Catch up on the previous installments of a History of the Joplin Union Depot with Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

By mid-August a concrete mixer had been put to work at the site of the depot. The concrete it produced was immediately used to build piers sunk into the earth upon which the rest of the foundation and depot structure was to be supported. The workers, twenty teams in all, enjoyed unsually cool weather and as a result, progress delayed by earlier heat, pushed forward rapidly. Placed about the construction area were multiple piles of gravel, lumber and other construction material. Despite the mostly finished job of leveling the Kansas City Bottoms, the actual depot site was still undergoing a lowering of high places and a raising of low places.

Officials were optimistic over the progress being made throughout the month of August and “expressed every confidence of its [the depot] completion before midwinter.” Indeed, as smooth as the work had become, the depot was expected to be completed by the spring of 1911. All seemed to be in place, the material, and ever more men, Joplin men, the papers noted, were being hired. The laying of the corner stone was estimated to happen at the start of October.

At the same time, not far from the construction site, a Kansas City Southern engine and flat car were put to use in laying down tracks for the new rail yard. The track laying continued elsewhere with spurs built that extended to Broadway, as well to the electric railway that linked to the trolley systems of Joplin and Southwest Missouri. Another train put to work in the construction phase was made up of ten “dump cars” pulled by “the latest types of heavy locomotives.” A newspaper described the process, “Train, engines and all were put to work at once hauling dirt from the steam shovel, working southeast of town to the site of the yards.” At the yards, the soil was used to permanently flatten out the area of the tracks. As with the depot, itself, everything was progressing quickly.

The process continued into September. The location southeast of town, identified now as Saginaw, continued to supply dirt for the yards in trip after trip by the dump cars. The supplied dirt was then driven over by an engine leveler to flatten it further. The yards also demanded other sacrifices of the land, as a bluff just south of a North Main Street bridge was dynamited on a daily basis to make room for further yard space. By the 6th of September, the bluff was gone, as well numerous trees, shrubs, and odd pieces of trash, cleaned from the Bottom space between Main Street and the Kansas City Southern tracks. Thus, it was a surprise a few days later when at 8 AM on a Friday morning, the entirety of the carpentry crew, twenty-eight men in all, walked off the job.

The strike was in reaction to the failure of the contractors to hire union hod carriers. Hod carriers had the specific task of carrying supplies to bricklayers, plasterers, and other similar jobs around a construction site. Prior to the start of construction, an agreement, likely informal, had been made to use only union men on the building of the depot, itself. The carpenters, who had “quietly laid down their hammers and tools and quit the building,” were members of the Building Trades Council. Rumors were gossiped that the contractors intended to have an “open” shop at the depot site, the intention to hire non-union men, and therefore, avoid having to follow the regulations and rules that local unions demanded. The contractors, meanwhile, claimed that there were simply not enough union hod carriers available due to other construction efforts in Joplin.

A photograph of a hod carrier from the Library of Congress. These men played the important role of transporting required building materials to the craftsmen.

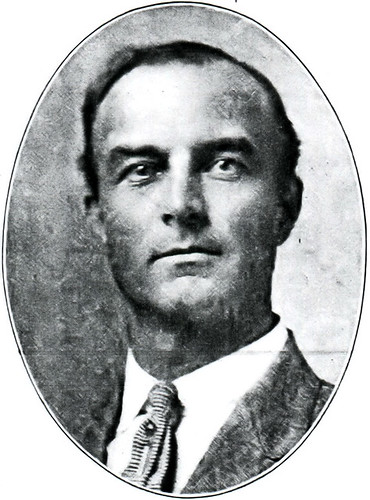

The head of the union’s local chapter, Albert H. Monteith, stated, “When the carpenters went to work on the depot it was their understanding that the whole job would be unionized…we went to work on this job a little over two weeks ago, well aware of the fact that some non-union labor was being used, but we were under the impression that our contentions would be met without delay and we would have as fellow workmen nothing but union men.” Monteith went on to add of the superintendent of the build, “[he] knew what action would take if he failed to take steps toward unionizing the whole job, and we gave him nearly three weeks in which to do his part, but when it became evident today that he would not recognize the union hod-carriers and other union building laborers, we quit.”

Monteith noted that union men were used at other construction sites of the Manhattan Construction Company, and if needed, they would undoubtedly strike in support of their Joplin brethren. The seriousness of the strike was great enough to stir rumors that the president of the company himself, President Looman, was on a train for Joplin to speak with the union men. If the president of the company visited Joplin, the papers failed to note his coming and going, but the strike did end approximately a week after it began. The resolution arrived when both parties came together and agreed that the conflict was in essence, a misunderstanding. The work reserved for union men would be reserved for union men, and the work done by non-union men would be done by non-union men. The clock was turned back pre-strike and all efforts once again pushed toward the completion of the depot.

A sense of urgency to complete the depot before the partnership of railroads laid the last of their tracks into the depot area became stronger as September came to a conclusion. An article published at the time looked ahead to its completion and touched upon its future beauty, “The architecture is of the mission style, and when completed the depot undoubtedly will be one of the handsomest, as well as one of the most unique structures of the kind in the country.” Flower beds and grass were to be noted improvements for the space between the depot and the nearest street. Its construction, reinforced concrete, the paper claimed, “is considered better building material than steel.” By the end of October it was hoped that the carpenters who had recently gone on strike would be at work on the interior.

The depot since it's construction has always had one apparent tower, featured here. It may be the two towers described were upon completion formed into one larger tower.

October was also a time of great focus on the innovative use of reinforced concrete. The work of building with the new material had been virtually completed in the basement, as well the exterior walls of the ground and second floors. 30 to 40 days, it was claimed, would be all it would take to finish the cement work at the depot. 40 days later, the focus was no longer on the cement, but two “massive towers” being erected above the depot. The work, described as, “exceedingly dangerous” involved the raising of huge frameworks of scaffolding to ensure success. The construction of the depot at that point in November 1910 involved the labor of over 300 men.

Work continued uninterrupted through November and December until bitter winter weather brought construction to a sudden halt in the first week of 1911. In addition to cold weather, that January brought the annual special edition from the Joplin News Herald, which took time to extoll the construction of the depot. “Erection of $90,000 Union Depot Transforms Topography of Dreary Sweep of Land in Kansas City Bottoms,” read the headline along with a copy of the architect’s rendering of the depot from the year before. In its braggadocio of the depot’s transformation, the article offers a glimpse of how Joplin saw the Kansas City Bottoms:

“Union Depot construction in Joplin has brought great change to the topographical appearance of a big acreage that for years was a dreary waste of abandoned mining gouges and slimy flat lands, the mire of the swamps growing rank with weeds and vines. One of the first steps in the grading of the union depot grounds, consisting of about 30 acres, was to change the course of Joplin Creek, an ill-smelling drainage channel, that twisted through the rank undergrowth, marking a zone of desolation through the very heart of the big tract which since has been filled in hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of earth and rock…”

“…Here, in the early days — and even later — twinkled the crimson lights of a mining camp’s tenderloin. For years and years this portion of the city was notorious, but with the coming of the union depot, every house, every shack — dilapidated on the exterior, but gorgeously furnished on the inside — every landmark that would remind one of the free and easy epoch of Joplin’s “North End” have been eradicated.”

The article also offered a description of the new area and what it meant to Joplin:

“Today the lower portion of the union depot grounds, where the station, the sheds, the turntable and the shops will be located, is as level as a checker board and as red as an orange, the fresh red clay, when viewed from a distance, resembling a soft velvet rug of mammoth dimensions. The ground slopes upward to Main street on the west and to Broadway on the south…”

“Joplin can hardly realize that the union depot is at last a reality. For years the city had dreamed of a union depot, but it seemed an endless period before the first spadeful of earth was turned. Since work started, however, progress has been swift and a big force of workmen has been employed steadily. The ring of the hammer has been constant.”

And finally, a full description of the depot’s beauty and attributes:

“ The station proper, which is of old Roman type, antedating the classic style, is constructed of plain and re-enforced concrete throughout, with oak finish. The floors are of concrete, with plain and Terrazo finish. The walls and roof are of concrete, the exterior being finished with white Portland cement, stippled, which produces a very pleasing effect.

The main part of the building is occupied by the general waiting room, women’s and men’s, waiting room and ticket office. The structure is two stories in height. The north wing provides express and baggage room, the south wing being occupied by dining room and lunch and kitchen. All modern equipment is to be installed, and the station is to be ready for use within a few weeks, although the completion of the train sheds, the round house, and other structures and equipment will require a much longer time.”

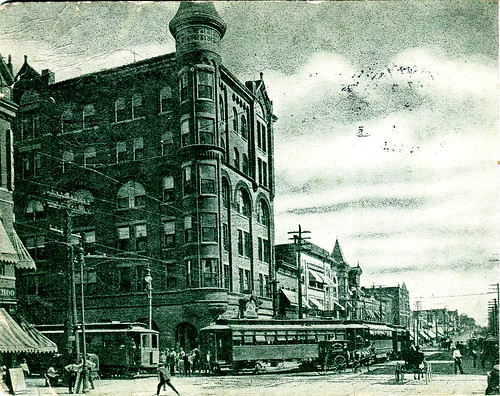

The future of the depot was bright in the first month of 1911 and the months ahead promised its completion. At the same time, Joplin continued its advancement as a city bursting with pride and progress.

Tune in for fifth and final installment of the history of the Joplin Union Depot in the near future!