Thankfully, Halloween has for the most part shifted away from the “trick” to the “treat” over the last century. In the cartoon below, we catch a glimpse of some of the mischief that Joplin’s young men got up to one Halloween many years ago.

Our Man in Havana

Joplin’s dapper James H. “Jimmy” Worth, owner of Joplin’s famed Worth Block, traveled to Havana, Cuba, and wrote the following letter to his friend E.R. McCullum that was published in a Joplin newspaper:

“Friend Mack: I am well at the time and hope this will find you the same, although I am tired of seeing the prettiest country in the world. I have been most favorably impressed with the cleanliness of the city and the salubrity of its climate. Having visited nearly all the cities in the United States and Canada, I believe I am conversant with municipal conditions in all of them, but I have never see any place that would compare with Havana. I have been in every direction and found the sanitary conditions excellent. It has surprised because of its novelty.

The courteous conduct of the people is another eye-opener. I do not speak Spanish very well and expected to be embarrassed most of the time while I was here, but the innate helpfulness of the native population put me at my ease whenever a difficulty arose. I was dining at a Spanish restaurant the other night and would have had difficulty in ordering my meal had not a Cuban sitting at another table noticed my predicament and voluntarily came to my assistance.

The modern equipment of the financial institutions here are a revelation to all visitors from the states. They have a bright future. I went out and saw the old Spanish forts and visited the negro schools and attended the courts, and was greatly amazed at the thoroughness with which everything is being done here. I haven’t time to write more now, but will follow this with another. My regards to the boys.

JH Worth.”

Men and Dust

In a previous post, we covered Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins’ visit to Joplin in 1940. The reason for Perkins’ visit was to participate in the Tri-State Silicosis Conference, a gathering of industry and labor leaders to investigate and highlight the danger of silicosis. At the conclusion of the conference, a brief documentary film simply titled Men and Dust was shown in the Connor Hotel. The film was produced by the noted Great Depression era photographer Sheldon Dick. Only sixteen minutes long, the film focused on the the danger posed by silicosis generated by the dust created by lead and zinc mining. Dick’s film is surprisingly experimental with a unsettling score and a dramatic narration that has a jarring effect on the viewer. It is an important piece of Joplin’s history because of its haunting advocacy for the welfare of the region’s miners and their families and its stark images of the men who worked the Tri-State Mining District during the Depression era.

We encourage everyone to view it who has a chance.

More on the Early Joplin Black Community

In 1915, Theodore Baughman, a correspondent with the African-American newspaper Topeka Plaindealer, wrote a brief, but detailed account of Joplin’s black community. Baughman observed that although there were less than a thousand African-Americans in Joplin, there were four black churches, and a number of fraternal organizations, though, he noted, none of them had their own meeting hall.

Baughman disappointedly observed that the black community in Joplin was not “given very much to commercialism.” Still, in the paragraphs that followed, he wrote about a few entrepreneurial souls who sought to make a

P. Fred Romare, the “harness king” of Joplin, was born December 8, 1858 (according to a 1920 passport application) or in 1860 (according to his Missouri death certificate), in Chester, South Carolina.* His father, Paul Romare, was a native of Sweden who worked as a bank clerk in Chester. It was there that he fathered Fred with an African-American woman named Esther. When the Civil War broke out, Paul Romare enlisted in the Confederate Army, and served the duration of the war. After the war ended, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, married a white woman, and eventually became the president of the Atlanta National Bank. He left his mulatto son, P. Fred Romare, behind in South Carolina.

Between 1880 and 1910, P. Fred Romare and his wife Rosa moved to Joplin, Missouri, from South Carolina for reasons still unknown. As a youth, he worked as a carriage maker, and he continued this trade in Joplin. Romare became well known for his wide selection of carriages, buggies, and harnesses. He housed his business in a handsome two story brick building located at 818 Main Street and employed three white men as harness makers. Romare lived at 1826 Pearl until his death on October 20, 1934.

Baughman also called on the Reverend J.N. Brownlee at his real estate office at 521 ½ Virginia Avenue. Brownlee was fortunate to still be alive after he became embroiled in a scandal in 1912 that raised the ire of Joplin’s white community, and led to threats of lynching. According to one newspaper account, young white girls allegedly would meet at Brownlee’s office to drink brandy, beer, and wine. One young white woman, Pearl Nugent, a seventeen-year-old stenographer employed by Brownlee, was found dead in Brownlee’s office. The coroner’s jury ruled she committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid.

Fortunately for Brownlee, attorney John Castillo produced letters that showed Nugent had allegedly been assaulted by a married white man named Walter Bishop from Chitwood, and that she may have committed suicide as a result. The coroner’s jury, in the course of its investigation of Nugent’s death, raised questions about Brownlee’s habit of employing young white women in his office, his lewd treatment of his employees, and his alleged attempt to blackmail the man accused of assaulting Pearl Nugent. Scared of a repeat of the events of 1903, when Thomas Gilyard was lynched in downtown Joplin, many black residents began leaving the city, though one paper noted it was mainly the “shiftless class” that left. The paper added, “No mob plays will be tolerated by the police, however, and the blacks will be protected if there is any hint of uprising.” Joplin Police Chief Joseph Myers warned it was against the law to incite mob violence and that he would not hesitate to stop talk of lynching Brownlee with force.

In an indication of the limited opportunity for black men in Joplin at the time, many of Baughman’s “success” stories were men who worked as janitors at Joplin’s leading businesses. Benjamin Davis worked at Aldridge’s, Arthur Young and Frank Caldwell both worked as janitors at Miner’s Bank, and Joseph Stover was the head janitor at the Keystone Hotel. Although today many may not think that working as a postal carrier a prestigious job, Baughman considered it one for African-American men during this time and N.T. Green, one such gentleman, Baughman wrote, “is one of Uncle Sam’s trusty men.” There were also enough African-Americans in Joplin to keep Dr. J.T. Williams busy after he graduated in 1908 from Meharry Medical College, a historically black medical school in Tennessee.

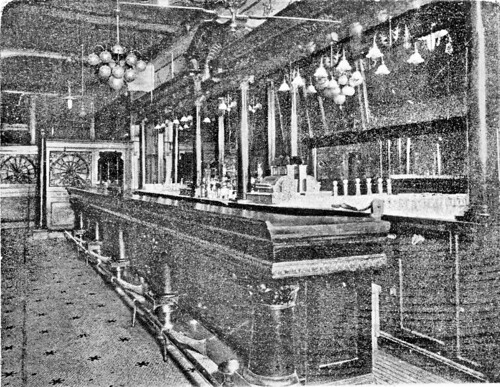

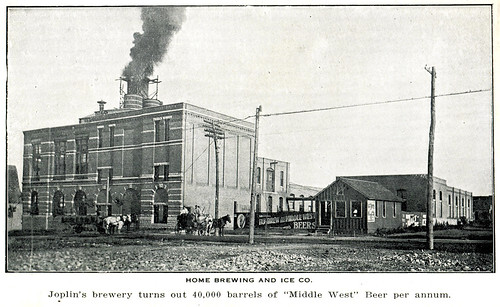

The Turf Bar, which one will find mentioned in the pages of the Joplin newspapers, was possibly owned by George Lindsay. The Turf was located at 123 Main Street and served Budweiser, Middle West, and Falstaff beer. In 1914, under a different owner, it was considered one of the finest bars in Joplin. J.W. Brown’s People’s Café was located just down the way at 109 Main Street

While turn of the century Joplin was a bustling growing city, it was also a city that limited the many opportunities available to the color of one’s skin. Joplin’s early African-American residents none the less persevered to the best of their abilities to build a life for themselves and their families in Southwest Missouri.

Afternote:

The African-American artist, Romare Bearden, was named after P. Fred Romare, who was a friend of his great-grandparents. He stated in an oral history that the name was pronounced, “ROAM-a-ree.”

The Architectural Legacy of Garstang & Rea: The Joplin Casket Company Factory

The next photograph in the Alfred W. Rea portfolio series is the Joplin Casket Company Factory. Regrettably, we have not been able to find much on the Joplin Casket Company, but we can at least tell you that it built in 1907 at a cost of approximately $278,000 present day dollars. J.A. Wilson was president, B.W. Lyon, vice-president, J.H. Spencer, secretary, and it was located at 4th NW Cor RR (unfortunately, we’re unable to figure out where this address was exactly).

Update!

Thanks to the sharp eyes of Historic Joplin followers, Mike Sisk and Clark, we were delighted to learn that the former factory building still stands between Division and School streets on Fourth Street and is owned by the Empire District Electric Company.

Where Everybody Knows Your Name

Driving along the streets of Joplin, one will occasionally recognize an old corner store standing forlornly in the midst of modest homes, a survivor of a simpler era. Though ragged and ramshackle, these sentinels of commerce were once lively, thriving cornerstones of many a neighborhood. As the era of chain grocery stores dawned, these mom and pop operations slowly faded from existence, leaving only memories.

One such store was owned by Curtis and Nancy Douthitt. The couple owned a small grocery store at 202 North Gray Avenue in Joplin that originally opened in 1903. Like most store owners, they lived above their store. When they bought the store in the 1940s, there were 139 neighborhood grocery stores in Joplin, including three others on the same block. The Douthitts sold staples like milk, bread, sugar, salt, and candy. In the early years, you could purchase two cookies for only a penny. At one time, the store employed five employees and a delivery boy. For a twenty-year period the couple worked seven days a week to meet their customers’ needs. The store’s willingness to extend credit to its patrons and quality service kept the Douthitts in business. Nancy Douthitt said that, “We could write a book about the three generations who’ve gone through the store. Grown men come back to Curtis now and say, ‘Do you remember me?’ and he does.”

But in the spring of 1987, Curtis and Nancy announced that they were closing up shop, and that their building would be for sale. Only one neighborhood grocery, Melin’s, reportedly remained open in Joplin after Douthitt’s grocery closed. Melin’s, it is worth noting, was run by Margery and Charles Melin. The Douthitts noted that they would be shopping in a new grocery store and, as Curtis remarked, “We’ve been in them before just to look, but they never had anything we didn’t – just more of it.”

The Douthitt store still stands at 202 North Gray Avenue, a reminder of a slower, more friendly time.

There’s No Such Thing as a Free Lunch

Joplin’s early Chinese community, although small, was tenacious despite being frequent targets of crime and racism. On a Saturday night in late January, 1916, a free-for-all erupted at the Low Shanghai restaurant after a patron refused to pay for his dinner. When confronted by Jung Toy, the owner of the restaurant, the man put on a pair of brass knuckles and hit Toy. Members of the Chinese wait staff rushed to the assistance of Toy which then induced a number of other diners to join the fray. Brass knuckles, a knife, and several chairs were used in the ensuing melee. Sixty year old Jung Ginn, who was also known as John Lee, was seriously injured when someone hit him over the right eye with a pair of brass knuckles. The attackers fled the restaurant, but G.H. Ritter, Thomas Hildreth, and Harvey B. Young were arrested a short time later.

Jung Toy had immigrated from Canton, China, possibly in 1882, and likely named his restaurant after the region’s greatest city. The attack did not dissuade Jung Toy from remaining in the restaurant business. A glance at the 1920 census reveals that Jung Toy remained in the business at least four more years. However, by 1930, Jung Toy’s life had taken a turn for the worse. If the same Jung Toy, he reappears in the census in Rexford, Montana, a widower (he had been married in Joplin) and reduced to a simple cook at a railroad restaurant.

The Architectural Legacy of Garstang & Rea: The Christman’s Building North Annex

The next photograph in our Alfred W. Rea portfolio series is the north annex to the Christman’s Department Store built approximately in 1903 as storage for the store located at 5th and Main Street. Christman’s, which deserves and eventually will get a much more thorough post, traced its origins to Pete Christman who came to Joplin in 1890 and with his brother, opened up a joint venture at 5th and Main Street in 1892. Business obviously boomed for the Christmans and when they needed extra space for their burgeoning store, they contacted Garstang & Rea to build them that space. Later, a second annex was built adjoining this one on its south side. Also in the photograph is the Joplin Tobacco Company, and a glance at the large sign above which reads, “Matinee Today” is likely for the neighboring Paramount Theater.

Happily, the annex still stands today and can be visited by going to the intersection of 5th Street and Virginia Street.

The Missing History of Fourth and Main Street

More than a century ago, a visitor to the bustling growing city of Joplin could have stood on any of the four corners of the intersection of Fourth and Main and viewed the history of the former mining camp writ large in the buildings about him or her. The ability to taken in the “epochs” of Joplin’s history with a glance was not missed by Joplinites of the era, and one reporter of a city papers wrote,

“The noonday shadow of the old frame landmark of the early seventies almost brushes the base of the half million dollar edifice that represents the highest achievements in building construction of the twentieth century. The monument to the days of Joplin’s earliest settlement seems to crouch lower and more insignificant than ever, now that a colossal hotel has been erected within less than a stone’s throw of it.”

The “old frame landmark” was the Club Saloon owned by John Ferguson until his death on the Lusitania (learn more about that here) and the “half million dollar edifice” was none other than the Connor Hotel, completed in 1908 and considered by many the finest hotel of the Southwest. Unmentioned above were the Worth Block and the Keystone Hotel. A visit to the intersection today, however, would find none of these buildings remaining.

A step back in time, when these four buildings still stood, would let the visitor see Joplin’s history as built by man. For reference by today’s geography, imagine that you are standing on the northwest corner of Fourth and Main Street with the Joplin Public Library at your back. Behind you in the past would be the towering eight story Connor, across the street to your right was the two story, wood-framed Club Saloon, where the current Liberty Building stands, to your left was the three story Worth Block, now home to Spiva Park, and directly diagonal from you would be the six story red-bricked Keystone Hotel, gone for the one story brick building today. The same reporter from above offered descriptions of how each of these four buildings revealed the chapters of Joplin’s past. The history that the Club Saloon represented was one of a camp fighting to become a city.

“When the frame structure at the southwest corner was the leading structure of the city, the site of the present Connor Hotel was a frog pond and the deep booming of the inhabitants of the swampy places echoed over the sweeping stretch of open prairie land.”

At the same time, the land where the Keystone Hotel eventually grew, was a mining operation owned by Louis Peters. The reporter is quick to allay fears of sink holes and noted that the drifts and shaft of the mining were filled before the property was sold. The Club Saloon’s home was bought from its owners in Baxter Springs, Kansas, by Oliver Moffett (E.R. Moffett’s son), Galen Spencer, and L.P. Cunningham, among others, and brought to the young mining camp to become the town’s early center. It was first used as a grocery store and flanked on either side of it were “shacks of disreputable apperance.” In the frame building, reportedly, one of Joplin’s early grocers and councilmen, E.J. Guthrie was killed. It was not the only frame building to be brought to Joplin, but those failed to survive for long. The Club Saloon was immuned perhaps because of the temperament of its owner, the ill-fated John Ferguson. Often, he turned down offers to buy it and once Ferguson allegedly declared, “If you would cover the entire lot with twenty dollar gold pieces, it would not be enough. I think I shall keep it.”

Across the street, so to speak, the old frog pond was shortly developed into a three story brick building, the original Joplin Hotel. Described as a “palace” amongst the other contemporary buildings of Joplin, it was given credit for shifting the center of the new city from East Joplin to the area formerly known as Murphysburg. The presence of the brick building spurred the construction of others, particularly on the east side of Main Street. Among those building was Louis Peters, who continued his mining, but also built a two-story building at a cost of approximately $4,600 on the northeast corner. The new building replaced one that had burned to the ground and was built in less than two months, completed in the December of 1877. Later, a third story was added to what was then called the Peters Building, but became better known as the Worth Block when James “Jimmy” Worth became the owner (precipitated by Worth marrying a co-owner of the property).

As slowly a recognizable Fourth and Main Street began to emerge, Joplin was still a young city that had more in common with a mining camp than a growing metropolis. Saloons proliferated, gambling was common, and other vices not spoken of in good company. This period of Joplin’s past was described as so:

A crimson light hung high over Joplin, shedding its rays over a great portion of the town, would have been an appropriate emblem of the nature of the community. Pastimes were entered into with a wantoness that brought to the town a class of citizenship not welcome in the higher circles of society. But if, in those days there was a higher circle, its membership was limited. Society existed but it was in true mining town style. There was in evidence the dance hall, the wine room and the poker table. The merry laugh of carefree women mingled with the clatter of the ivory chips on the tables “upstairs” and the incessant music of the festival places sounded late into the night, every night of the week, and every week of the year. No city ordinance prevented citizens from expectorating tobacco saliva upon the sidewalks; in fact, the sidewalks were almost as limited as was the membership of the exclusive upper circles.

In 1875, a flood swept through Joplin, and washed away homes, flooded mines, and even killed some Joplinites. The damage, in 1875 dollars, was almost $200,000. For all that was lost, the city continued to gain in wealth, growth and citizens. Ordinances and laws were put in place and a more determined citizenship to see their enforcement. The lawlessness that had persisted in the open air withdrew, the “secrets of the underworld of the Joplin…” were not “broadcast as they were…” The surge of mineral wealth saw more bricked buildings rise and the new owner of the southeast corner of Fourth and Main, E.Z. Wallower, saw more to gain in building than in mining. In 1892, construction of the turreted Keystone Hotel began. Not long after, the intersection was just short of the Connor Hotel in its appearance. This was remedied, as noted above, in 1908, just sixteen years later. In that span of time, “many fine edifices were erected.”

Until the demolition of the Club Saloon, at a glance, one could have seen the history of the city. From the very first days when a wood frame building was a sign of progress, up from shanties and tents; and then the brick constructions of the Peters Building that became the Worth Block, as the first inclinations of wealth from mining began to show progress; and finally, the raising of the Keystone and the Connor, when millionaires brushed elbows as they walked the sidewalks from the House of Lords, and Joplin was in the thick of its first renaissance. A visit to the intersection today leaves nothing of this history to be learned at a glance. The Liberty Building, which now stands where the Club Saloon once stood, is a bridge back however, witness to all of the former inhabitants of Fourth and Main Street but the Club that it eventually replaced. As are all the historic buildings of downtown Joplin, so while some of old Joplin is gone, much thankfully, can still be enjoyed and that history known with a glance.