Walter Williams, founder of the University of Missouri’s Journalism School, once wrote “Joplin is a city of self-made men, nearly every one of the moneyed citizens having made his fortune there. They are largely American born and American educated.” As Williams observed, Joplin was primarily populated by American citizens, but there were many immigrants who called Joplin home. Few, however, were Chinese.

Chinese immigrants arrived on America’s shores beginning in the late 1840s during the California Gold Rush. Two decades later, even larger numbers of Chinese laborers were recruited to work on the Transcontinental Railroad. The influx of cheap labor and threat of economic competition sparked racial animosity. Violent anti-Chinese riots broke out in several American cities, including Denver, Seattle, and Rock Springs, Wyoming. In 1882, in response to growing outrage over Chinese competition, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act suspended Chinese immigration to America for a period of ten years. Only those Chinese immigrants who arrived prior to the act’s passage were permitted to stay.

An illustration from "The Wasp" a magazine of San Francisco often noted for its virulent depictions of Chinese Immigrants. Available from the Library of Congress

At the turn of the century, both St. Louis and Kansas City were home to sizable Chinese communities but the Chinese presence in Joplin was less substantial. Historians can be stymied by gaps in the historical record. The earliest Joplin city directory to have survived the ravages of time dates to 1899, leaving a gap in the city’s history that ranges decades. Meanwhile, county histories often overlooked and ignored the presence and contributions of minorities. Although the state of Missouri attempted to collect birth and death records beginning in 1883, the effort failed until 1910, when the Missouri General Assembly passed a law making it mandatory for counties to record birth and death information. Few archival collections can boast of letters, diaries, and manuscripts from early Joplin, much less one kept by Chinese resident. Thus, it is often difficult to piece together the history of an immigrant group at the local level, especially if it was a particularly small immigrant group.

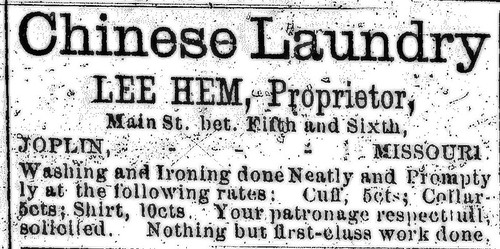

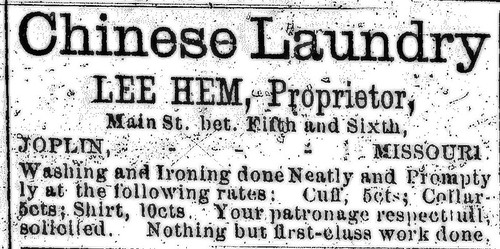

According to the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, there were no Chinese immigrants living in Joplin. By 1880, however, at least one Chinese immigrant called Joplin home. Lum Wong, a single twenty-seven year old native of China, listed his occupation as “servant — clerk in store.” He could not read or write English. Wong lived with sixty-four year old Jacob Wise, a retired merchant. A few years later, in1883, an advertisement appeared in the Joplin Daily Herald for a “Chinese Laundry” run by Lee Hem.

An advertisement for Hem's Chinese Laundry in Joplin

Although Lum Wong did not appear in the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, five other Chinese immigrants are listed as residents of Joplin. Most, if not all, worked in the laundry business. G. Goro, a thirty-six-year-old immigrant, lived on Main Street. According to the census, his neighbors described themselves gamblers, blacksmiths, day laborers, miners, and traveling salesmen. Sing See, Jung Jin, and Low Chung described themselves as “partners” in a laundry. See and Chung listed the year of their immigration as 1877 while Jin arrived in American in 1879. Thirty-four-year-old A. King, who roomed in a boarding house on Main Street, listed his occupation as “Chinese laundryman.” Unable to work in the mines, Chinese immigrants were forced to eke out their living in whatever industry was accessible, and often greatly restricted along racial lines.

Albert Cahn, a German-born clothing salesman who spoke at the opening of the Joplin Club in 1891 echoed the words of many American politicians when he declared, “This is the best apple country to be found and had Adam and Eve been placed here that Garden of Eden story would never have been told. We have vineyards here for the German, railroads for the sons of the Emerald Isle, commerce for the English, but no use for the Chinese.”

By 1910, only two Chinese immigrants lived in Joplin. One, Jung Low, gave his occupation as “Chinese laundry.” The other, John Jungyong, ran a restaurant.

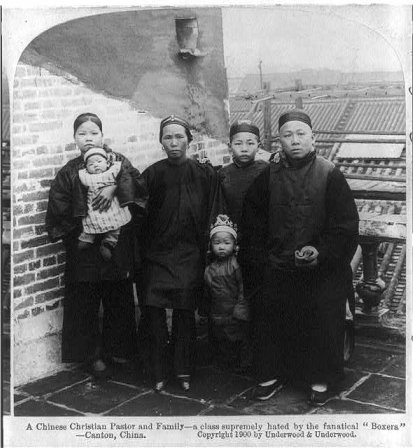

Within ten years, the Chinese population in Joplin grew when Toy Jung, an immigrant to America since 1890, opened a Chinese restaurant. Toy, the proprietor, was assisted in his business by a partner, Ling Kwong, who had reached the states five years after Toy. Additionally, five cousins of Toy worked as cooks and waiters. Only two of Toy’s cousins were born in California; Toy, his partner, and his three other cousins were all born in Canton, China. Another Chinese run business listed in 1920 was a laundry run by a Chinese-American named Charlie Hoplong.

The 1930 Census revealed the presence of another Chinese restaurant run by Shang Hai Lo, a sixty-year old restaurateur from Canton, China who had arrived from China the same year as Toy Jung. It also noted the absence of Charlie Hoplong and his laundry business. Four years later, Toy Jung, who had spent at least fourteen years in Joplin, passed away leaving only his wife Quong Jung to mourn his death.

Today there are a small number of Chinese residents in Joplin. If you want to sample some of the finest Chinese in the Midwest, stop by Empress Lion. This small, unassuming restaurant located in a strip mall at the corner of 32nd Street and Connecticut, offers some of the finest Chinese to be had. (We hope you’re well, Tiger and Lily!)

Sources: United States Census, “History of Jasper County and Its People” by Joel Livingston, and the Joplin Daily Herald, “The State of Missouri” by Walter Williams, and the Library of Congress.