Catch up on the previous installments of the history of the Joplin Union Depot here: Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

Despite the progress made in December of 1910, work came to a sudden stop in the first week of January 1911 due to a snap of extreme cold weather. The approximate forty men at work on the depot building had to lay down their tools and watch the skies for better weather. The stop was short, however, and by the end of the month work was well on its way. 1/6th of the grading was left to be completed with only an estimated 25,000 yards of dirt remaining to be used to flatten the depot yards. Already 125,000 yards of fill dirt had been brought to the depot, mainly from cuts made by the Kansas City Southern between Joplin and Saginaw.

The hills and hollows of the Kansas City Bottoms were filled in or leveled off to create the needed flat surface for the depot's many tracks.

By the end of February, it was believed that the permanent track would soon be laid. At the start of March, the Joplin Daily Globe offered a glowing update on the Depot and at the same time, offered insight into how much the Depot meant to the people of Joplin. The paper elaborated on how a depot represents a city to the growing number of rail travelers, that in effect, the depot was the face of the community. The paper went on to describe the depot nearing completion:

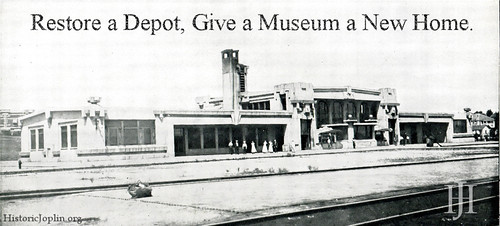

“Few residents of Joplin fully appreciate the magnitude of the new union passenger depot, now rapidly nearing completion at the corner of First and Main Streets. Its location at the foot of a gently sloping hill, some 100 yards from the intersection of the streets, combines with the style of its architecture to make it appear smaller than it really is.

The building is 300 feet long and 80 feet wide. These dimensions are more significant when it is remembered that 300 feet is the length of a city block….Built of reinforced concrete throughout, the depot is absolutely fireproof, and its walls are thick enough to bear the weight of several additional stories if they should be desired.

The interior of the building is provided with every convenience that has yet been devised for the benefit of the traveling public. The structure is divided into three general parts, north and south wings, each 60 feet long, and the central section, 180 feet long. The wings are of one story only, while the central part, in which will be located the ticket office, general waiting rooms and other apartments, is of two stories, with a rectangular opening in the second floor. The general arrangement of the depot is very much similar to that of the union depot in St. Louis, although the interior is more beautifully decorated than its larger counterpart.”

The article also noted the presence of more waiting rooms, lavatories, check rooms, ticket offices, and even a “great dining hall, 30 by 60 feet in extreme dimensions…” More so the paper proudly stated, “Nowhere in the country can there be found a depot site that offers greater opportunities for artistic effort.” The Globe wrapped up its article, “It is simply this — that when seven great railroads decide to spend a million dollars improving their facilities in a city, there must be something decidedly attractive about the city’s future…And Joplin will soon have an entirely new “face” to show strangers who ride the trains past her gates.”

At the same time, high ranking officials from the Santa Fe Railroad visited the depot site. A vice president of the company was quoted, “I have heard so much regarding the Joplin depot that I was anxious to see it…” The article noted that the vice-president was pleased with the depot, its progress, and its location, which would serve as a stop for the railroad on its way south to Arkansas.

The depot nearing completion in March, 1911.

The end of March raised expectations that the depot would be finished early. The filling of yards had been practically completed and work was underway for the installation of a round house approximately 100 yards northeast of the depot. The house would have three or four stalls, a “small affair” the Joplin News Herald noted before describing the turn table to be installed with it. The turn table, the paper described, “will bear up the largest engine that travels on any road in the United States.” Technologically advanced, the table would be turned by machinery, not by hand. Inside the depot building, meanwhile, carpenters were busy with wood work that was to have a “mission finish” and, “like the rest of the building, is artistic.”

“Let the eagle scream in Joplin,” announced a member of the City’s council in April, upon a motion to hold a celebration to recognize the completion of the Depot on the Fourth of July. In connection to the decision of the City Council, Mayor Jesse F. Osborne appointed a committee to work with the city’s Commercial Club on planning the gala. A ball, it was believed, should be held that night inside the depot with officials from every railroad invited to attend while a celebration at Cunningham Park earlier in the day to celebrate the nation’s anniversary. Curiously, an article on the matter refers that it was not the custom of the city, but surrounding cities, to hold such celebrations on the Fourth.

April did not pass without some mishap on the depot construction site. The first problem arose at the moment when the construction company believed the depot building virtually finished. It was then that they realized that either their construction or the design of the depot had failed to include space for the extremely important telegraph operators. As a result, two rooms were quickly added to either side of the ticket offices which required, “workmen…tearing out big slices from the side of the concrete structure…” These slices were not the last. It was not until this moment that it was discovered that the two big doors for the large baggage room had been built on the wrong side of the depot building. As a result, new doors had to be built into the building lest “teamsters would have been forced to risk their lives in driving over the railroad tracks at the east side of the depot.”

Hastily, doors had to be relocated from the south side of the depot to the north.

With construction otherwise subsiding, thought was finally given to the preparations of the grounds of the depot. The churned soil, “a sea of red clay, sticky as fish glue,” would soon be transformed into flower beds and grass plots. The excavation of the hill upon which Main Street was to the west and Broadway to the south had resulted in an area described as “great amphitheater” and an article bragged, “This land…will probably be used for a depot park…” and believed that no other depot in the country compared for its potential to be developed.

The depot otherwise constructed, the News Herald took time to praise the unique application of local materials in its building, primarily “flint and limestone tailings secured from waste piles of several Joplin zinc and lead producers.” Described as a “fitting monument to the successful efforts of the pioneers,” the concrete was deemed as hardy as a granite wall. The paper noted that while concrete had been used to great effect for sidewalks, curbs, retaining walls, dams, and culverts, it had never in Joplin’s history been used to such an extent in a building before the depot. Perhaps as motivation for future use, the article offered a recipe:

“Of the 22 parts in the concrete mixture used in constructing the station, 15 parts came from the Joplin mines, the exact formula being as follows: Mine tailings, 10 parts; Chitwood sand, 5 parts; River sand, 3 parts; Portland cement, 4 parts. Chitwood sand is the term used to describe the fine tailings from the sand jigs. In the mixture of the preparation for finishing the interior, the following formula is used: Portland cement, 2 parts; Chitwood sand, 2 parts; River sand, 1 part.”

The article noted that the best tailings for the project came from mines stratified with steel blue flint. The paper also reminded the reader of how much the Kansas City Bottoms had been transformed by the depot’s construction, “The new station is built on filled in ground in a district which was a waste of sluggish waters, dotted with dense growths of willows. For years this tract, of which 30 acres have been taken over by the Union Depot Co., was the city’s dumping ground. A sickly stream, carrying filth of every kind, crawled through the swamp. The Depot Co. has changed the course of this stream so that it no longer touches the station grounds. Hundreds of carloads of boulders and dirt have been used as filler.” Another, later article also extolled the depot which, “occupies a strip of filled in land that was an eyesore to the community for years. The building of the station and the filling in of the old swamp has converted a weed-grown bottom land into a beautiful valley, level as the floor of a dance hall. All the old swamps and marshes have been filled in, the course of Joplin creek changed so that it flows on the east side instead of the west side of the Kansas City Southern tracks, and when the grounds are finally finished and planted in blue grass, flowers and trees, they will be picturesque.” The landscape was forever changed and in the opinion of the people of Joplin, for the better.

By the end of construction of the Union Depot, much of the Kansas City Bottoms had been physically erased from the landscape of Jopin.

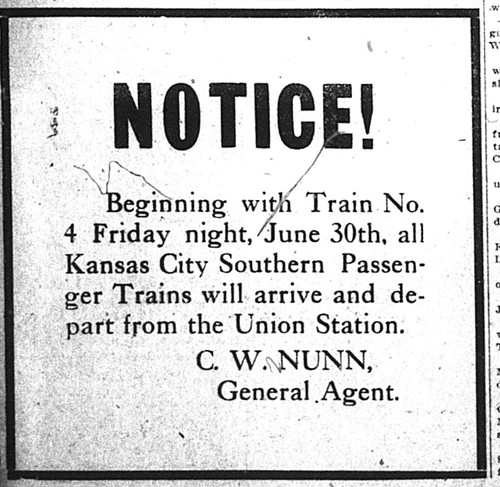

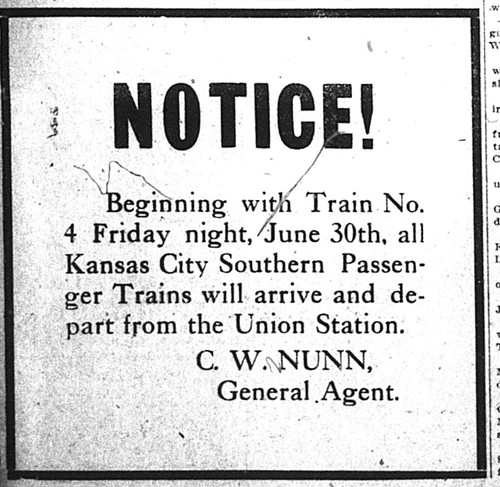

Then later in the month of May, the 19th, the first train was switched into the yards of the Depot, a string of work cars. Despite the presence of the cars, the Depot’s yards were not yet ready to receive passenger cars, and as officials quickly pointed out, the honor of “first train” is given to the first passenger train. The depot building was considered virtually complete, but contractors declared that the station would not be ready for a formal opening before July 1. The main work left to complete was the laying of permanent rails, and amazingly, still more grading work. Amongst the five railroads a growing rivalry had emerged to have the honor of the “first train” into the depot. A week later, the depot building itself was considered completed. By June 3, even the windows had been washed and the floors scrubbed and prepared for use. The woodwork had been completed and “the walls have received their last coat and the brass and iron railings fitted in position.” Depot officials bravely declared that the station would open on June 15. Four days before the set date, an announcement was made, “Unforeseen delays have been met in the track construction work,” stated the President of the Kansas City Southern, J.A. Edson, and that, “It would be impossible to properly complete the tracks and station before July 1.” Unsurprisingly, it was also mentioned that the depot building itself still awaited its furnishings and fixtures that were on order. Some furnishings had arrived in the form of furniture for the lunch room, such as kitchen cabinets, tables, and a “huge gas range of the regular restaurant type.”

Regardless of the delay, fifteen officials from the various railroads behind the depot met at the Connor Hotel. The meeting was for the purpose of discussing the various contracts between the railroads and to discuss the details of the depot’s opening. Station appointees had been made in the previous two weeks. Shortly thereafter, it was reaffirmed that July 1st would be the opening day of the depot. Comically, over a week later, it was realized that the Santa Fe railroad would not have a train available to enter the depot until July 15. Accordingly, the official opening was postponed yet again to July 20. However, the depot would accept trains before then. In preparation for the celebration, former Missouri Governor David R. Francis was invited to be the guest speaker. And, like the continually shifting opening day, the invitation fell through when a telegram alerted the organizers of the celebration that Governor Francis had departed from St. Louis for the summer and would not return until fall.

Meanwhile, the Depot construction had spurred construction elsewhere. Across the street from the depot on Main Street three buildings were under various states of construction. J.C. Jackson was the owner of one and had erected a three story building at a cost of $20,000. It was hoped the lower two floors would be home to a restaurant and the third a hotel. On the north side of Jackson’s site, Charles W. Edwards owned a lot and planned to build a four story building. The excitement of new buildings was quickly to be overshadowed by an even more exciting event back across the street.

One of many ads placed by the railroads in the Joplin newspapers to alert travelers of the pending opening of the depot.

On the night of July 1, 1911, and under the “fiery salute” of “skyrockets and torpedoes,” the headlight of Missouri, Kansas & Texas railroad train No. 83 “flashed around the curve at the north end of the depot” and pulled into the Union Depot at 10:30 pm (“exactly on schedule time”). An engineer, perhaps P.J. Nagle, responded with a tug on the steam whistle which shrilled to the cheers of over 2,500 spectators. The Katy Railroad had secured the honor of being the first train into the union depot. Crowds of railroad officials mingled together and shared welcomes and congratulations, while Joplinites “extended cordial greetings to the crew and passengers of the epoch-making train.” An article conveyed the sensation of all present, “Everyone seemed to feel that he was personally concerned in the event and took a part in the celebration.”

The honor of the first tickets sold went to Mrs. A. McNabb, a wife of one of the depot telegraph operators, and then immediately after to H.A. Adams, a traveling salesman from Kanas City. The event of the first tickets, which began approximately at 11 o’clock on Friday night, was retold a day later by the News Herald, “Both were anxious to secure the first ticket, but Dave Joseph, ticket agent, with the wisdom of old King Solomon, divided the honors by passing out the two tickets at the same instant. He shoved one over the counter with his right hand, the other with his left.”

The day before the arrival the Depot had been a scene of organized chaos as depot employees and officials had moved into offices and set to work preparing for business. Amongst them were most likely employees of Brown Hotel & News Company, such as F.P. Leigh, the general manager, who was in charge of running the dining room and lunch counter. Leigh was also assisted by a “corps of pretty girls.” Meanwhile, the formal opening was currently set for July 20, still. The highly anticipated Fourth of July celebration had also failed to coalesce. Officials in charge of Cunningham Park had protested the planned use of the park and the City Council immediately had surrendered. Perhaps from unreported blow back, the park officials changed their minds, but the City Council’s chief proponent of the celebration, Councilman Phil Arnold, had resigned his place on the city’s planning committee and the idea of a Fourth of July celebration was unceremoniously set aside.

An important arrival at the Depot a week later was a new clock. The Globe described the Chicago made timepiece: “The clock is seven feet high and will be run by compressed air, which will be made by a motor power. It is said to be one of the finest clocks in any station in the west.” Surprisingly, the location of the clock had yet to be decided and so the “enormous timepiece” was left crated for at least a day until the question of its location was decided. The main furniture had arrived a week before the arrival of the first train. A visitor to the Depot would have cast their gaze on beautiful Mission furniture described as such:

“…consignments of massive oak have already arrived and more is coming. This will be the heaviest and most attractive furniture in any depot in the Southwest…The lunch room has been furnished and is now waiting for the opening to begin work. It is fitted with an elliptical counter, at which can be seated nearly 200 persons. The table is covered with a heavy granite face, and the chairs are fitted with backs, and swing on a pivot…

In the office rooms desks of the mission style in dark oak are being placed in position…The furniture in the general waiting room is the first to attract attention. It is composed principally of heavy double settees, with high backs and heavy arms. These are also of the prevailing dark oak mission style, with the designating little double keystone which is in evidence in the architecture of the depot in all appropriate places.”

While preparations continued for the formal opening, such as the Missouri & Northern Arkansas planning special excursion trains to Joplin from as far as Seligman for the opening, other events were afoot. One such event was the visit to the Depot of the president of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Dutifully impressed, the president implied that his railroad may abandon their old Joplin depot in lieu of the impressive Union Depot Station.

Finally, at 2:30 pm on July 20, 1911, a parade of Joplin’s finest began under a drizzling rain from the intersection of 20th and Main Street. The procession was led by a vanguard of twenty mounted members of the Joplin Police Department with Joplin Police Chief Joe Myers and his assistant chief, Edward Portley at the front. Planned to follow, though not noted in an article printed afterward, were members of Joplin’s labor unions, secret societies, and civic societies. Among the noted was a procession of the city’s “fire automobiles” and more than thirty other automobiles set to carrying officials from the railroads. Members of the Commercial Club were present, as were four cars with members of the South Joplin Business Men’s Club and another with officers of the Villa Heights Booster Club.

At the depot, many sought shelter from the rain inside and around the depot, Mayor Jesse Osborne and Frank L. Yale, president of the Commercial Club, made speeches. Despite the wet summer day, Osborne spoke with enthusiasm of the depot’s construction, “The people of Joplin should congratulate themselves on securing even at this late day, a beautiful structure of this type. It is not only a monument to the progressiveness of the railroads entering this city, but it is a striking example of the uses to which a waste product may be put…” Yale followed Osborne and declared the depot impressive and the fulfillment of a “long felt want.”

From July 1, 1911 to November 4, 1969, the Union Depot served the city of Joplin. Over the fifty-eight year span, it was at the depot that Joplin saw her fathers, brothers and sons depart and hopefully return from two world wars. It was in the shade of the depot’s awnings that families bid farewell to friends and fellow family members who were departing for the wider world beyond Joplin’s city limits, and it was where they stood in eager anticipation for their return. For a city that foresaw Joplin as a great metropolis positioned at the intersection of the Great American Plains, the Southern Ozarks, and the Southwest, it was one more proud achievement to count among its others. It was one more step down a road to a brighter future.

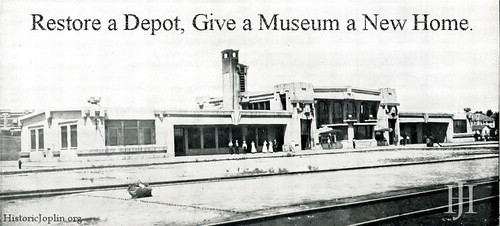

In the March of 1949, the Kansas City Southern showed off its latest liner, the Southern Belle at the depot. Just over twenty years later, it was the Southern Belle which pulled away, the final train to leave the Joplin Union Depot. The following decades of the Twentieth Century were turbulent for the former pride of Joplin. Only three years after its closing, the Depot’s first chance to become relevant again in the daily life of Joplin was lost when the City Council refused to renovate the building as a home to the Joplin Museum Complex in honor of the city’s 100th birthday. Not long after, the depot was added to the National Register of Historic Places, an honor, but not a safeguard against demolition.

The depot next was passed from one speculative buyer to another, each espousing plans to put the building to use which inevitably always failed to materialize. In the mid-1980’s, an attempt was made once again to renovate it, but it dissolved into lawsuits and accusations. Finally, in the late 1990’s, the Department of Natural Resources bought the site. It was not until approximately 2009 that for the first time the depot became the subject of serious discussion regarding renovation and restoration. In 2010, City Manager, Mark Rohr, proposed a plan to use the depot as part of a north Main Street development, possibly as a new home to the Joplin Museum Complex (JMC). Despite resistance from the boards overseeing the JMC, steps were taken toward this ultimate goal. However, at the start of 2012, such talk has been replaced by more important and pressing matters that arose in the aftermath of May, 2011. Until the time that they resume, the depot remains enclosed behind a chain link fence, waiting for a chance to once again become the pride of Joplin.