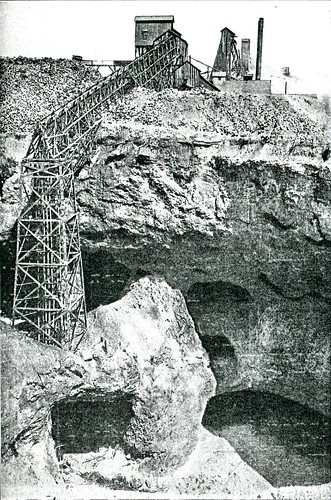

While the majority of Joplin’s lead and zinc mines were below ground, and in fact, much of Joplin is built above those shafts, there were some that were open to daylight. Below is a photograph of one of the best examples, the aptly named Daylight Mine.

History in the News: Historic Home in Joplin In Danger

This last weekend, the Joplin Globe published a story on the two story house on Schifferdecker Ave. The handsome house with a stone facade belongs to the late J.T. Goodman and his wife, Yvonne. The historic home, which likely dates to the early years of Joplin, was damaged by the May 2011 tornado. As seen in the above photograph, the home presently has no roof which is accelerating its danger of being declared condemned by the city. Joplin history expert and director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, Leslie Simpson, is presently trying to research the history of the home in an effort to help its preservation. So far, Simpson has discovered that it was on the property of Thomas Cunningham, one of Joplin’s wealthiest citizens at the turn of the century. Likewise, a mortgage deed indicates it might have even been built in 1873.

The historic home is currently before Joplin’s Building Board of Appeals. Unfortunately, due to the death of J.T. Goodman and a refusal by the Goodmans’ insurance company, the family has no funds to make the repairs needed to save the home. At the moment, Simpson is seeking to learn more of the home’s history which might translate to convincing the city Board of Appeals to spare the house more time to be repaired.

If you know anything about the house pictured above, located at 2725 S. Schifferdecker Avenue, please contact Leslie Simpson at the Post Memorial Library: (417) 782-7678. This is a piece of Joplin’s history, it needs to be saved!

Guest Piece: Joplin’s Black History – Leslie Simpson

The history of Joplin from the point of view of its black population has been difficult to trace. People are probably aware that Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, but his family left when he was still an infant. There was also the infamous lynching episode and subsequent flight of black citizens in 1903. But what about those who stayed, worked, raised their children, and died in Joplin? What were their lives like?

The earliest black inhabitants of southwest Missouri were, obviously, slaves belonging to the first white settlers. The 1850 slave schedule for Jasper County listed 212 slaves, including 3 belonging to John C. Cox, who later established the town of Joplin. There were 166 slaveholders registered in the county in 1861. Slaves were itemized on county probate records and deed transfers as well. It is heart-rending to read some of these documents. For instance, there is the account of an entire family (Sarah, Mary, Henry, Lewis, Susan, and Matilda) being sold for $1 and of three “copper-colored slaves” given to Arabella Sanders by her mother Margaret as a gift.

What happened to these people after they were freed? How did they earn a living? The 1870 census reveals the few occupations that were available to them–mill work, farm labor, and housekeeping. The mining boom, which put Joplin on the map in 1872, gave the freed slaves many more options. The 1880 census indicates that they held jobs in hotels, butcher shops, saloons, laundries, livery stables, in addition to doing farm and domestic work. They also worked in the mines. In fact, some were even mine owners! The Black Seven mine was owned by seven black men.

Joplin’s population grew from 9,943 in 1890 to 26,023 in 1900. Business was booming, and there was work for all. The 1900 census reveals an interesting trend. In addition to the previously noted occupations held by blacks, there were also more skilled professions listed–teacher, preacher, physician, barber, stone mason, plasterer, coachman, ice man, carpenter, taxi driver, grocer, upholsterer, and woolen mill, to name a few. But this trend did not last, probably due to the Great Depression and to the end of the mining era. In the 1937 Negro City and County Directory the majority of Joplin’s black citizenry were porters, domestic workers, and janitors. The only black-owned businesses were a dry cleaner, shoe shine parlor, barber shop, shoe repair shop, and a boarding house.

Speaking of 1937, the introduction to the Joplin city directory for that year, written by the Chamber of Commerce, enthuses that “The population is almost entirely white and almost entirely composed of intelligent, native stock, thereby eliminating the chief source of recurrent labor troubles.”

These are merely observations based upon a few historic documents. The black history of Joplin has yet to be written.

Leslie Simpson, an expert on Joplin history and architecture, is the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, located within the Joplin Public Library. She is the author of From Lincoln Logs to Lego Blocks: How Joplin Was Built, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture. and Joplin: A Postcard History.

Joplin Charity

Joplin has benefited from the charity of many over the past year since May, 2011. More than a century ago, Galveston, Texas, was virtually wiped out by a hurricane that claimed 6,000 to 12,000 lives. When that city was struck by a natural disaster, Joplin stepped forward in 1900 and offered over $25,000 to the beleaguered city, a sum close to $646,348.57 in 2010 dollars.

Joplin’s One-Armed Bandits

Gambling has been endemic to Joplin since the city’s foundation in the 1870s. However, it legally came to an end, at least in the form of slot machines, in 1952. Slot machines had been part of Joplin’s gambling past not that long before, when they formed part of the focus of a grand jury investigation into Joplin’s police chief and mayor in the 1930’s (based on officials “overlooking” their presence in Joplin businesses). After a state law came into effect, simply possessing the gambling devices became illegal. As a result, “approximately 3,000 pounds of “junk”” was collected by one local company. The Joplin Eagle Club, likewise, surrendered eleven machines to the Jasper County Sheriff’s Office, the total value of the machines estimated at $3,000. An article about the end of the slot-machines implied that at the time they were also familiar devices in Joplin’s other private fraternities and organizations, as well.

A Fireman from Joplin’s Past

Today’s post is a glimpse at one of Joplin’s earliest firemen. As previously covered on Historic Joplin, the Joplin Fire Department came into existence in the mid-1870s. Below is an unidentified fireman of the era who helped protect the young city of Joplin from the dangerous threat of fire.

The Number of Joplin’s Historic Buildings Decreased By One: Rains Building Lost to Fire.

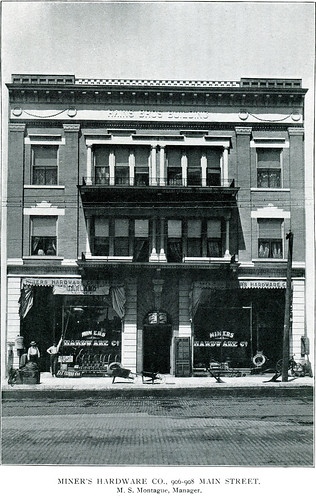

The next time you cruise down Joplin’s Main Street, you may notice that yet another of the city’s historic buildings has been lost. The Rains Building, located at 906-908 South Main Street, burned on Thursday night. The building, attributed to one of Joplin’s most prominent and prolific architects, August C. Michaelis, is a tragic loss.

Built in the Renaissance Revival style at the turn-of-the century for brothers Charles and George Rains, it brought an understated architectural elegance to the block.

Like many buildings along Joplin’s Main Street, it was home to several different businesses including the Miner’s Hardware Company, the Bullard-Bell Company, and the Roosevelt Hotel. By the 1970s, only the first floor was in use as an antiques shop. When the building was nominated for the National Register of Historic Places in 1991, it was noted that little, if any, alterations had marred Rains Brothers Building original design over the years, unlike many other buildings.

Image via Wikipedia.org, Rains Building circa summer 2010.

Image via Wikipedia.org, Rains Building circa summer 2010.

Here is a link to the Joplin Globe‘s coverage of the fire and here is a link to the National Register of Historic Places, a source for more detailed information on the building.