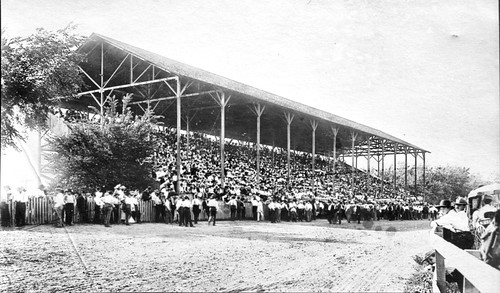

Edward Knell is credited with bringing the first “bred” race horse to Jasper County (as well the “art of embalming”) in 1889. The lucky equine was named “Ben McGregor” and cost Knell an estimated $3,000 dollars, quite the figure at the time. However, as early as 1872, even before Joplin came into existence, a race track was built just south of town that ran a half-mile long. Another race track was built in 1879, along with stables, an agricultural hall, and a grandstand. Gilbert Barbee, one time owner of the Joplin Globe, House of Lords, and Democratic party boss, bought this park and named it Barbee Park. The grandstand featured in both images was designed by Garstang & Rea for Gilbert Barbee’s “driving park” for a price of $6,500.

Barbee Park was home to countless horse races, but also served as the venue for such events like the Firemen’s Tournament that was held on the grounds in 1908. It was at the park where Joplinites got their first real glimpse of the speeding prowess of some of the first motorized fire engines in the nation, as well one of the last fire engine horse team races in the city’s history. Unfortunately for Barbee, in the middle of an April night in 1909, the grand stand caught fire and was a complete loss, despite the best efforts of Joplin’s fire department. The grand stand was never rebuilt and in the 1920s, Barbee’s son leveled the track area to develop a neighborhood.

As Joplin history expert Leslie Simpson writes in her book, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture, “He built the Barbee Court addition right on the old race course, preserving the graceful oval of elm trees that once surrounded it…The outline of the old race track can be traced by looping around from 17th to 19th Streets from Maiden Lane to the alley between Porter and Harlem Avenues.”