Thanks to the sharp eye of Jim Perkins of the Joplin Fire Department, we discovered that our post from a few weeks ago of a photo of the 1907 Joplin Fire Department was in fact the 1902 Joplin Fire Department. Not only are we thankful to Jim for spotting this error, but he was kind enough to share with us a copy of the actual photo. Thanks, Jim!

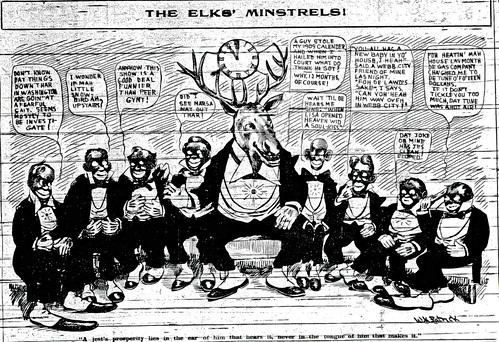

The Elks’ Present Their Imperial Minstrels

“Business men in blackface can be more amusing than professionals, especially when they strike a happy medium between the elite and the ridiculous.”

So began a review of the minstrel show put on by Joplin’s Elks Lodge, No. 501, in mid-January, 1909. Since the 19th Century, the minstrel show had been a steadfast form of entertainment based upon humiliating and stereotypical depictions of African Americans, often by white men with black makeup on their face. Generally, the performers adopted comical dialects exaggerated to effect laughter and ridicule. Entertainment in the shows ranged from comedy skits to song and dance.

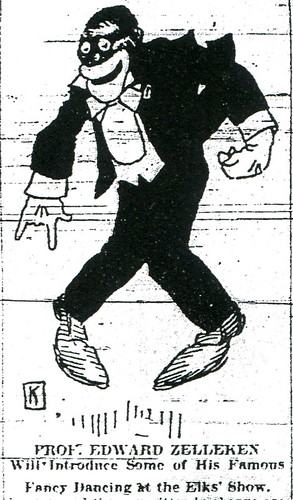

In an example of the acceptability of racism at the time in American and Joplin society, the minstrel show was produced by the Elks Lodge, a social organization of Joplin’s businessmen and reputable members of the city’s society. One advertisement for the minstrel show specifically noted the participation of Edward Zelleken, a member of one of Joplin’s most distinguished and wealthy families.

A small article that ran before the show promised an entertaining show and an opening which “should not be missed.” Tickets, the article claimed, were going fast, but good ones could still be reserved. An advertisement that ran near the article promised, “Ten Dollars’ Worth of Enjoyment For the Price of One.” The “Imperial Minstrels” as the Elks called their cast performed in the Club Theater. A follow up article the day after headlined, “Elks’ Minstrel Creates Furor Among Society” with the subtitle, “Business Men In Blackface Score Tremendous Hit.”

The jokes in the show ranged from the plain comedic to pokes and jabs at local businessmen, like the owner of Donehoo’s pharmacy, which was located at the busy intersection of 4th and Main. Other jokes were political in nature such as one about William Jennings Bryan recalled by a minstrel who claimed he had just stepped into an elevator in Chicago when he saw, “Mrs. William Jennings Bryan come running down the corridor waving her hand for the elevator operator to hold the car until she arrived. ‘You need not have hurried to catch the car,’ the elevator operator is said to have informed Mrs. Bryan, ‘I’d have waited for you.’ ‘Oh,’ replied the Commoner’s wife as she breathed heavily. ‘ I just wanted to show you that there was one member of the Bryan family who could keep in the running.’”

Another sign of the acceptability of the lampoon was the audience that turned out for the event. A reporter from the Joplin Globe described them, “Society turned out in all its finery to see something rich and rare…” Indeed, as the reporter noted, “And to a thousand, auditors giggled, laughed and te-heed until their faces ached while Joplin Lodge, No. 501. B.P.O. Elks, presented their Imperial Minstrels at the Club Theater last night.”

Source: Joplin Globe, 1909

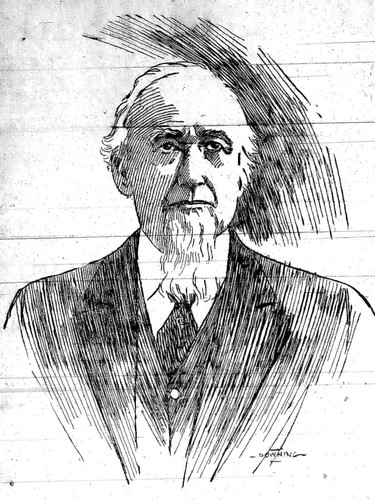

A.J. Blackwell Strikes Again!

In one of our previous posts, A.J. “Bear Fighting” Blackwell was mentioned. Blackwell, one of the earliest residents of Joplin, built the first opera house in Joplin. After serving a sentence for counterfeiting in the Missouri State Penitentiary, he left Missouri and founded the town of Blackwell, Oklahoma. He became a wealthy and well known figure who lived an interesting life.

According to an article from a Blackwell newspaper, Blackwell was accused of “periodical insanity and one of these spells is upon him.” For the last few days “he has been terrorizing the entire city and community with his threats, and being heavily armed continuously, it is a question as to what he might do.” Prior to his illness, he had Miss Effie Widick, a Blackwell school teacher, arrested for punishing one of his children. She was acquitted, but Blackwell was not satisfied. He traveled to Wichita, Kansas, in an attempt to have her indicted in U.S. federal court.

The news report claimed, “He once stood off a mob of negro haters with a Winchester and incurred the enmity of nearly the entire citizenship, which finally succeeded in ridding the town of the black race.”

Blackwell proclaimed that he was a member of every church in town and “has been dead twice and returned to life to warn the people to join as many churches as possible.” In the meantime, “he drives up and down the streets, hooting and yelling like an Indian, waving firearms and even defying the officers.”

Despite his insanity, Blackwell had somehow managed to invest in a coal company and direct coal to be shipped from Chelsea, Indian Territory to Blackwell.

When he died in 1903, his obituary failed to mention his bouts of “insanity.”

Source: Joplin News Herald

Mining and Picher, OK

The plight of Picher, Oklahoma is well known to locals of the Four State area. Discounting the disastrous tornado that ripped through Picher not too long ago, the lead and zinc mining resulted in a dangerous contamination of the town. The mining in Picher arose from the mining in the Joplin area, after all, the town gains its name from one of Joplin’s earliest mining entrepreneurs, O.S. Picher. Recently, Wired magazine has written an article on the town.

Addititionally, here’s a streaming video link to a entertaining documentary about Picher today and the effects of its mining past. It’s worth watching if only for some video of the process of mining, the same process used in the Joplin area.

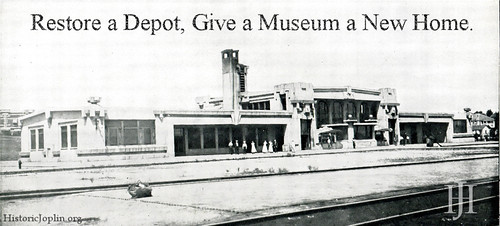

Globe Overview of the Union Depot

This last weekend, the Joplin Globe offered up a summary of the present situation with the Union Depot. In addition, the Globe put together a short timeline of events for the Depot from its opening over 99 years ago.

The summary covers in brief the past attempts at restoring the Union Depot, including an offer in 1973 by the Kansas City Southern to deed the Depot to the city. That proposal was nixed by the then head of the Joplin Museum Complex, Everett Richie. The excuse given then was the danger that the active train tracks posed to the museum and its collection should it be moved to the location.

The Globe managed to speak briefly with Nancy Allman, who was the lead in the effort to restore the Union Depot in the 1980’s. Allman did confirm that she still had in her possession some items from the Union Depot. This is good news for the restoration of the Union Depot. Even if Ms. Allman may not want to donate or sell the items, perhaps she would at least allow the restorers to photograph and measure the items for reproduction purposes.

The article also brings us via Allen Shirley the 3 Key Issues for the JMC about a move to the Union Depot. Let’s look at them one by one:

1) The Union Depot’s structural integrity.

Reports indicate that the work done in the prior restoration attempt went along way toward reinforcing and repairing structural integrity issues. In the walk through by the Joplin Globe with David Glenn, who was part of the restoration team from the 1980’s, Glenn comments on the strength of the building.

2) There’s less than 400 sq foot than the current museum.

As we’ve pointed out in previous coverage of the Union Depot question, there are two measurements being offered of the Union Depot’s space; one from the JMC and company, and one from Mark Rohr. It really boils down to the basement. One side counts it and the other side doesn’t. The basement also brings about another issue, as we’ll address below. There’s no reason more space cannot be constructed to supplement the Union Depot and done so in a simple, elegant and complimentary manner to the Union Depot. Here’s an off the cuff idea: enclose the concourse extending from the depot with glass, creating a beautiful glass hallway, and have the end of the concourse connect to a secondary building. There’s plenty of space available for such an addition. None the less, an addition may not even be necessary.

3) Environmental Control

Appropriately, the JMC Board is concerned about the presence of environmental control in the Union Depot. It seems that it would be a matter a fact element of any renovation of the Depot, particularly a restoration performed with a archival purpose in mind. In many ways, as photographs will often attest, the Depot is a blank canvas and now is the time where such improvements can be made and without the cost of tearing out existing material to replace it. (That former material has already been torn out!) Again the basement and the standing water. Here’s a simple answer: pump any water out, replace any water damage and effectively seal the basement walls. We’re not contractors here at Historic Joplin, but this solution does not seem to be one of great complication.

Mr. Shirley claims that the JMC board has not taken a position about the proposed move. We would disagree. No member of the board, or JMC Director Brad Belk, have not once said anything positive about the idea. In the summary, Mr. Shirley does note they support the preservation of the Depot, as we would hope of those who are charged with protecting the city’s history. However, supporting the saving of the Depot does by no means equate to supporting the idea of moving the museum. Fearfully, three members of the City Council appear ready to allow the Board to do as it wishes, which means doing absolutely nothing. The Board wanted Memorial Hall for a new home, turned down the offer by the Gryphon Building, and will have to be dragged into the Union Depot.

This is not the time for inaction. Joplin has embarked on a push of re-establishing itself as a city of beautiful buildings and one engaged not only with its past, but with an active present focused on its increasingly vibrant downtown. The relocation of the museum to the Union Depot would not only give more people a reason to visit downtown, but its better accessibility than the remote location by Schifferdecker Park would mean more would take the time to learn about the city’s glorious past.

The leadership of the city has proven itself innovative and bold by the successful and ongoing restoration downtown, we hope that the leadership does not back down at this important juncture. The City holds the purse strings of the JMC and if the Board of the JMC is not willing to play a part in the revitalization and the new beginning of Joplin in the 21st century, the City should tighten those strings. The Board of the JMC needs to accept that they will not always get what they want and assume a much more forward thinking position, lest they end up as dust covered exhibits they profess to preserve.

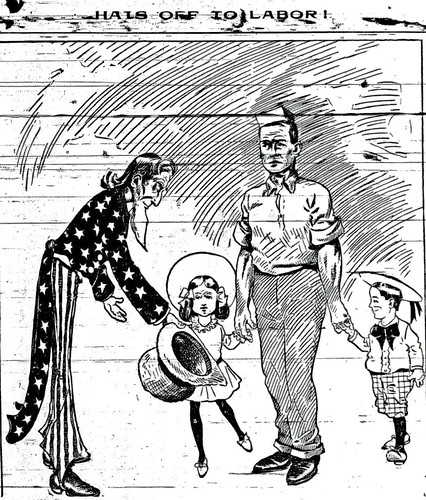

Labor Day

Among the holidays that Joplin celebrated with parades was Labor Day. For this Labor Day, we offer up an editorial cartoon from around 1908 that represents at least one newspaper’s feelings on the matter.

Source: Joplin News Herald

The Stars and Stripes

Englishman B.E. Dover and Irishman Harry Flynn began talking during a Salvation Army service held at the corner of Fourth and Main streets when Dover gestured to the American flag and remarked, “That’s a damned pretty flag but it’s a dirty rag and represents a dirty class of people.”

Flynn, who had met Dover for the first time during the service, was enraged. Flynn asked Dover to walk up the street with him, rather than disturb the Salvation Army service, and the two men began walking toward Fifth Street. Flynn asked, “What did you say back there?” Dover repeated what he had said, then fell to the street as Flynn punched him in the face.

“Take that, and that, you dog!” Flynn shouted, striking the Englishman as a crowd gathered to watch, cheering the miner on. After he decided Dover had taken enough punishment, Flynn walked off, but not before he declared, “You may be able to talk about the American flag as you please in England, but begorrah, when you come to the United States of America, you will have to be guarded in your speech.”

Dover picked himself up off the street in search of a police officer. By the time he found one, Flynn could not be found, and the newspaper remarked, “even if he had been on the spot, the crowd of spectators would never have allowed him to be taken to jail.”

Shredded Wheat

Joplin was a stopping point for many hoboes and railroad tramps and one can only assume that they hoped to find a square meal as they roamed its streets and alleys. On one occasion, hoboes were able to secure themselves a free meal, but probably not the feast they had hoped for.

Early one morning, young boys roamed the streets of Joplin with free samples of shredded wheat biscuits. At every doorstep the boys visited, they left a small box that contained two shredded wheat biscuits. It was not long, however, before a tramp caught on and began to trail behind the boys collecting the boxes of shredded wheat. Before noon “over two dozen tramps had been told the joyful tidings” and soon each tramp had at least “half a dozen boxes.”

Armed with plenty of shredded wheat, the tramps and hoboes fled to the safety of the Kansas City Bottoms, where “cans, old buckets, cups, and in fact anything that would hold liquid were pressed into use.” A nearby farmer was talked out of a “gallon or so of milk.”

The newspaper, which often frowned upon weary willies, declared that perhaps the boxes of shredded wheat “did more good to mankind” that day than if it had remained on the doorsteps of its intended recipients. One has to wonder if hoboes reminisced years later about the time they feasted on shredded wheat in Joplin.