On April 23, 1940, a crowd of two hundred people stood on the train platform at Joplin’s Frisco Depot, awaiting the arrival of an important visitor to the city. Many of them would have identified themselves as union representatives, but their visitor was not famed labor leader John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers. Instead, when passengers began to disembark from the train, the individual who captured the crowd’s attention was a woman, often described by her contemporaries as “plain,” perhaps even ordinary looking. Plain and ordinary she was not. Frances Perkins, U.S. Secretary of Labor, was the first woman appointed to a position in the U.S. Cabinet. In response to the epidemic of “miner’s lung” in the Tri-State Mining District, Perkins convened a conference known as the Tri -State Silicosis Conference to allow concerned citizens, representatives from mining companies, government officials, and union representatives to discuss the issue.

Among those waiting at the platform to greet Perkins were Evan Just, secretary of the Tri-State Zinc and Lead Ore Producers Association; Frank Evans, president of the association; and the Reverend Cliff Titus, representing the Joplin Chamber of Commerce. Perkins then headed to the Connor Hotel where she stayed during the duration of the conference. She held a five minute press conference in which she stated that the purpose of her visit “is because you have silicosis there, and the labor department is concerned in preventing and correcting conditions due to silicosis.” After the press conference concluded, Secretary Perkins then headed outside to board a specially chartered bus. Together she and thirty other individuals representing various interests toured the mining district. Traveling out of Joplin on Route 66, she sat at the front of the bus with Tony McTeer, the district CIO president, and Evan Just. While driving past squalid miner’s shanties, Secretary Perkins remarked that something needed to be done to help those living in such dire circumstances.

The first stop was at the St. Louis Refining and Smelting Company’s Ballard Mine near Baxter Springs, Kansas. Secretary Perkins donned a “miner’s metal hat, raincoat, and overshoes” before she descended 350 feet into the mine where she then watched demonstrations of different mining methods. She was reportedly very interested in the “methods used by miners in drilling and in a dust control demonstration” given by Fred Netzeband, air hygiene engineer of the Tri-State Zinc and Lead Ore Producers Association. Secretary Perkins was later quoted by an observer as saying, “The world should know the true picture of methods being used in controlling and eliminating dust in the mines.”

After the demonstration, she then met with several of the miners, shook their hands, and listened to their views of the different methods used to control dust. Perkins was accompanied twenty other interested individuals, including Episcopal Bishop William Scarlett of St. Louis; the Reverend Charles Wilson of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in St. Louis; and Miss Elizabeth Wade White of New York. All three were members of the Tri-State Survey Committee. It was perhaps the one and only time that a bishop of any religious denomination toured one of the Tri-State District’s mines.

Secretary Perkins then visited Treece, Kansas, and Hockerville and Picher, Oklahoma to view housing conditions. In Treece, she visited the home of Mr. and Mrs. William Hannon. Hannon and two other former miners told Perkins that they suffering from silicosis and were unable to receive treatment. Hannon’s wife and four children also reportedly suffered from silicosis. She then met with six women, described as the widows of miners, who stated that they and their children were plagued by silicosis. Secretary Perkins’ bus did not stop in Hockerville and Picher, but she was reportedly able to view “slum conditions” in all three towns from her bus seat. She then returned to the Connor Hotel and prepared for the conference which began at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. The conference itself was held on the roof of the Connor.

The conference revealed a variety of attitudes. After making her opening remarks, Secretary Perkins was followed by the Reverend Cliff Titus. Titus, appearing as a “representative of the public,” declared that workers in the Tri-State Mining District were all white, not foreigners; and that “they are independent and prefer to choose their own methods of living.” He then continued “Many of our people prefer to live near chat piles because they want to spend their money on other things” like cars. But Titus acknowledged that “people of the district are willing and anxious to bring about better living conditions in the mine sections and will co-operate with state and federal agencies.”

Evan Just, secretary of the Tri-State Zinc and Lead Ore Producers Association, spoke on behalf of a majority of mine operators. He declared that operators had made great strides in reducing silicosis over the last several years. Just cited statistics that allegedly showed that incidences of silicosis in miners had been reduced from 60 percent in 1913 to 22 percent in 1929. Further progress, he claimed, had been in the years since. What Just failed to mention, however, is that this only applied to the large mining companies who could afford modern mining equipment, and not the smaller independent operators who could not. Just, however, denied that individuals could contract silicosis from surface dust.

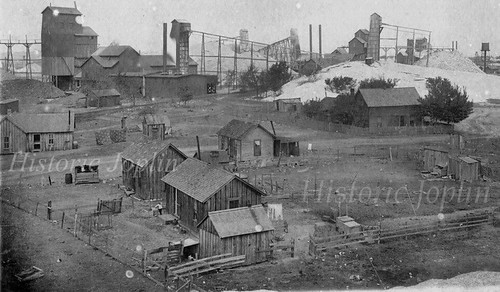

Miner shacks from the turn of the century - the condition of miners' homes continued to be poor decades later.

He then addressed living conditions in the Tri-State Mining District by stating that slum conditions were the result of social problems. “That many people who can afford better homes prefer to live in small, unpainted two and three-room shacks and spend their surplus funds on automobiles and radios cannot be charged against the mining industry,” Just maintained, although he claimed the mining industry did want to eliminate squalid living conditions. He was followed by representatives from federal and state public health, relief, and labor agencies. Even former Joplin resident Mrs. Emily Newell Blair, the noted political activist, was in attendance. Notably, former miner and the district CIO president, Tony McTeer, spoke in the interests of miners. He said, in part:

“Madam Secretary, ladies and gentlemen, conferences as such are not new to you, and to many people it is the usual approach to a problem, to sit down with all interested parties and discuss what is wrong in order to agree on a remedy. I can frankly tell you that a conference of this sort is new and different to the working people of the Tri-State area…

Some people believe that because the miners have not made a lot of noise about their troubles, because of the ignorance of themselves and others, that the workers have no troubles. That is not correct.

I am proud of our miners here. They know they have troubles aplenty, and what they are, but they also know false hopes when they see them. They have been fooled too often, so that now they don’t let themselves in for another deception.

However, they also know a good beginning when they see it. And this conference was received by the people of the Tri-State with great hope and anticipation of beneficial results…

We appreciate your coming this long distance, knowing that you would be convinced that here lies a serious problem.

Young men are dying. Ailing mothers and sick little children arouse in you the interest you have shown by being here today. Our district has the greatest percentage of widowhood in the United States; a sad commentary. These are the things that must be stopped for the future welfare of all the citizens who live here.

The problem as we see it is threefold. First, dust control; second, proper hospital facilities; third, adequate housing.

To reduce the high death rate among the miners requires better dust control and better working conditions in the mines. Stopping silicosis is one step in the direction of curbing the infection of tuberculosis. Mines today go in for more mechanical equipment, as we are living in a world of progress. I haven’t myself worked in a mine for the last five years, but the mining conditions and the health of the miners are my business. Our people working in the mines today give many exact reports of what does on in the mines.

It is said that wet drilling has solved the problem of dust control.

There have been two general fields of mining in this district. First, what we term the old country, which is the Joplin, Webb City area. Second, the Oklahoma and Kansas mining district. In the Joplin district the drilling was done with the piston machine or dry drills. The water liner drilling machine was introduced into Oklahoma and Kansas fields in 1916 or 1917, and from around that period it has been used exclusively. I wish to speak from my own experiences on this. I have never worked in mines except where water-lined drills were used, and I have silicosis, or dust on my lungs. We can produce the names of hundreds of men who have never worked except under wet drilling conditions, and we have buried a great many of them. I have prepared a list of some of those men who I know have died. I am turning it, with my statement, over to the chairman of this meeting.

Since wet drilling alone does not solve the problem, the problem still is dust control. We must get at the root of the problem…”

At the end of the conference, the Tri-State Survey Committee of New York sponsored a showing of “Men and Dust,” a short documentary film by noted photographer Sheldon Dick. Dick had journeyed to the Tri-State Mining District to illustrate the impact of silicosis on the lives of area miners and their families. It was Dick who famously dubbed Treece, Kansas’s Main Street as the “street of walking death.” An estimated one hundred people stayed to watch the film in the Connor Hotel’s Empire Room. Evan Just decried the sixteen and a half minute film as a “smear campaign” against the mining district and the companies that operated there.

After twelve hours, Secretary Perkins was scheduled to leave Joplin to return east. She announced that she would “appoint in the near future a committee of representatives of the three states to explore the possibilities of perfecting a ‘state compact agreement’ for coordinating the work of concerned authorities and agencies.”

Before leaving, she spoke to a crowd of 700 to 800 people at an open labor meeting sponsored by the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers and the American Federation of Labor. Her speech focused on the need to improve housing and living conditions in the mining district. After concluding her remarks, Secretary Perkins then left to catch her train.

As David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz point out in their book, Deadly Dust, the issue of silicosis faded away because of the lack of a strong labor movement to press for better working and living conditions, and the subsequent collapse of the mining industry in the Tri-State region. After the death of FDR, subsequent administrations had little concern for miner’s lung. But for a brief period of time, Joplin and the rest of mining district captured the attention of the nation

Sources:Joplin Globe Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the On-Going Struggle to Protect Workers’ Health by David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz “What You Really Want Is an Autopsy”: Frances Perkins and the U. S. Government Conference in Joplin, Missouri, 1940 http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/128/