In the following story that we have presented in its entirety below, an anonymous Globe reporter writes in a florid style that one no longer finds in the pages of today’s newspapers. The article demonstrates a style of journalism that no longer exists as editors now demand clarity and conciseness, not flowery run-on sentences. One rarely thinks of the people who work the night shift, but as this article shows, little has changed since the turn of the century. We still rely upon the police, the fire department, security guards, janitors, and twenty-four hour fast food restaurants to look after us in the wee hours of the morning. And, as the reporter neglected to mention, far more women may have worked the night shift than he realized, only as soiled doves in Joplin’s red light district.

“In the hours of darkness, while thousands of Joplin people are wrapped tightly in the arms of Morpheus, hundreds of others are toiling for those who are unconscious of what is going on around them at that hour, keeping the big mill of life in one continuous grind.

It is not often that the average person gives a thought to those who are laboring during the hours of the night, after their daily toil is completed. Some hurry home to a hearty supper and a pleasant evening with the family, while others remain to enjoy a good production at the local theater or visit with a friend, but few of those think of others, who are at that very hour preparing to take their places and keep the great machinery of life well lubricated, so that it will run again the next day without a hitch.

It will be of extreme interest and will, no doubt, cause great surprise to thousands of Joplin people to know that more than 1,000 inhabitants of this city work throughout the entire night, besides there are hundreds of others who devote half the night to labor.

In its slumber the city must still be supplied with heat, light and water, its homes must be protected from fire, its streets and stores must be guarded and food for thirty-five thousand mouths must be prepared before the dawn. And all of this work and much more must fall to the lot of the toilers of darkness. Year in and year out, the city as a great workshop never rests period. While the day working people of Joplin are seeking relaxation, and while later hundreds of homes are quiet in slumber, a small army of tireless men and boys, and some cases women, is swaying back and forth in the nightly routine of their work, keeping up the great gind.

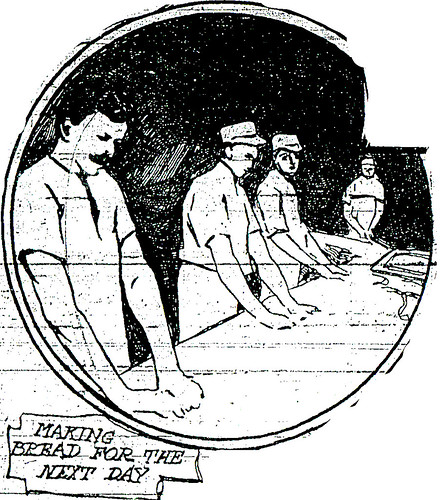

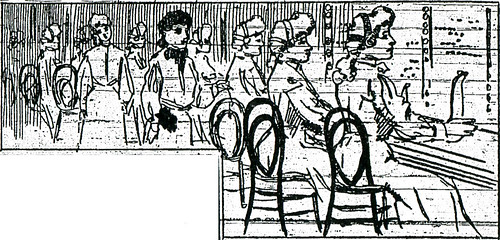

While thousands of Joplin people are sleeping, hundreds of miners are at work, bakers make bread for the slumberers to consume the next day; messengers boys hurry in every direction, firemen jump from their cots at the sound of the gong, ready to protect the sleepers from the ravages of fire; officers pace the streets in an effort to keep order; telephone girls are always on the alert to answer midnight call and hundreds of others stop only long enough to eat their midnight luncheon and then continue until dawn gives them the signal to retire.

Janitors and porters spend the weary hour of the night with their brushes and mops, preparing the hotel lobbies and business blocks for the next day’s work. Often times, these creatures are overworked, and they are helped in some cases by their wives, sisters and friends.

Night scenes among the railway employees are filled with variety. The hours of these night workmen are long, most of them coming on duty at 6:30 o’clock in the evening and working until that time in the morning. In the switching yards, the night visitor may see the most interesting side of railroading. In stations along the line, there are yard clerks, watchmen, roundhouse employees, car checkers and night operators. The Missouri Pacific employs a force of 15 men during the night. This includes a baggage man and operator at the passenger depot, yardmen and roundhouse employees, who are kept busy with the engines, keeping them clean and in repair. The Frisco employs 16 and the Kansas City Southern nearly as many.

In Joplin there are at least a half dozen restaurants kept open throughout the entire night. Waiters, cashiers, cooks and dishwashers have little time during these long hours for idleness. In the saloons, which are never closed until the lid smothers the lights early Sunday morning, there are at least two men — the bartender and the porter. Some places employ three men, and even four men during the night.

A large number of private watchmen work during the night. Almost every person knows of the 14 patrolmen who guard the city by night, few stop to think of the many, who, in factories and stores, tramp ceaseless, only stopping at intervals to rest. Some firms have old men for the work of watchmen, and others only employ young men. The work is lonely and the hours are long, and in many firms the watchmen are on a constant tramp. Next is the squad of regular officers, whose work is just as tiresome — but with much more variety perhaps, than that of the private watchmen. Some are patrolling gloomy alleys, while others are watching the stores and residences, always ready to defend the lives and possessions of their sleeping brothers.

Electricians may be summoned to fix broken wires. Often times they have to climb roofs and fire escapes [while the] working world is asleep, is an experience of unusual interest.

For a spectacular sight, one should visit a foundry. During the day it may be interesting, but at night when in dark and dangerous places, where only great care makes the feat possible.

To visit the industrial places of Joplin night, when a weird quietness hangs over the city, and the day-darkness settles over the city, the scene is one of splendor. At present, however, there are few foundries working night shifts.

Among the unceasing of the night are the dozen or more cab and baggage drivers of Joplin. It matters not whether the weather be warm or cold, rain or snow, these fellows go just the same.

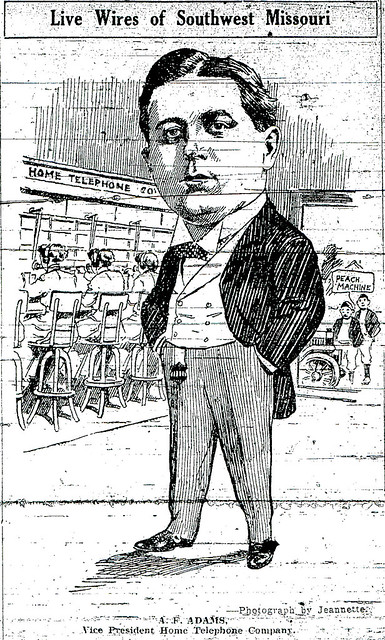

As near as can be estimate, there are thirty restaurant employees laboring during the entire night and about the same number at the hotels. The hotels employ a night clerk, one or two porters, as many bell boys, an engineer and sometimes a helper for the latter. From 20 to 25 saloon employees are at work, and in more than 100 concentrating mills, that operate at night, about 500 men tramp to and fro to their work as the sun rises and sets. Engineers, electricians and watchmen are kept busy at the lighting plants, there being about 12 in all. One postal clerk operates at the post office between the hours of six o’clock in the evening and four in the morning, when he is relieved. About six telephone girls remain at the boards from 10 o’clock at night until 6 in the following morning.

Three of the bakeries work night shifts, there being a score or more of breadmakers all told. 14 firemen stay ready to respond to their calls, and three telegraph operators at are at work in the Western Union and postal companies’ offices. Three or four messenger boys work throughout the entire night, and often times others are summoned to help the boys with their messages.

The Globe a force of 26 men, who all work until the grey hours of the morning. From 2 to 4 nurses are on the alert at St. John’s hospital. The Wells Fargo Express company employs two men during the night, and many others grind out their work night after night.

To give complete details about Joplin’s toilers of darkness would be almost an impossibility, but there is one other fact highly worthy of notice. While women have, to some extent, usurped the places of men in many occupations and callings of the day, the sterner sex has yet a monopoly on night work. Except for the telephone operators, there are few women night workers. It is estimated not more than 5% of the night workers are women.”

Source: Joplin Daily Globe