind Ferguson’s Saloon by members of the Joplin Police Department who carried him to the Joplin City Jail. He was remembered for his daily plea of, “Give me a nickel.” Although he “was a well known character upon the streets, he never figured conspicuously in police court, and was but seldom arrested.” When arrested, it was for begging or for passing out on the street. In his obituary, it was noted that he “was an expert pianist and during his career in Joplin frequently was employed by proprietors of beer gardens and north resorts as a pianist.” Despite three desperate attempts to be cured of his habit, Jimmy died, and his body was held at the Joplin Undertaking Company until family members claimed the body. Where he was laid to rest is unknown, but one wonders if his ghost still lingers on the streets of Joplin, still looking for one last fix.

Source: Joplin Newspapers

Rochester Kate

In the winter of 1907, Joplin received a visit from “Rochester Kate” a female hobo who ran away from home sometime in the late 1880s at the tender age of twelve. She claimed to have visited “in every state and territory in the union and made two trips through Europe, paying her way in the steerage once and hiding in the hold the second time.” According to Kate, her fare “across the Atlantic in the steerage was the only money she ever paid for transportation in her life.”

The world traveler, who was in her early thirties, arrived in Joplin via a car on the Kansas City Southern freight train. As the train passed the Frisco crossing she jumped off and walked into Joplin through the Frisco yards. She must have been an object of curiosity as the Globe noted she “despises dresses and wears a pair of corduroy trousers.” When interviewed by a Globe reporter, she was wearing a “very heavy sweater of good quality” and a coat. The only giveaway as to her gender was her long hair of which she was “very proud.”

Rochester Kate told the reporter, “I’ve been moochin’ since I was a kid. One day I got mad at Ma and got on a freight that was standing on a side track back of our shack. We hadn’t gone far when the brakey [hobo slang for brakeman] spotted me and put me off at the next stop. A guy let me ride on a wagon with him back home and I got a beating.”

But wanderlust was in Kate’s blood and she soon took to the rails again. She remembered, “I kept running off after that and when I was about 15, I guess, I lined out one day and didn’t come back. I couldn’t stand staying around a place very long after I lined out the first time. I mooched up to Buffalo and got a job in a factory and saved up a little and mooched it to Chicago on the blind most of the way, and I been a going since.”

The reporter observed, “Aside from the professional slang words picked up on the road, Rochester Kate does not use the rough language that would be expected from such a life, nor is her appearance as rough as would be thought.”

Kate would not tell the reporter how long she planned to stay in Joplin or where she was headed next, saying that “she did not care to have the police know too much about her movements, as she had spent too many days in jail for vagrancy.”

Source: Joplin Globe, 1907

Urban Renewal circa 1907

Downtown Joplin has seen its share of buildings come and go over the years. One might think that urban renewal, which ravaged much of the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, is to blame. But as much as urban renewal makes us howl here at Historic Joplin, it’s not always at fault. Back in 1907, it was announced that the Peter Schnur residence, one of Joplin’s oldest surviving buildings, would be demolished.

The Schnur residence was built in 1871 by Peter Schnur, one of the first residents of Joplin, and founder of the Joplin Evening News. When he was appointed postmaster of Joplin, Schnur sold the newspaper. According to Joel Livingston’s history of Jasper County, Mr. Schnur died in 1907 “after marching in a parade.”

The house originally consisted of two small rooms. In subsequent years the house was added on to and received an interior coat of plaster. It reportedly bore the distinction of “being the only plastered house in Joplin. The house was later sold to Charles Workizer, G.B. Young, and then to the Bell Telephone Company. The phone company planned to demolish the house in order to build an office building.

Peter Schnur’s widow, when asked about the home, said, “When we first came to Joplin and built the old house in 1871 the present city of Joplin was nothing but a prairie, not a fence, and but few buildings in sight. There were not even any laws over the place; everybody did as they pleased. My daughter, now Mrs. Ed Poter, and my son, Burt Schnur, were at that time but three and two years old, respectively.”

Mrs. Schnur recalled, “I remember well the annoyance I underwent from the fact that there was no fence around our home behind which I could corral my children. One day Burt, then about three years old, wandered away from home and got lost in the tall prairie grass on what is now Wall Street. We found him, finally, within ten feet of an open shaft, and I that night issued an ultimatum to the effect that if there was not a fence around the house within a week, I was going to leave the district. I got the fence, and I have been glad of it ever since.”

The Globe estimated that the demolition of the house would take several days before the original two rooms of the home were reached.