“Business men in blackface can be more amusing than professionals, especially when they strike a happy medium between the elite and the ridiculous.”

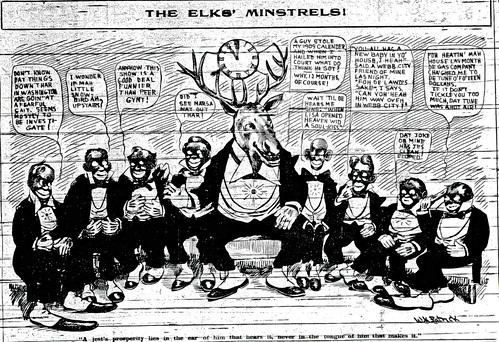

So began a review of the minstrel show put on by Joplin’s Elks Lodge, No. 501, in mid-January, 1909. Since the 19th Century, the minstrel show had been a steadfast form of entertainment based upon humiliating and stereotypical depictions of African Americans, often by white men with black makeup on their face. Generally, the performers adopted comical dialects exaggerated to effect laughter and ridicule. Entertainment in the shows ranged from comedy skits to song and dance.

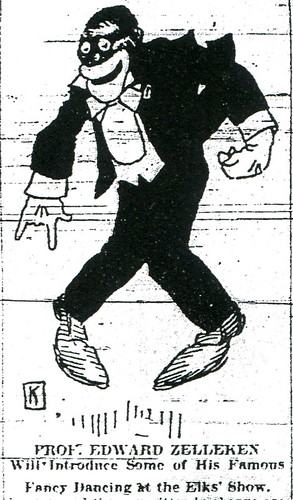

In an example of the acceptability of racism at the time in American and Joplin society, the minstrel show was produced by the Elks Lodge, a social organization of Joplin’s businessmen and reputable members of the city’s society. One advertisement for the minstrel show specifically noted the participation of Edward Zelleken, a member of one of Joplin’s most distinguished and wealthy families.

A small article that ran before the show promised an entertaining show and an opening which “should not be missed.” Tickets, the article claimed, were going fast, but good ones could still be reserved. An advertisement that ran near the article promised, “Ten Dollars’ Worth of Enjoyment For the Price of One.” The “Imperial Minstrels” as the Elks called their cast performed in the Club Theater. A follow up article the day after headlined, “Elks’ Minstrel Creates Furor Among Society” with the subtitle, “Business Men In Blackface Score Tremendous Hit.”

The jokes in the show ranged from the plain comedic to pokes and jabs at local businessmen, like the owner of Donehoo’s pharmacy, which was located at the busy intersection of 4th and Main. Other jokes were political in nature such as one about William Jennings Bryan recalled by a minstrel who claimed he had just stepped into an elevator in Chicago when he saw, “Mrs. William Jennings Bryan come running down the corridor waving her hand for the elevator operator to hold the car until she arrived. ‘You need not have hurried to catch the car,’ the elevator operator is said to have informed Mrs. Bryan, ‘I’d have waited for you.’ ‘Oh,’ replied the Commoner’s wife as she breathed heavily. ‘ I just wanted to show you that there was one member of the Bryan family who could keep in the running.’”

Another sign of the acceptability of the lampoon was the audience that turned out for the event. A reporter from the Joplin Globe described them, “Society turned out in all its finery to see something rich and rare…” Indeed, as the reporter noted, “And to a thousand, auditors giggled, laughed and te-heed until their faces ached while Joplin Lodge, No. 501. B.P.O. Elks, presented their Imperial Minstrels at the Club Theater last night.”

Source: Joplin Globe, 1909