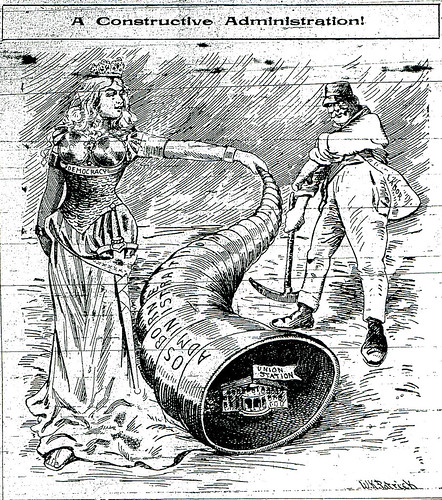

In the middle of October, 1908, the union depot franchise was up for debate before the Joplin City Council. The hope of John Scullin, a president of the Missouri and North Arkansas railroad, along with representatives of the Santa Fe railroad, was to bring the franchise to the City Council meeting on the night of Tuesday, October 13th. The intent was to have the franchise quickly passed. The Council, likewise, was prepared to request a clause be included in the contract which would force the Joplin Depot Company, which Scullin represented, to allow any railroad access to the depot so long as the facilities were available to accommodate such. The Council also hoped to convince the builders of the depot to help pay the costs of constructing viaducts for Broadway, Third Street, and “C” Street.

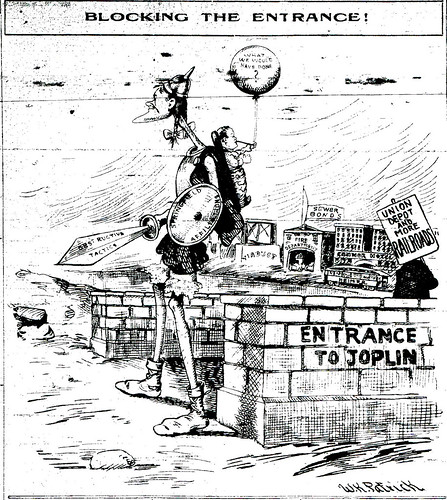

As the time for the arrival of Scullin and the Santa Fe representatives neared, the word was that the Joplin Depot Company officials had claimed that any provision in the franchisee that forced the company to admit other railroad companies would be unacceptable. Likewise, the franchise agreement said nothing about viaducts. A number of the city councilman also were not keen to the idea of one night of deliberation and passage of the franchise.

The afternoon of the meeting, Clay Gregory, a secretary of the Commercial Club, an organization composed of Joplin’s leading businessmen who worked to promote Joplin’s business interests, warned that one night would not be enough time to examine the details of the franchise. Especially, Gregory claimed, if the city allowed the Joplin Depot Company to retain the right to deny any other railroad access. The Joplin News Herald, unabashedly supported his position and wrote in accompanying bold lettering, “THE COUNCIL MAY BE GIVING AWAY THE LIBERTY OF THE CITY IF IT PASSES IT.” Gregory went on to doubt the certainty that if the franchise was given to the Missouri and North Arkansas and the Santa Fe, that it would mean that both railroads would build lines into Joplin. The article noted that a few months earlier, the Joplin and Eastern Kansas, a local branch of the proposed St. Louis and Oklahoma Southern, had been denied a franchise that had requested the same and likely for the purpose of cutting off Joplin from the Missouri and Northern Arkansas.

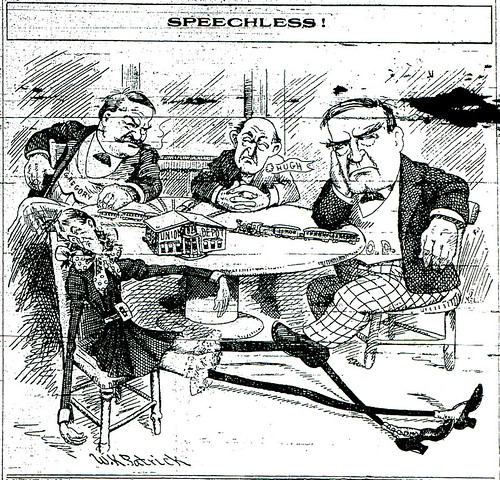

The franchise was not passed that night, instead the evening was composed mainly of agreements between representatives of the Missouri and Northern Arkansas, the Kansas City Southern, and Santa Fe, and the city council members on a franchise committee. The meeting was held at the Connor hotel and seemed at first to achieve everything that the city wanted before the earlier proposed vote on the franchise. The agreements consisted of the Joplin Depot Company paying for one third of the costs of the Broadway viaduct, as well any costs incurred from changing the plans of the Third street viaduct, and right to build over any ground owned by the company to construct the “C” street viaduct.

Also gained was a promise to allow other railroads into the depot and inserted into the franchise agreement an arbitration clause, considered a “liberal” contract element to the agreement. In exchange, the city was given the rights over the streets and alleyways that ran through the property it had already purchased two years earlier in advance of pushing for the passage of the franchise. The Santa Fe additionally promised that construction would begin shortly on extending the railroad’s tracks from nearby Pittsburg to Joplin. Likewise, the Missouri and Northern Arkansas noted that only eight miles remained to complete the line to Joplin. All together, the completion of the tracks promised to allow trains passage from New Orleans to as far as the great Northwest.

The franchise committee, headed by councilman N.H. Kelso, initially had some worries, though later he remained quiet upon the final vote. Kelso also participated in the discussion of the franchise committee of Joplin’s Commercial Club. Of immediate concern of the franchise was language in the franchise agreement, “…and provided the reasonable facilities of said depot company shall admit thereof.”

Chief among those worried was councilman Guy T. Humes, a future mayor of Joplin, who actively sought to prevent a vote from being taken, despite Scullin arguments. “I came to Joplin two years ago,” stated Scullin to the franchise committee, “and made the land purchases we now hold. We bought them to be ready when we needed terminals…Now we want the terminals.” The president of the Missouri and Northern Arkansas went on to sourly grumble, “I think I made a mistake in not asking you for something when I came here. You would have appreciated us better. We think we have presented a fair ordinance and we don’t think we should be asked for anything more. The railroads are hard up. Money is difficult to get.” Scullin then threatened, “As far as we are concerned, though, I can tell you we’re not going to be held up.”

The clause, detractors argued, could be used by the operators of the depot to prevent the admittance of other railroads into the depot. Thus, one railroad company, as a member of the Joplin Depot Company, might possibly use the excuse that the depot’s facilities could not reasonable sustain any new railroads as a means to keep out its competitor. Another element that worried some was the use of the word “continuously” in a clause stating that construction, once it began, should continue until completion. At the time, the fear was that if the company building the depot paused for a few weeks, the franchise would be lost. The City Council opted to discuss the matter on Tuesday, October 20th, while the Commercial Club chose to discuss the matter on Sunday, the 18th.

Humes, meanwhile, argued, “The wording contains to me a danger to the city’s future. We all know how the city is encircled by railroad tracks, and how the granting of this franchise means the giving away of practically all the remaining terminal grounds in the city.” Humes was worried that the franchise might give the Joplin Depot Company a terminal trust, “I may be wrong, but as I see it, it gives the railroad company absolute dictation as to what roads shall or shall not use the depot yards.” The councilman went on to loudly question, “Who is to determine what constitutes the ‘reasonable facilities’ of the depot and yards? Who is to interfere when the company says to a road that wants to come in here that the full facilities of the depot and yards are taken up, and that they can’t come in?”

As the time neared for the Commercial Club to meet and discuss the nicknamed Scullin Franchise, the reported local sentiment was that the council intended to vote for passage of the franchise regardless of the Commercial Club’s opinion. Other issues rose to join the controversy of the so-called “Joker” clause, which concerned the depot company allowing other railroads access to the depot. One issue was whether the clause in question clause would be available to be discussed under the “liberal” arbitration clause. Another issue was the potential cost of the depot and the worry that the depot would not be built large enough to keep up with the city’s progress. Scullin assured the city council the depot would be “$40,000,” to which the city’s response was, “If he really expects to spend that much money it won’t hurt him, and the city will be protected.” The actual cost of the depot would be much higher.

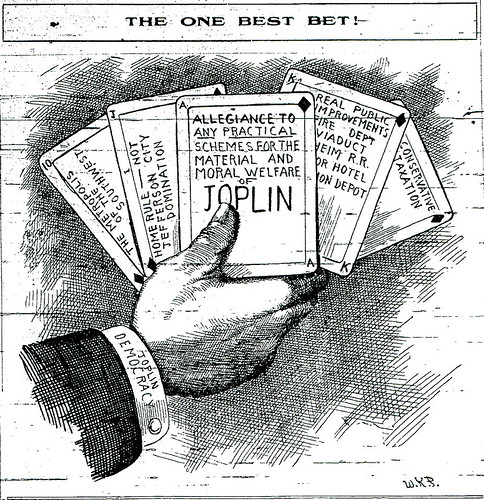

After a meeting dedicated to examining the Scullin franchise, the Commercial Club, led by its secretary, Clay Gregory, voiced strong disapproval for any rushed vote on the franchise. Most of the worrisome issues raised by Humes and other detractors to immediate passage, was voiced by the Commercial Club. The meeting, described as a rapid cross-fire between the proponents and detractors, consisted of points raised, refuted or confirmed one after another. In lead of the passage was Councilman Kelso whose concerns from before were satisfied and voiced the opinion that immediate affirmation was necessary, since the railroads “mean business” and warranted less than “mature” examination of the franchise.

The two sides argued back and forth. Proponents argued the city had received everything it desired from the Joplin Union Depot Company without giving anything. Detractors quickly pointed out that the city had conceded approximately $100,000 in vacated land and any other means to access the center of town would otherwise come at a much higher price. Likewise, detractors worried that the Kansas City Bottoms, the proposed location of the depot, was too small and would inhabit future growth. Proponents pointed out the railyards of Kansas City, which while small, were plenty large enough. Humes, who was present, worried about the absence of language controlling the regulation of switching and terminal charges at the depot and later introduced an amendment that would allow the city oversight.

By the end of the meeting between the city franchise committee and the Commercial Club’s franchise committee, only three strong points of contention existed. First was the existence of a perpetual life clause for the franchise, which the club wanted reduced to 99 years. Second, the addition of a clause demanding that construction of the depot commence within 2 years, which the city council committee refused to consider. Third, the injection of a forfeiture clause to penalize the union depot company for failure to carry out the contract, another clause the city council refused to consider.

As the city council moved to consider the Scullin franchise, the amount of vacated land was considerable. The value was estimated between $50,000 to $100,000 and consisted of three hundred and thirty-two thousand square feet of land, or more than 50 lots at 120 by 60 feet. The land, which would be transferred to the Joplin Union Depot company was at the time purportedly growing in value as factory land with individual lots selling between $2,000 and $3,000. In addition were sections of streets and alleyways that ranged from 1st to 4th streets, and Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Broadway.

Despite the protestations of Councilman Humes and the Commercial Club, the city council quickly moved to accept the franchise at their meeting on the 20th of October. As divided the Commercial Club and the city council were, so were the two city newspapers. The Joplin News Herald presented the city council vote as one forced by intimidation via a telegram from the railroads, and where the city “forgot” its promise to protect the business interests of the city. In contrast, the Joplin Globe trumpeted the passage of the franchise and dismissed as unimportant the concerns that had worried the franchise detractors. More so, the Globe ridiculed Humes and noted that the true detractor were not the News Herald, Humes, and the Commercial Club, but the St. Louis and San Francisco railroad, also known as the Frisco, headquarted in St. Louis, which used the councilman, the newspaper, and club, as mouthpieces to voice opposition against the passage of the franchise to the railroad’s rivals.

The passage of the franchise was done quickly by the city council. Presented by Kelso, the franchise was read three times, and then voted upon. Prior to the vote, Humes, joined by councilman Hennessy, refused to vote. Hennessy claimed he favored the franchise, just not the speed by which it was being processed. Hennessy, however, did not join Humes in the final vote, with Humes finding himself the odd man out of a 13 member vote. The Globe referred to Humes as “Honk! Honk! Humes” and described his reaction to the addition of minor changes to the franchise, “These miner changes were not enough to satisfy Honk! Honk! Honk! Humes, and he sprang out of his chair, and for several minutes waved his Commercial Club big stick over the head of the council. This amused the other twelve men who also represent the people of Joplin, but who do not represent the Commercial Club.”

The Globe continued, “They laughed at Humes, and the great reformer became angry, offered amendments, and made objections to he proceedings. The council and Mayor Osborne were in a good humor, and for once in his life, Humes was permitted to mangle all of the language with which he was familiar and kill all the time he wished.” The paper noted Humes was forced to beg for a second to his motion to propose an amendment, which was voted down. After which, the Globe stated, “Humes again made a noise like an auto horn,” where upon the council opted to continue its business “without paying further attention to the uplifter of morals of the entire world, and official representative of the Commercial Club.”

The News Herald offered a far more respectful review of Humes’ cautionary words (as well more of a blow for blow report of the meeting), presenting the councilman as offering a rational argument in opposition to an approving vote by the council. Humes, after the second reading of the franchise, reportedly arose and said, “It seems to me that the haste being displayed in pushing this franchise through is unseemly.” The News Herald described his words, “Mr. Humes continued, outlining his objections in the form of the franchise, calling the attention of the council to the absence of a forfeiture clause, the defective construction of certain sections, and the danger lurking in others.”

The paper also noted the behavior of the proponents amongst the council, particularly Councilman Molloy, whom the paper described as the master of ceremonies. “While Humes was speaking Councilman Molloy…sat glancing about, reassuring with a glance or giving an order by a sign. As Humes was about to close he turned to Councilmen King and Wells, and with an authoritative wave of his hands said, “Don’t answer him. Let it come to vote.” The councilmen obeyed.”

It was at this point in the discussion that Humes had proposed an amendment to attempt to fix the faults he and the Commercial Club perceived in the franchise. It was voted down. Hennessy, who eventually caved to the pro-franchise faction of the council, stood up to point out this was a rerun of another proposed franchise vote that had happened earlier in the year and had been voted down. Next to speak was Councilman Brown who firmly stated, “I have listened carefully to the reading of the ordinance and do not see anything wrong with it.”

The aforementioned Councilman King spoke next to explain away why no further attempt was being made with regard to the factors that concerned Humes and the Commercial Club, “We telegraphed to Kansas City this afternoon and asked them if they would accept the franchise without it [the contested clauses]. They answered positively no, so we reported the france with it in.” King went on to claim that the franchise had been before a city council committee for six months, to which Humes immediately interjected, “The franchise has not been before the committee but a week!”

The chairman of the Commercial Club, C. Newberger, also attempted to reason with the City Council and pointed out that St. Louis had made such a mistake. Newberger expounded on the problems with the franchise and declared, “You need not be afraid Mr. Scullin will not come here. He is a past master in the art of bluffing through franchises.” At this statement, it seemed Newberger had worn out his welcome, as Councilman Brown leapt to his feet and exclaimed, “Is the Commercial club running this city or is it the council doing it?” Newberger quickly responded he appeared only as a private citizen interested in Joplin. Tired yet of Newberger, Brown called for a point of order and had Mayor Jesse Osborne order Newberger from the floor.

In the wake of Newberger’s ejection from the floor, Councilman Hennessy inquired if a written contract existed yet between the Kansas City Southern and a promise to assist in the construction of the Third Street Viaduct. To this question, the city engineer, J. B. Hodgdon, piped up, “We have Mr. Rusk’s word for it.” The engineer continued, “If we vacate Third street to the depot company the Kansas City Southern will not be afraid of us.” Mayor Osborne chimed in, “That’s a point I want to know about.”

Finally, Councilman Molloy rose and spoke, “I’ll personally guarantee that the Kansas City Southern will take care of 338 feet of the viaduct.” The question of the aid for the viaduct caused a brief stir until the mayor promised, “I will veto the measure unless I get from the Kansas City Southern and the other two railroads in the union depot company, a written agreement that they will take care of 338 feet of the Third street viaduct.” The mayor continued, “An agreement to this effect must reach me within ten days.”

The council then voted for the franchise and the News Herald scathingly noted, “It is quite probable that not more than half of the councilmen who enacted the franchise ever read it. There was an evidence of ignorance concerning its provisions and its import last night that indicated this.” The paper, in contrast to the Globe, summarized the council vote not by what it had achieved, but how it had failed.

The next day the Commercial Club began what resulted in an extremely short lived campaign to persuade Mayor Osborne not to sign the franchise as passed by the City Council the night before. The Club expressed the same reasons which had been pushed by Humes and Newberger in the council meeting. Clay Gregory, already accustom to speaking out in the newspaper against the deal pointed out, “The Kansas City bottoms are the only feasible route of entry to Joplin.” Gregory then warned, “The franchise gives the union depot company control of this choice site,” the Commercial Club secretary then added, “As the franchise stands the city is helpless to enforce its provisions upon the company.”

The hopes of the club were dashed when city engineer Hodgdon reported a telephone call from Kansas City which assured the mayor that two of the railroads behind the depot company, the Kansas City Southern and Missouri & Northern Arkansas would help build the Third street viaduct. The Globe mocked the Commercial Club, “No-More-Railroads-for-Joplin organization,” and stated that prior to the telephone call, the Mayor had “listened with patience and courtesy” to it, something that most Joplin citizens would not bother doing. In fact, the paper claimed, “Many of the biggest property owners in the city have either laughed at the ridiculous objections preferred or have denounced them with indignation.”

Perhaps with the taste of immediate victory in the future, the Globe launched into a refutation of the worries of the naysayers. In addressing the question of the length of the franchise, be it perpetual or 99 years, the paper presciently wrote, “By the time another century, minus one year, has rolled around, the conditions in and about this city will have been transformed beyond the recognition of any of us alive today. This franchisee will have become an obsolete instrument, a yellow, faded document in the city’s archives.”

Refutations done, the Globe saved the last of its ink for what it perceived to be the power behind the main objectors, “James Campbell, esquire, king, crown prince, and owner of most of the kingdom acquired by the St. Louis Big Cinch.” Campbell, the Globe noted, contemplated building a depot for the Frisco to enhance his own land in the city, as well the railroad. The paper declared Campbell a “forceful personality” who exerted a “private car opulence” over certain citizens of Joplin. One such citizen was Clay Gregory.

“And yet Clay Gregory, secretary of the Commercial Club, who never did anything for Joplin until he got on the Commercial Club’s payroll, and has never done anything since excepting to draw his salary, who is now getting $150 a month from the Commercial Club for playing chess at the Elks Club, the money used to pay his salary being drawn from a trust fund which the Commercial Club directors have no moral right or expressed privileges to use for that purpose.” The Globe continued its scathing attack, “Gregory who was given the job of secretary because he was hard up and needed the salary, whose only achievement publicly has been to hang onto the job.” Of Gregory, the paper declared, “this fellow has the effrontery and gall to attempt to dictate to the city council and the mayor.” The Globe concluded of the Commercial Club, “has degenerated into the fat fatuousness of Clay Gregory…”

The paper finished with a declaration against the interests of the Frisco, “There are some things which this paper hopes to compel the Frisco to do. There is one thing that the citizens of Joplin don’t propose to allow the Frisco to do, and that is to keep other railroads out of Joplin and to tear down parts of this city which years of effort have built up in order to build up Jim Campbell’s individual interests.”

On October 26, 1908, Mayor Osborne signed the ordinance confirming the City Council’s passage of the franchise. Joplin was to have a Union Depot.

Source: Joplin Daily Globe, Joplin News Herald

Coming soon will be the next installment of a history of the Joplin Union Depot, beginning with the events surrounding Mayor Osborne’s signing of the ordinance and the long wait to the start of construction. Stay tuned!