Despite the widespread fear of the “Yellow Peril,” not all Americans viewed their Chinese neighbors as economic competitors or sinister agents of the Chinese Emperor. It also helped if they were hard working Christians. Preston McGoodwin, a reporter for the Joplin Globe who went on to serve as U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela, profiled one of Joplin’s Chinese residents, Ah King.

King, owner of the Crystal Laundry located at 818 South Main Street, was lauded by McGoodwin as a “devout Christian worker.” He arrived in San Francisco, California, at the age of fourteen sometime around 1880. Although he did not tell McGoodwin how he ended up in the Midwest, he did relate that he arrived in Joplin in 1900 after living in nearby Springfield, Missouri. He reportedly astounded members of Joplin’s small Chinese community when he announced he was a devout Baptist. McGoodwin informed the Globe‘s readers that King “differs materially from the average church and association members in that he is at all times devout and intensely sincere.” McGoodwin also praised King for his “scrupulously clean” business that employed several white girls who washed and ironed customer’s clothes. King’s luck did not last.

A few months later, the Joplin Globe reported that Ah King and his brother Sam Long left town after he fell behind on rent to the Leonard Mercantile and Realty Company. It was noted that King had always borne an “excellent reputation” and was a “consistent member of the Baptist Church.” Joplin residents who knew King insisted he left to find money to pay his landlord, he left behind in his wake two angry female employees who were forced to wash and iron laundry to make up for their lost wages. “He owes us, the wretch,” one of the girls growled as she starched shirts. Her compatriot added, “It’s a perfect outrage to treat us girls so.” Others thought that King was spirited away by members of the Boxers, an anti-Western Chinese group, because he openly expressed his disapproval of the group. King did not return to Joplin.

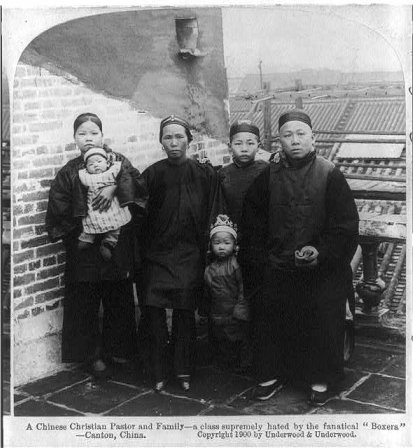

Chinese Christians, as pictured here, were detested by the Chinese Boxer Movement. This may have been why some believed the Boxers to be involved with King's disappearance.

Another one of the handful of Chinese residents in Joplin, Jung Sing, also experienced misfortune. Sing, who ran a “chop suey restaurant” on East Fifth Street, was arrested for selling opium. After he bonded out of jail, he returned home to find that his American wife had left him, taking his entire savings of $700. As Sing said (as crudely rendered by a Joplin Globe reporter), “She done skippee. When I fin’ she make getaway, I lookee in clash legister. All empty. Lookee in safe. Empty. I makee to fin’ out how much gone. Seven hundred dollar. I marry China gal next time.”

It was not the first time that Sing had had bad luck with women. After arriving in New York, he opened up a restaurant and married an American citizen. Together they lived in New York City’s Chinatown until one morning he woke up to find that she had disappeared. After searching their abode, he found she had taken $1000 of his money. Sing soon left for San Francisco where he met his second American wife. Together they moved to Joplin and lived there until she left with his money. When asked if he planned on catching her, Sing shook his head and said, “No, no. Makee no fuss. Never get seven hundred dollar back anyhow. Marry China gal next time.”

A chop suey restaurant in Chicago. Restaurants were always an option for immigrants seeking to find their place in a community, like Sing in Joplin.

Sing’s luck did not get any better. A few days later after his wife left him, two men came into his restaurant and refused to pay the bill. When Sing demanded they pay, the men attacked him. The proprietor ran to the back of his restaurant, grabbed a revolver, and chased the two men out onto the street. He fired two shots but failed to hit either man. After an investigation, Sing was arrested for disturbing the peace by Deputy Constable Norman Bricker. His fate is unknown, but one can hope that he found a wife who would not run off with his cash.

The experiences of Sing and King represent one more window into the world of Joplin’s Chinese immigrants. Did every immigrant come across similar bad luck or were our two migrants featured here the exception? Although historians cannot judge whether or not either man was truly accepted as a member of Joplin society, King may have been looked upon more favorably, as he was a devout Christian. Sing, on the other hand, may not have been as tolerated because he had been charged with selling opium and was married to a white woman during a time of great racial intolerance. Perhaps both men were fortunate enough to obtain their American dream far from the shores of the Celestial Kingdom.

Sources: Library of Congress, Joplin Globe.