Many months back, we created video slideshows from old photography books of Joplin and posted them on Youtube. Now they are accessible on our site without hunting them down elsewhere. Just click on the “Video” tab at the top of the site on the right. Enjoy!

Joplin’s Snob Hill

Tucked away in the northwest corner of Joplin is the neighborhood known as “Roanoke.” Over the years the area has also been known as “Snob Hill” and “Mortgage Hill.”

The land originally belonged to Andrew McKee, an early resident of Jasper County, Missouri. McKee, who filed for the land in 1851, did not live to enjoy the property. He died in 1852. The land then passed into the possession of William Tingle in 1860, but due to the coming of the Civil War, Tingle had little opportunity to make use of the property. Notably, Tingle hauled pig from Jasper County to Boonville, Missouri, which was a considerable distance at a time when the only method of transportation available was a wagon, as the railroad would not arrive in the region until well after the close of the Civil War.

In 1866, Tingle sold the land to Henry Shepherd and other individuals. Later, the Granby Mining and Smelting Company leased the land and eventually purchased it. The company eventually sold forty acres to Peter A. Christman who then deeded the land to the Joplin Roanoke Realty Company. The company was established in 1907 with Christman and his three brothers as the principal stockholders.

When word spread that the area would be developed into a new residential neighborhood, the news was met with skepticism. Many believed that the area was too rough and steep. Land in the new neighborhood sold for $600 an acre which, for the time, was expensive. The purchase price did not include the cost of sidewalks, grading, paved streets, nor did it include the expense of laying new water, sewer, and electric lines.

The Christman brothers and the Joplin Roanoke Realty Company were joined by Edmund A. Bliedung, Phil Michel, J.F. Osborne, and Bob Fink. Peter Christman and Bliedung were business partners, having founded Joplin’s Christman Dry Goods Company in 1895. It was Osborne who christened the neighborhood “Roanoke” and Peter Christman who created the street names such as Glenview Place, Hampton Place, Richmond Place, Islington Place, and Jaccard Place. The tony English inspired names were joined by a few older Joplin names such as North Byers, North Moffet, North Sergeant, and North Jackson Avenues.

Mrs. Ocie D. Hunter and Leonard Lewis were the first to build “cottages.” The distinction of the first large two-story house went to the Dana residence located at 802 North Sergeant. Grocer Nicholas Marr built a large home at 615 Hampton Place. Ethelbert Barrett built the home at 1002 North Moffett Avenue. When he died in 1936, Barrett was buried in an ornate tomb in Mount Hope Cemetery. Other early residents included C. Vernon Jones (816 North Byers); Dr. Mallory (827 North Sergeant); J.F. Dexter (920 North Sergeant); Fon L. Johnson (702 Glenview); William J. Creekmore (915 North Sergeant). Creekmore was known as the “king of the Oklahoma bootleggers.”

Despite the fact the neighborhood was home to several wealthy residents, it did not escape the sorrows that less wealthy areas of Joplin experienced. In 1950 William Creekmore’s daughter Gwendolyn was found murdered at the family home in Roanoke. The coroner’s jury ruled she came to her death at “by a party or parties unknown to jury.” Her murder was never solved.

Note: We tip our hat to the late Dolph Shaner who published a brief history of Roanoke that was used to create much of this post.

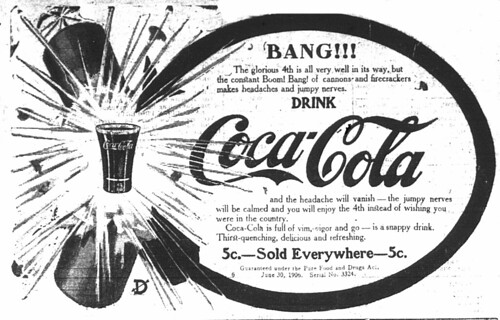

Have a Great Fourth of July!

The Fourth of July was as popular a holiday in Joplin in the past as it is today. The same emphasis on safety with fireworks continues today, though, perhaps not so much the worry on loaded firearms. A local paper illustrated the dangers of firecrackers, be it from boys throwing them at passersby in the street for laughs to other boys using the explosives as potential tools in arguments. One such event occurred as written:

“Three negro boys were walking down Fourth street this morning with their pockets bulging with fire crackers. As they passed the Miners Bank building two young men, prominent in business circles, began to “kid” the boys about the Jeffries-Johnson fight. The negroes became “riled” and in a moment were willing to take their contemporaries on. In the meantime, one of the negroes, who gave his name as Fred Jackson, stepped behind a telephone post and lit a big fire cracker. It exploded in his hand and the boy’s cries drowned the arguments. In an instant the miniature race war ceased. The young men grabbed the negro and carried him to a drug store, where he was given medical aid. the negroes apologized for their quarrel and the white boys “Set ’em” up for the sodas.”

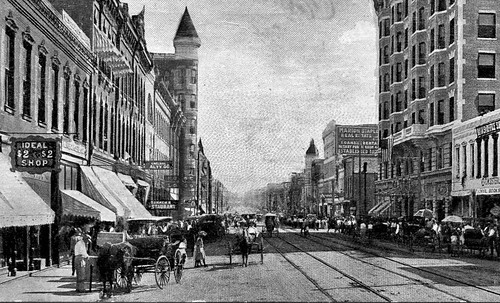

A Car Accident

“Great Excitement prevailed for a time, but this soon subsided…” In 1906, automobiles were still a new and intriguing sight on the streets of Joplin. The motorized fire engines were still a dream and the road mainly belonged to horse drawn buggies, wagons and trolleys. Thus, it was still quite a newsworthy event when one of the new machines accidentally plowed through the front of A.C. Webb’s automobile establishment at 2nd and Joplin street. A Joplin paper described the event:

“The automobile has always been noted for its liability to do things, but this characteristic was fully demonstrated yesterday afternoon when a runabout of this make crashed…tearing down a large portion of the building, breaking the glass in both windows and doors and not injuring the machine in the least.”

The unfortunate driver was Gus Mattes who had attempted to drive the vehicle into Webb’s shop but instead failed to slow down and completely missed the entrance, but did not miss the brick wall (“with great force.”) Surprisingly, despite the fact that Webb’s shop had suffered damage described alternatively as “demolished” and “splintered” the actual automobile received only a “crack in the glass of one of the lamps.” Before the day was done, the shop was already under repair, and undoubtedly, Mr. Mattes’ vehicle as well.

Incidentally, A.C. Webb’s shop was only a few blocks away from the Joplin Fire Department. When Joplin firemen responded to a fire a couple years later behind a steering wheel, its creator was Webb.

The Devil of East Joplin

Back one hot August summer in the 1920s, the Devil roamed the streets of East Joplin. A number of women and children reported a tall figure that resembled Beelzebub jumping out of the darkness at them and then running away. Mrs. W.H. Longacre watched in horror as a satanic figure ran in front of her car as she drove her children home. Mrs. Longacre’s report to the police went unheeded.

Doors were locked, windows were barred, and a small group of East Joplin men prowled the streets with their shotguns loaded. Rumors swirled as to whether or not it really was Old Scratch or just some harmless prankster. Some believed it was a prankster who wore armor underneath his costume to keep him safe from harm. After it became known that men were searching for the Devil armed with shotguns, Vard I. Cowan, a laborer for the Southwest Missouri Railroad Company, confessed to playing tricks on unsuspecting victims. He had used it at a church party earlier in the year and had such a good time that he continued to play tricks on residents the rest of the summer.

Some expressed their belief that Cowan’s antics were connected to the nearby Nazarene Church, but the pastor, Rev. F.C. Savage, denied that he or the church was involved with Cowan’s mischief. Mrs. Cowan, meanwhile, declared, “He has quit it. We don’t want to get into trouble.”

There were no further reports of the Prince of Darkness lurking on the streets of East Joplin.

Guest Piece: Leslie Simpson – Joplin’s Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian House

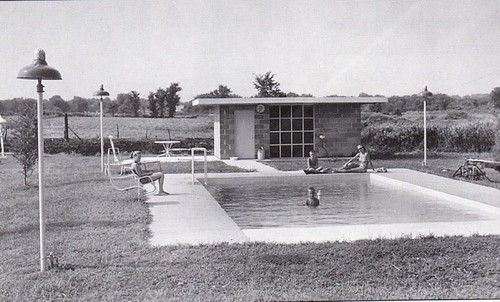

In the mid-20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright invented the concept of “Usonian” houses, which were based on the utopian ideals of simplicity, economy, and convenience. The first step in constructing a Usonian house was to lay down a concrete platform with cast-in heating pipes. Next came a grouping of brick supporting screens, creating a chain of linked boxes. The brick supports were topped by a series of flat concrete roofs, with a higher roof over the living-dining area and lower ones over the bedrooms and bath. The difference in roof heights allowed extra light to come in through clerestory window strips. Light also streamed in through floor to ceiling windows, usually overlooking a garden or pool.

One of these Usonian designs was built on the outskirts of Joplin, ¼ mile west of Stone’s Corner on Highway 171. Joplin architect Robert Braeckel adapted Wright’s plans to construct this ultra-modern dwelling for Stewart and Naomi Ruth Stanley in 1950. All steel construction supported Carthage limestone walls and large expanses of glass. Copper tubing built into the floor provided radiant heat. The ultimate in modern living, the house also featured a pool and bathhouse.

Unfortunately, I had to use past tense in my description; the house was demolished May 3, 2012. It is ironic as well since May is National Historic Preservation Month. This month’s Preservation Magazine devotes the entire issue to Frank Lloyd Wright architecture and the efforts to preserve it.

This piece was adapted from Leslie Simpson’s “Little House on the Prairie” that was published in Joplin Souvenir Album, G. Bradley Publishing, 2001. Photographs courtesy of Leslie Simpson and the Post Memorial Art Reference Library.

Leslie Simpson, an expert on Joplin history and architecture, is the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, located within the Joplin Public Library. She is the author of From Lincoln Logs to Lego Blocks: How Joplin Was Built, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture. and Joplin: A Postcard History.

Currently at the Post Memorial Art Reference Library

From 1pm to 5 today, you can visit the Post Memorial Art Reference Library to see artifacts of Joplin’s past. Ranging from a key to the Connor Hotel to an embroidered towel from the Keystone Hotel, plus a number of other items, you have the chance to get a glimpse of Joplin’s past through “fragments of people lives.” The items come from the collection of Mark and Paula Callihan. Additionally, also on display are a number of tornado recovery posters created to benefit Joplin charity in the months that followed last year’s catastrophe. The Post Memorial Art Reference Library is located inside the Joplin Public Library.

Guest Piece: Leslie Simpson – Route 66: A Method to the Madness

I have always wondered why Route 66 took such a circuitous path through Joplin. Coming in on West Seventh, it made a sharp turn left onto Main, then headed east on First over the viaduct. It continued on Broadway, turning north on St. Louis; after crossing Turkey Creek, it took off at a 45-degree angle on Euclid. It went a couple of blocks on Florida, then right on Zora and left on Range Line. If it were not for the fact that Route 66 was built during Prohibition, one might wonder if the cartographers had been a little tipsy!

Recently I was looking at some old plat maps of Joplin, and I noticed something. The Southwest Missouri Electric Railway, an electric streetcar that was established in 1893 by Alfred H. Rogers, took an identical 45-degree angle after crossing Turkey Creek in its route from Joplin to Webb City, Carterville, Lakeside Park, Carthage and other points east. The trolley line angled through Royal Heights, a separate village that had incorporated in 1907. Eureka! This information may be common knowledge, but since I did not know about it, I was excited to figure it out on my own.

At its peak, the railway company operated a huge fleet of streetcars and 94 miles of tracks in three states. But its days were numbered. As private ownership of motor vehicles increased, railway patronage dwindled. In 1925, the company began running passenger buses and phasing out its streetcars. The Joplin stretch of Route 66 was under construction from 1927 through 1932. After Royal Heights was annexed into the city of Joplin in 1929, the railway company removed the tracks through Royal Heights. The old track-bed was paved as Euclid and became part of the historic “Mother Road.”