The last few weeks have been scorching hot in southwest Missouri. In 1916, however, a sudden cloudburst wreaked havoc upon Joplin that seems almost unreal.

A “severe electrical storm” began at 10:30 at night with a host of giant storm clouds that hovered over the city until they burst and flooded the city below.

The deluge began with 5 and ¾ inches of rain during the night, followed by 5 and ½ inches within a two hour period in the morning. The rain was accompanied by a savage hailstorm that forced pedestrians to run for shelter. The downpour continued throughout the afternoon and in just a few minutes more than an inch of rain had fallen. Total rainfall was estimated at 6 9/10 to 7 inches. Long time Joplin residents remarked that it was the most severe storm the city had experienced.

According to C.W. Glover of 216 North Wall Street, the rainstorm was nothing compared to one that ravaged Joplin in July, 1875. According to Glover, it rained for three days and three nights. Joplin Creek, which divided East Joplin from West Joplin, became a raging torrent that no one dared cross. Professor William Hartman, a musician, and his wife were drowned, and several others were almost lost when seeking shelter or attempting to rescue those endangered by the flood waters. Joplin’s horse drawn trolley was unable to travel to Baxter Springs due to the washed out roads and streets.

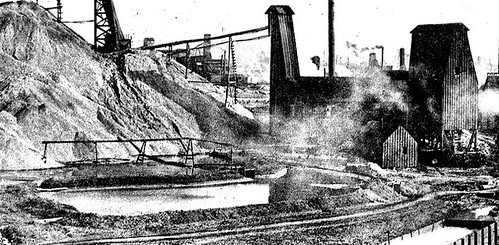

The 1916 storm was so sudden that it caught many people off guard. John Moore, Edward Poe, and Peter Adamson, miners working in the Coralbut (formerly the Quaker) mine west of Chitwood, were drowned when rainwater swept down into the mine at such a furious rate that they were unable to escape in time. Unfortunately for the three miners, the water had pooled at the top of the mine behind piles of debris that had formed an old mine pond when the debris gave way and a torrent of water flooded the mine shaft.

Altogether there were twelve men in the mine and they scrambled on top of some boulders as the water began to rise. The hoisterman at the surface lowered a tub to rescue them, but the water was so high and the current so strong that the men were reluctant to jump across the water into the tub. Nine of the miners were able to escape before the water overtook them. Moore, Poe, and Adamson said they could not swim and thought they would be safe on top of the boulders. It was not before long, though, that the hoisterman heard them call for help. One of them yelled, “For God’s sake, get a boat before we drown!” It was too late. They were unwilling to jump to the tub across the raging water and were drowned despite the efforts of their fellow miners to go down in the tub and try to reach them. The bodies of three men were not immediately located by rescuers.

One of the miners who escaped, Roy Clark, had been a sailor on a tramp steam freighter out of Queenstown. He declared after his harrowing experience that he was “through with mining.” Clark, who claimed he had developed strong swimming skills as a sailor, said he would not have dared to swim through the water that had flooded the mine. Another miner who had been in the mine, C.E. Evans, said he had warned his fellow workers about the storm. He said he had picked up hailstones as big as his thumb that had fallen into the mine and knew that trouble was not far off. By the time they saw the water pour in and ran for the boulders, he said, the water was up to their waists and rising. The tub, he said, was slow in coming. Evans’s fellow miner, Lowery, was standing on a boulder with water up to his chin when he was able to get to the tub.

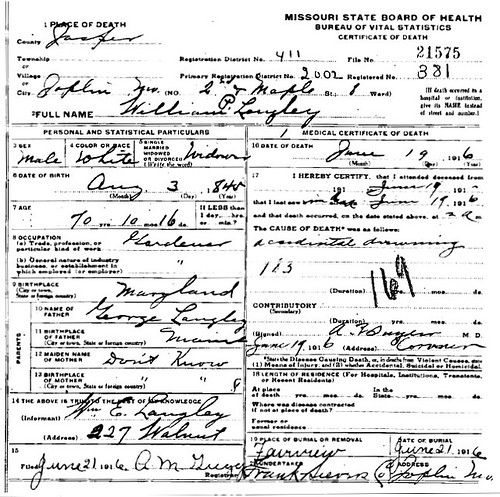

Even those who were in the safety of their own home were not shielded from the storm. William Langley, a 70 year old gardener, drowned in his home at Second and Ozark streets when it was submerged by water due to the home being situated next to a steep draw that funneled water down into the house.

When rescuers broke into Langley’s home, they found that the water had been only six inches from the ceiling. Some families in Chitwood sought refuge on top of their homes as the water began to rise, while others remained in storm shelters, still afraid to venture out due to the lightning and hail of the past few hours.

Mines suffered damage. The Grace Mine mill, located a mile north of Chitwood, and the Longfellow school building were both hit by lightning. Mine owner W.H. Gross of 318 West Eighth Street estimated damages at $15,000. Several other mine buildings were struck by lightning but did not burn. Many more were filled with water and required large pumps to remove the water. Total damages for mines across the Joplin area were estimated at $200,000.

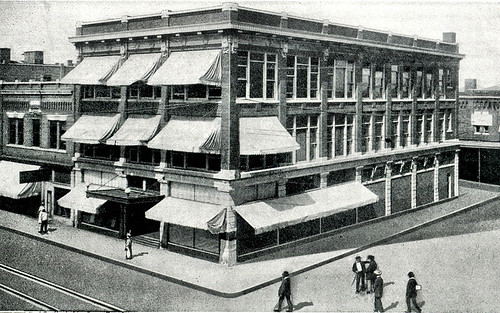

The storm of 1916 caused severe damage to downtown Joplin. Main Street from Fourth to Sixth streets was a “white-capped torrent for more than two hours” with a depth of two to five feet deep in some places. Businesses along this section of downtown reported losses of $100,000. Fleischaker Dry Goods, Christman’s, and Ramsay’s suffered severe flood damage. Ramsay’s lost all of the merchandise stored in the building’s basement which was filled with six feet of water at one point. Christman’s reported $10,000 in losses. Merchandise located on the lower shelves of the stores was thoroughly soaked.

One odd occurrence was when a bolt of lightning struck two wax figures in the Menard Store located at 423 Main Street. One of the figures was completely melted while the other was only scorched on the arm.

At the Commercial billiard parlor at 521 Main Street, seven billiards tables were ruined. Not far down the street the Priscilla Dress Shop at 513 Main lost several expensive Parisian gowns valued at $3,000, artwork estimated to be worth $2,000, and $300 of electrical fixtures destroyed.

It seemed as if no business escaped the wrath of the storm. The Farrar-Stephens Auto Tire Company at 520 Joplin Street reported damages of $5,000 while Kresge 5 and 10 Store lost merchandise valued at $5,000. The Joplin Pittsburg Railway Company suffered $2,500 in losses. The Burke Cigar and Candy Store and the Electric Theater building only had $2,000 in damages. Even the vaunted House of Lords suffered $500 of damage.

Joplin’s Hello Girls found that the storm caused $10,000 worth of losses. Nearly 4,000 telephones were out of service after the rain stopped, almost half of Joplin’s total number of phones. Poles were down, wires severed, circuits dead, and fuses blown all over town. Long distance lines, however, received very little damage. Phone company officials considered it a miracle.

Bridges and roads were hit hard. At least two large bridges were washed out, including the Joplin and Pittsburg Railway Company bridge over Turkey Creek. Track was twisted and torn up and down the line. A “masonry bridge over Turkey Creek at Range Line” was supposed to have been totaled at a cost of $1,000. Trains from the Kansas City Southern, Frisco, and Missouri & North Arkansas railroads were unable to roll into Joplin.

One enterprising young man captured a bathtub that floated out of a plumbing shop and used it as a canoe to paddle through downtown. Others joined him in boats and canoes (undoubtedly those who enjoyed fishing on the Spring River) while others just waded into the torrential streams of water. Barrels, boards, and all sorts of other debris clogged the streets and alleys. Citizens worked to grab the debris before it smashed out store windows and created more damage.

Giant potholes waited to twist ankles for those who dared to walk through the muddy water. Motorists were asked by city officials to drive slowly lest they hit a pothole and total their cars. Sidewalks were washed out as were sections of wood block pavement from Main Street to the Frisco rail tracks. City parks were ravaged. A sewer main burst at the North Main street viaduct and created a health hazard.

Joplin was battered, but not broken. In time, debris was removed, mud swept away, and the ravages of nature relegated to memory.