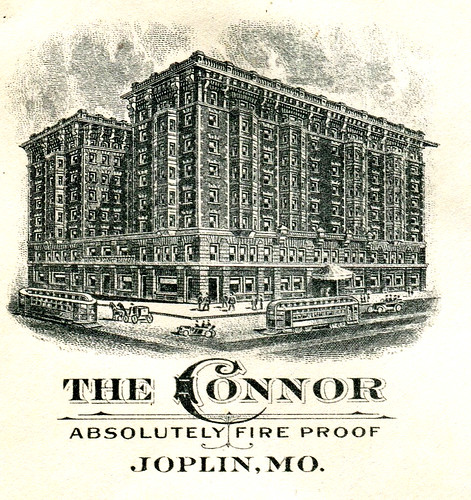

The Connor Hotel

On November 11, 1978, the Connor came crashing down. It had once symbolized the luxurious height of Joplin’s prosperity, but seventy years later, the Connor Hotel was singled out for demolition. Unwilling to have its fate dictated by dynamite, the Connor collapsed on its own and in the process trapped three men, two of whom died. The suspense of the search and rescue effort caught the attention of the nation and for one last time, the Connor Hotel made the headlines.

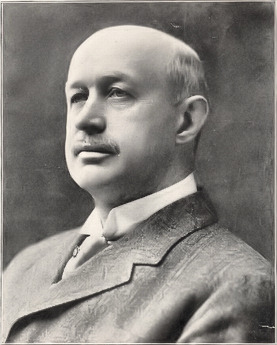

The Connor Hotel was the dream of Thomas Connor. In time, Historic Joplin will dedicate an entire entry to Connor, but for now a brief profile will suffice. Connor, the son of Irish immigrants, arrived in Joplin as a young man with little more than ambition and grit. A shrewd real estate developer, Connor’s wealth flowed from the lead and zinc mines, and became one of the city’s millionaires. His life and achievements were reflected in the life of Joplin as he played a considerable role in the city’s development and growth.

Thomas Connor

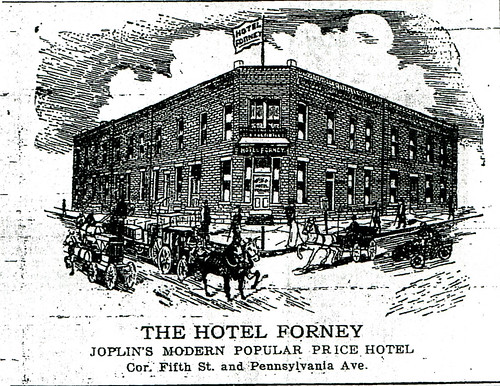

Among his many investments, Connor owned a significant interest in the Joplin Hotel, a three story structure situated on the northwest corner of the busy intersection of Main Street and Fourth Street. The Joplin Hotel, also known as the ‘Brick Hotel’ was built in 1874. It boasted fifty rooms that were constantly occupied by miners, capitalists, and traveling salesmen. Joel Livingston, an attorney and early resident of Joplin, recalled that the Joplin Hotel served as the hub of activity among powerful local politicians in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1893, one period newspaper reported that the Joplin Hotel planned to add a fourth floor. Thomas Connor, however, had grander ambitions. In 1906, Connor ordered that the Joplin Hotel be demolished in order to make room for a new building.

Work on a new structure began shortly after the Joplin Hotel was torn down. Connor shared his vision with the people of Joplin. Plans for the “New Joplin Hotel” revealed an ambitious design, one that would give rise to Joplin’s tallest building, one that would tower over Joplin’s then tallest building, the six story Keystone Hotel, which occupied the corner just across the street.

Connor employed the St. Louis architectural firm of Barnett, Haynes, and Barnett to design the Neo-Classical style structure. Work was then contracted to the local construction firm of Dieter and Wentzel. Building materials came from near and far. Steel for fireproofing and decorative ornamentation was brought in from the Des Moines Bridge and Iron Works of Iowa. The Spring River Stone Company of nearby Carthage supplied the exterior stone. Italian marble, imported by the St. Louis Marble and Tile Company, was used in the lobby and added to the planned elegance of the hotel. A visitor entering the hotel would enter under a Roman canopy built of bronze and glass.

Architectual Plan for the new Joplin Hotel

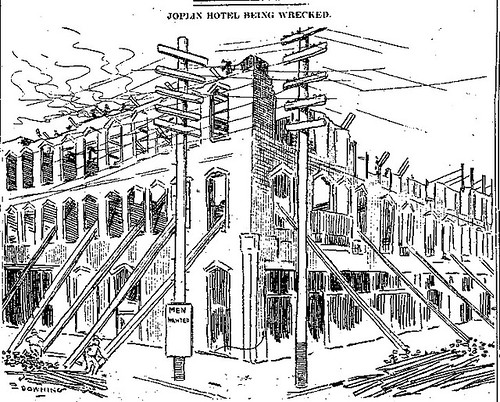

The new Joplin Hotel was unable to escape completion without incident or misfortune. The first notable accident occurred on September 26, 1906, when a 90 foot crane, used to lift the massive steel beams used in the construction of the hotel, collapsed without warning. Just after lunch, the crane was in the process of lifting a heavy beam from a pile situated on Fourth Street. To do so, the crane operator had to be careful that he raised it up and over the street’s telephone wires.

John Hively, a worker from Indiana, was riding on the beam as it was lifted into the sky. Hively and the beam he stood upon had risen over fifteen feet above the telephone cables when the five-eighths wire cable that held the weight of the beam snapped violently. The severed wire cable lashed out and struck the exterior of the Club Saloon across the street, “slicing through the weather boarding” for several feet like a knife. The severed crane wire then collapsed across the electrified trolley cables running down the street and the crane became “a mass of shooting sparks.” The crane’s metal cable finally settled on the street writhing dangerously with electric current from the trolley wires.

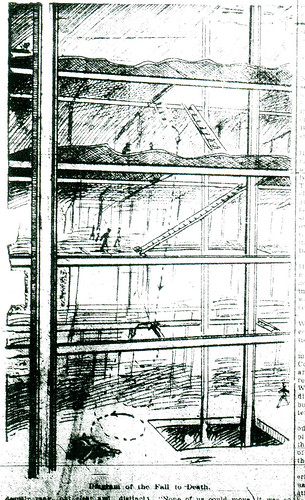

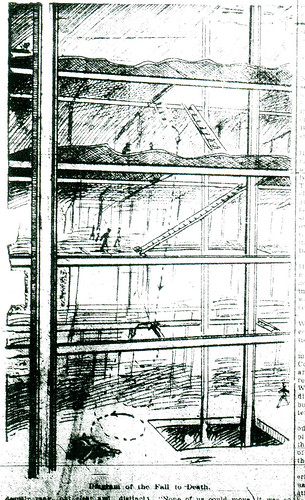

Illustration of John Hively's fatal accident

At the same time as the wire was causing havoc in its collapse, the heavy steel beam plummeted to the earth with Hively still on top of it and crashed onto the pile of beams below. Hively, as witnesses later recalled, landed in a seating position. He might have survived the incident had he not fallen backward from the force of the fall and hit the back of his head on the t-shaped end of another steel beam. His death was instantaneous, but may have been avoidable, as it was later reported that the crane had not been setup properly. His death was not the last.

By January 1907, five stories of the new hotel were completed. Irvin Neyhard, a thirty-five year old divorced father employed as a plumber’s helper, was one of many who found a job working on the building. Although he had first arrived in Joplin some seven to eight years earlier, he rented a room a nearby boarding house not far from the job site. Neyhard was killed when, while crossing the hotel’s elevator shaft on a wooden ladder on the fourth floor, the ladder broke. Neyhard plummeted more than forty feet and landed on a cement floor. His fellow workers reported that Neyhard frantically attempted to catch something, anything, as he fell through the air. He died a few minutes after hitting the ground.

Illustration of how Neyhard died.

Two months later another death made the headlines. Thomas Connor, Joplin’s generous benefactor, died while visiting a sanitarium in San Antonio, Texas. Only sixty years old, he had not even finished his first term as a state senator from Jasper County. The Joplin Daily Globe headlined Connor’s unexpected passing. The Globe’s editor suggested that the new hotel should be named after Connor. The public agreed and when the hotel opened up a year later in 1908, it was christened the Connor.

Advertisement for the opening of the Connor

The Connor Hotel officially opened Sunday, April 12, 1908, but had a soft opening a few days earlier. The evening meal, served at six o’clock, was not considered the official event to usher in a new era in Joplin’s history, but nevertheless was attended by Joplin society. Men wore their best formal evening attire while women wore elegant gowns and plumed hats. An orchestra serenaded the diners. The proprietors of the hotel, brothers Allen and D.J. Dean, were forced to turn away more than a hundred visitors who had hoped to dine at the Connor. Many more Joplin residents crowded the hotel to inspect the luxurious interior, though not before it was deemed safe that their shoes were not a threat to the hotel’s expensive carpets.

Allen J. Dean |

D.J. Dean |

The manager of the Connor was O.A. Reif, a long time employee of the Dean Brothers. Reif was assisted by Chief Clerk of the Connor, Sam B. Campbell. Campbell, in turn was aided by Carl Young, a former employee of the Keystone Hotel, and . The register, which was opened officially the day before, quickly filled up with fifty names, the first being C.V. Floyd, a traveling salesman from Chicago. By the end of the opening night, guests had contributed four more pages of signatures.

Due to Sunday laws, the Connor’s bar was not open that evening until midnight. Upon the chiming of the midnight hour, the doors to the Connor’s bar were thrown open, and the crowd swept into the room. The first to drink from the bar was A. Webber, the gentleman in charge of the installation of a refrigeration unit in the hotel. While enjoying his drink, Mr. Webber dropped a hundred dollar bill on the bar top to treat the rest of the guests to a round. It was promptly displayed on the bar’s mirror for all to see.

In order to ensure guest safety, there were only two entrances to the Connor, which the proprietors boasted protected guests from thieves. The main entrance featured a Roman canopy which led to the lobby which was graced by brilliant white marble columns. The lobby walls, which ran east to west, were lined with equally beautiful marble while the floors were covered in tinted tile. To the visitor’s right upon entering was a cigar and newsstand and the hotel office, replete with bronze and brass railings for the cashier and bookkeeper departments where visitors checked in. Elevators were also to the right. While not present opening night, a life sized oil painting of Thomas Connor was later placed on the north wall of the lobby near the office, a reminder of the man who envisioned the hotel.

Perhaps the most prominent feature of the Connor was the grand staircase located at the lobby’s west end. The steps, the balustrades, and railing were carved from the same fine marble of the lobby. Large glowing glass orbs encircled and supported by metal roses illuminated the steps. At the top of the steps, the stairway divided into opposing stairwells, one going up toward the north side of the building and the other the south. Both flights opened up to a fancifully decorated parlor on the next floor.

Interior of the Lobby

Back inside the lobby, spread throughout the long columned hall, were plush leather chairs and divans. Off of the lobby, by the office, was a seven chair barbershop, which boasted the finest barbers in Joplin, and in the basement, a billiards hall, the kitchen, and toilet rooms. There was little a visitor to Joplin, or a resident for that matter, could not enjoy or acquire within the walls of the Connor. The history of the Connor continued for another seventy years, one that includes growth, downturn and ultimately, tragedy; all of which will be covered in continuing coverage by Historic Joplin.

Street Level Photograph of the Connor's Fourth Street facade.

Photograph of Connor in a Joplin promotional booklet

Sources: Joplin Daily Globe, Joplin News Herald, University of Missouri : Digital Library, Historic Joplin Personal Collections