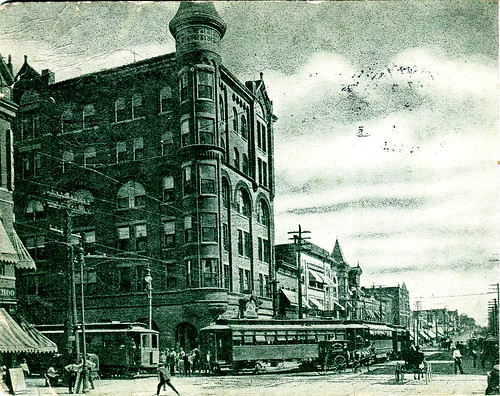

We engaged in another “What if….” this time looking up Main Street from the south.

This Building Matters: Louis Curtiss’ Joplin Legacy

In the past we have written posts about the construction of Joplin’s Union Depot. Now we would like to celebrate the life and work of its architect, Louis Curtiss. Sadly, his legacy is in peril. Of the over 200 buildings and projects that Curtiss designed, only 34 remained in existence by 1991. Of the 34 buildings, 21 were in Kansas City. Joplin is incredibly fortunate to have the Union Depot among its built landscape. If you care about history, if you care about cultural memory, and if you care about historic preservation you can appreciate Curtiss and Joplin’s Union Depot.

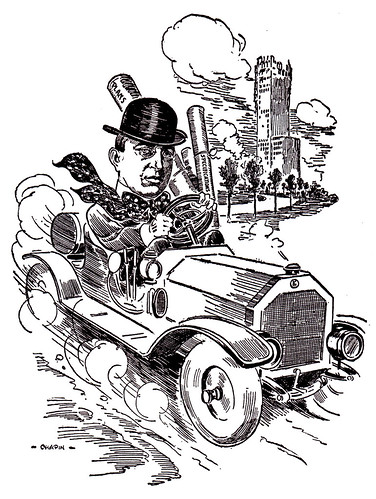

A native of Belleville, Ontario, Canada, Curtiss arrived in Kansas City, Missouri in 1887 at the age of twenty-two. Throughout his career, Curtiss was an enigma. He never discussed his life, never married, never had children, and ordered that his personal papers be burned upon his death. Curtiss was an incredibly colorful character. He loved fast automobiles: he would often roar around the city in a Winton runabout which, at the time, reportedly topped out at an amazing 30 mph. He loved women; he cut his own hair; and claimed to have studied architecture at University of Toronto and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, although historians have been unable to confirm this due to spotty recordkeeping.

Curtiss briefly worked as a draftsman in the architectural firm of Adriance Van Brunt. He then left to form a partnership with Frederick C. Gunn. Together Curtiss and Gunn designed a large number of courthouses across the Midwest and South. The current courthouse for Henry County, Missouri, is a Curtiss and Gunn creation. Regrettably, the original tower on the courthouse was removed in 1969. The Curtiss and Gunn designed courthouse in Gage County, Nebraska, still has its original tower. The partners also designed courthouses in Tarrant County, Texas; Cabell County, West Virginia; and Rock Island County, Illinois (its roof dome was removed). Even more interesting, they designed St. Patrick’s Parish Catholic Church in Emerald, Kansas.

After ten years, Curtiss and Gunn went their separate ways. Curtiss traveled abroad and studied architecture, but eventually returned to Kansas City. He designed a private residence dubbed “Mineral Hall” which survives today on the campus of the Kansas City Art Institute. Curtiss designed other private residences and commercial buildings at this time. Mineral Hall Link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mineral_Hall Note that the doorway is Art Nouveau in style.

Curtiss’ Folly Theater (now the Standard) still stands in Kansas City after construction finished in 1900. You can read about its colorful history here.

While living in Kansas City, the young architect had the good fortune of meeting Bernard Corrigan, a fellow Canadian who was a partner in Corrigan Brothers Realty Company, and for fifteen years the two worked together on a variety of projects.

Curtiss’ first large project, the Baltimore Hotel, was commissioned by the Corrigan Brothers. The hotel was located in downtown Kansas City at the corner of 11th and Baltimore. It was later demolished in 1939. Curtiss’ next major commission was the Willis Wood Theater. Located next to the Baltimore Hotel, the two were connected by a tunnel that was nicknamed “highball alley.” The theater was destroyed by fire in 1917. One of Curtiss’ residential masterpieces, the Bernard Corrigan House, still stands today. The house is a mesmerizing blend of Prairie, Arts and Craft, and Art Nouveau features. You can view pictures here and also here, too.

Curtiss established another fruitful partnership, although it was not with an individual, but with a company: The Santa Fe Railroad. Curtiss designed depots and office buildings for the railroad company all over the United States. He subsequently began designing buildings for the Fred Harvey restaurant system. During this time, he designed the Clay County State Bank, which is now the Excelsior Springs City Museum.

As years passed, he continued to design railroad depots, hotels, and private residences. In 1910, work began on Joplin’s Union Depot, a Curtiss creation. He also designed Union Station in Wichita, Kansas, which had survived the years since its completion in 1913. Interestingly, he designed the “Studio Building” to serve as his studio. Curtiss lived in an apartment in the building which coincidentally adjoined a burlesque theater. According to one individual who was interviewed years later about Curtiss, there was a balcony entry into the theater accessible only through Curtiss’ apartment, through which he could attend performances.

Beginning in 1914, Curtiss fell upon hard times. Many of his major clients began to pass away and the demands of World War One upon American society made new construction grind to a halt. Curtiss’ architectural style fell out of favor as new and reinvigorated styles became popular. He did achieve success with his work in the Westheight Manor subdivision of Kansas City, but he never regained his pre-war popularity. One of the residences he built in Westheight Manor is the stunning Jesse Hoel home: Historical Survey of the Westheight Manor Subdivision and Flickr Photo of the Hoel residence.

Another Westheight Manor home Curtiss designed was that of Norman Tromanhauser.

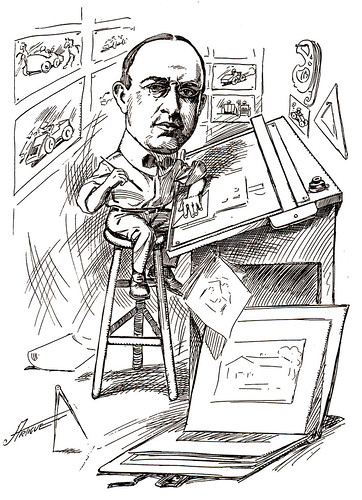

By 1921, Curtiss ceased to produce new architectural designs. Within a few years, on June 24, 1924, he died in his studio at his drawing board at the age of fifty-four. He was buried alone in Mount Washington Cemetery

The Joplin Union Depot matters.

Sources: Stalking Louis Curtiss by Wilda Sandy and Larry K. Hancks, Kansas City Public Library, Others.

The Missouri Mule

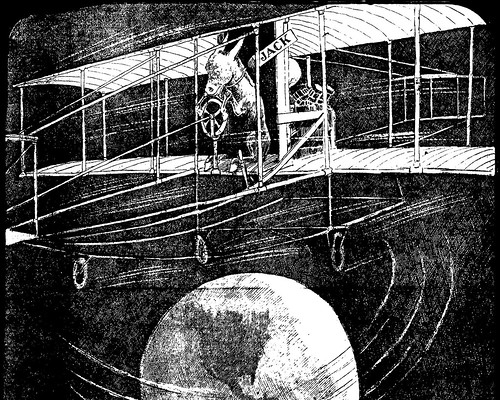

By 1911, the Missouri Mule was uniquely identified with mining as much as a miner, as seen in this illustration from a Joplin paper.

One of the most valuable sources of labor in the early days of the Tri-State Mining District was provided by mules. University of Missouri Professor Dr. Melvin Bradley partnered with the Missouri Mule Skinners Society to produce the Missouri Mule History Project. The project itself was a multi-volume collection of transcribed oral histories regarding the history of Missouri mules. Bradley sought individuals who had experience raising, selling, trading, and working with Missouri mules. One of the individuals he found was Lee Dagley, a native of Joplin, Missouri. The interview is illuminating for several reasons. First, it provides a look at how mules were used in the Tri-State Mining District, but it also allows one to understand life in early Joplin as seen through the eyes of one who lived it.

Lee Dagley was born in Joplin on July 23, 1888, in a small house on what is now today 1817 Michigan Avenue. He was one of thirteen children. Dagley’s parents came to Joplin in the early 1870s and soon found that the “best thing they had was a pick and a shovel and a wheel barrow.” His father bought an acre of land near Sixth and Pearl where the First Presbyterian Church stands. But Dagley’s mother protested and they moved near a large spring on what is today Campbell Boulevard. Growing up, Dagley recalled that Joplin was “all prairie…I herded cattle all over this country.”

According to Dagley, folks in Joplin did not eat much beef when he was growing up. He said, “There’d always be some man in the neighborhood that’d kill a beef and he’d take it around and we’d have beef for a little while. But pork was the main thing.” The family owned one milk cow which provided their milk. Dagley said he pretty much existed on “good milk and bread and butter.” To supplement their income, his family raised and sold chickens and turkeys. Turkeys brought fifteen cents. One turkey that they kept grew to weigh 65 pounds. It was so big and aggressive that Dagley would have to carry a stick to fend it off because of its propensity to attack anyone who came in through their front gate.

At first his father did not know how to mine, but quickly learned, and gained a reputation as “one of the best miners in the country.” But his father was not successful at mining. Still, Dagley recalled that in the early days of mining, miners could only dig 16-18 feet down into the ground before they hit limestone, and water would flood the shaft. Dagley’s father created a sluice trough that washed the lead ore that miners dug out of shallow mines. After washing the ore, someone would pick up the ore and deliver it to the smelter at Granby. Dagley’s father charged miners by the piece and usually made $1 a day. To make additional money, Dagley’s father rented out horses and worked as a “powder monkey.”

Dagley attended school, but quit when he was a sophomore because his father was ill. Dagley took a job at Junge’s Bakery for $3 a week and later $6 a week. He later worked a brickyard, but when the Thomas Mine Royalty Company came to town and offered $1.50 per day to drive a wagon, Dagley left the bakery and began driving a team.

Mining methods in the Tri-State region slowly advanced. Mules would pull cars full of lead ore on the surface, but they also worked below ground. Mules were lowered into the mines, sometimes in a sitting position. According to Dagley, the mines did not use big mules: “They were not big mules. They used small mules. The biggest one would probably weigh 900 lbs.” One particular mule barn that he remembered was “about 60 feet wide and 200 feet long.” The mine operators put “hundreds of tons of hay” in the barn. Dagley boasted, “Oh, this whole country out here was prairie hay, and the best prairie hay that ever was.”

At work, a muleskinner sat “on the front of the car and drive the mule. They’d pull ’em in and they had a track down there…up towards the mill.”

After the turn of the century, however, mines became less reliant on mules. Mines began using steam engines and motors. Mules were relegated to surface work, mainly pulling cars full of ore. The heyday of the mule in the mines of the Tri-State Mining District was over. Mechanization and advancements in mining methods had made them obsolete, but to the men who worked with them in the mines, there would always be fond memories.

* It is worth noting that although this fact was not mentioned in the oral history, Lee Dagley, according to contemporary press reports, was one of the few white men in 1903 who attempted to save Thomas Gilyard’s life from a lynch mob in Joplin.

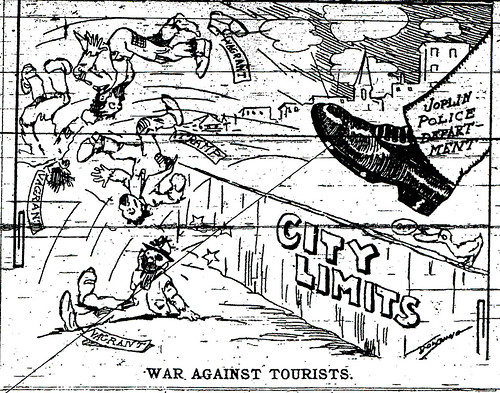

A Ten Cent Pork Chop

Joplin’s newspaper reporters loved to write about the tramps and hoboes that often drifted through town. The lifestyle of the “weary willie” was one that reporters seemingly found colorful and romantic despite the hardships that many of the men and women who traveled the road faced on a daily basis. Long before the 1930s, and in a time when relief agencies were few and far between, hoboes and tramps often found themselves one meal away from starvation. On one occasion during an economic downtown, a News-Herald reporter sought out a hobo and asked him what the smallest amount of money was that he could live on.

The hobo, after thinking for a moment, responded, “It is possible for me to live on 25 cents a day. I have lived on that amount but I did not spend any on it for a place to sleep. Of mornings, I would eat two chilies and for dinner, a ten cent pork chop. For supper, I would eat another chili.” To get the occasional piece of meat, the hobo would visit butcher shops and obtain meat that was otherwise reserved for feeding dogs. He would sleep in the woods rather than in town, lest he be picked up by the police for vagrancy. If a tramp or hobo were fortunate, he would sleep in boxcars, barns, or on railroad platforms rather than in the open.

When asked if he ever became desperately hungry, the hobo told the reporter, “I have been so hungry that I was too weak to walk, but did not become desperate. I felt that I was near the place where I would not have to spend from twelve to eighteen hours per day being turned down by people, with the world against me and no pleasure whatever.” Instead, he confided, “I also knew that after I reached a certain stage, people would feed me, for fear I would die on their hands.”

Joplin had more than its fair share of the “knights of the road.” There were individuals that loved the lifestyle, but there were others who found themselves riding the rails because of sudden, severe economic downturns that cost them their livelihoods. Funny how some things never change.

Worth Block … What if?

Brown, July 21st 2011 |The Good Ol’ Days?

Despite the trappings of a modern city, there were still some old fashion headaches in the way of Joplin's progress.

Back in 1897, much of Joplin was an open sewer. The sewer system at the time was “plagued” and the “city dads” decided to direct various sewer mains into Joplin Creek. This was when the city was “young and was comparatively unsettled north of A street.” But the city fathers did not foresee that Joplin Creek would be dammed in several spots. This caused the sewage to back up and grow even more fetid. After being exposed to the sun, the raw waste was enough “to sicken a maggot or act as an emetic on a jackal.”

According to the Globe, the stench alone had caused “an immense amount of sickness between B and D streets, and there is good reason to believe that one death resulted from it.” It was reported that at the corner of C and Main streets two families living in adjoining houses “had six people sick at the time, three in each home” with other families in the area similarly affected.

The paper declared, “It is the plain duty of the authorities to jerk those dams out of the creek and to keep them out. It is also their plain duty to see that the sand is removed that chokes the channel up to and to see that is kept clear.” If the creek were not kept clear of dams, then there “will be much loss of life…The city cannot afford to have its citizens killed off in this sort of a manner. Death comes all too soon without keeping a trap like this to stink people to death.”

The day after the Globe groused about the condition of Joplin Creek, Mayor Cunningham ordered Marshal Morgan to inspect the creek, and, if the conditions were as stated, to have the dams removed. When Morgan contacted the individuals responsible for the various dams, they complained that they owned the land that the dams were on, and that “they would like to see the color of the man’s hair who could make them take the obstructions out.”

Morgan would have none of it. He told the dam owners to remove their dams within twenty-four hours or else they would face arrest. The Globe proclaimed, “There must be no let up on the part of the authorities until the channel is as clear as a whistle, and it should be kept that way forever.”

Mayor Cunningham got his way and conditions improved. Sometimes the good old days weren’t so golden after all.

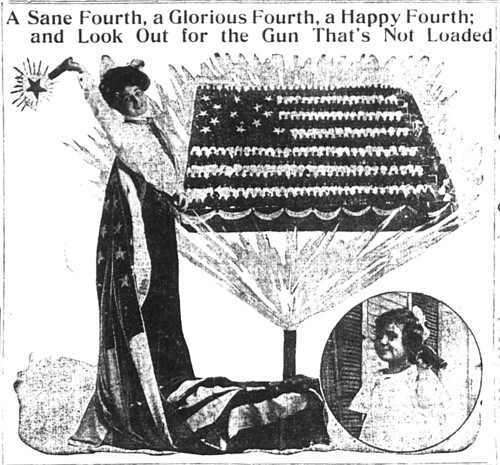

Have a Safe and Sane Fourth of July!

A century ago, Joplin adopted the idea of promoting a Fourth of July that was both safe and sane. The illustration above offers a glimpse at this campaign and below, a familiar company advertising in Joplin on the Fourth. The idea of promoting a safe Fourth was supported by an article noting the harm already received by the dangerous fireworks. One case involved a boy, whose friends involved in a fight, found his hand badly burned when the firework he was getting ready to throw went off prematurely (the boys quickly made peace after this casualty). Another boy, it was reported, suffered terribly burns on the neck and hands while shooting off “fire crackers” and two men, Roy Loving was shot in the hand by a blank gun cartridge and another, Earl Van Hoose severely burned by a “cannon cracker” which went off as he was throwing it.

Needless to say, have a fun, safe, and “sane” Fourth of July!