The usual bustling noise of Joplin was interrupted one June morning by the unfamiliar buzzing of an eight cylinder airplane engine from several thousand feet above. It was not the first time that Joplin had been visited by an airplane, but neither was it a common occurrence, particularly due to the aviatrix at the plane’s helm. The pilot was the famous Ruth Bancroft Law and had been challenging both stereotypes and flying records for the past several years.

Her arrival in June, 1917, was intended to be promotional flight to drop “liberty bond bombs” over the city. All had begun well with a take off from Bartlesville approximately 110 miles away earlier that morning, but somewhere along the way, as she cruised in her modified Curtis airplane, one of the cylinders of her engine began to misfire. Concerned about the engine, Law opted to pass over the city once and then head for the landing strip setup for her on one of the links of the Oak Hill golf course. A crowd awaited her arrival, and she swooped down over their heads before she agilely set her plane down without incident around 11 am.

Immediately, the aviatrix was mobbed by fans who began an incessant volley of questions at the new arrival to Joplin. Law was described as dressed in “regulation army aviation uniform,” an outfit she later exchanged for a divided skirt, leather boots, and leather jacket. It was of particular note that she wore the uniform, as the United States began its venture into the war in Europe, Law had argued on the national level that women be allowed to join the military as aviators, a position that the government refused to adopt. She voiced her aspiration to the assembled crowd, “I have offered my services to the war department to be used in any way it thinks best.”

The Joplin Globe reporter on the scene wrote, “She talks distinctly, biting off her words with flashes of white teeth in a rather square little jaw. Her pronunciation is that of an easterner, or perhaps an Englishwoman. She talks fast, as she moves and does everything else.” Law continued on her aspiration to go across the pond to Europe, “I should like to go to France, but I don’t believe I would care for personal encounters in the air where the object would be to send one’s opponent hurtling to the ground in a mass of debris, mangled and perhaps killed.” She noted that the French had fine flying machines and her desire to fly one someday.

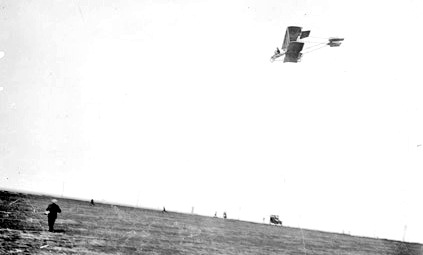

Law had planned to fly from Joplin to St. Louis, but the problem with her 100 horsepower engine effectively grounded the pioneer aviatrix. Instead, a special train car upon which her plane would be loaded, would be attached to the next Frisco train and hauled to St. Louis for maintenance. Law was not alone, but supported by one mechanic, two others, and a trusty French fighting dog. The plane, itself, was a bi-plane, but with the engine mounted behind an exposed cockpit. “The propeller blade is at the rear of the two main planes [wings] and is a monster thing compared with the rest of the machine. Made in one piece, it is nearly twelve feet from tip to tip.” The plane was a dirty yellow, streaked and smeared with oil from the engine. It was also a famous plane, as the pilot acknowledged it was the same that had flown the record breaking flight from Chicago to New York, a distance of nearly 600 miles.

The journalist described Law as possessing baby blue eyes, tawny yellow hair that often was kept under tight fitting headgear, and a satisfied smile that twisted the corners of her small mouth into delightful curves. From St. Louis, Law stated, she intended to fly to Chicago. When asked why she flew, the bold aviatrix stated, “I fly because I like to. I like the feel of the air and I like to do things that other girls can’t.”

Source: Joplin Globe, Chicago History Museum, Library of Congress