On March 24th, 1901, visitors flooded into the newly opened home to the Joplin chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Association. Located at the intersection of Fourth and Virginia streets, the three story building was an achievement for the YMCA, if limited.

Established in February, 1891, the Joplin YMCA had 49 active members and 94 associated members. Elected as the first president was J.H. Dangerfield with C.H. Adams as his secretary. By its seventh year, the organization had opted to purchase and build a home for itself in Joplin in April of 1897. The selected site was the then location for the Haven Opera House, which sat on the northwest corner of Virginia and 4th Streets. For the near prime 4th and Main Street location, the YMCA paid $4,500 and allowed the opera house to continue operation until the end of the theatrical season. It was a necessary wait, as the YMCA did not yet have the funds to begin the construction of their new building. Nor did it believe it would raise such funds swiftly, as it entered into a contract to lease the property to the Studebaker Manufacturing Company.

The Joplin Globe stated at the time, “In purchasing the Haven opera house they have selected the best location in all the city for such a public building, and they have a nucleus of such a substantial nature that success is a foregone conclusion in securing the much needed new building.”

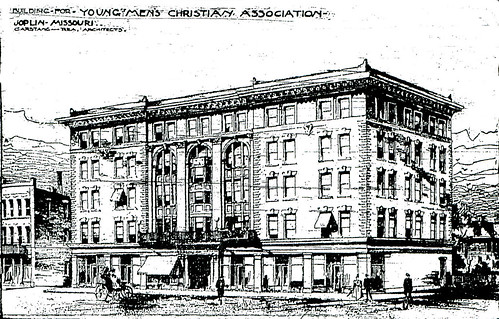

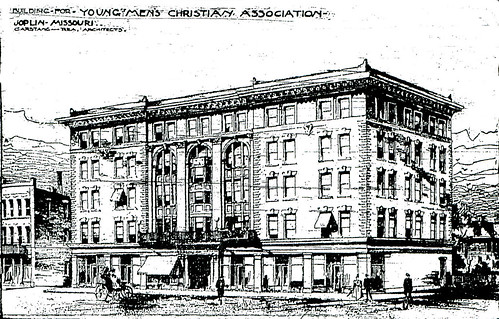

Gartang & Rea's plan for a 5 story YMCA building.

It was just shy of a year later that plans for the building were formally released for the public’s consumption. The Globe boasted of the proposed design, “The building will be large and costlier than any association building ever erected in a city the size of Joplin and will surpass in elegance an convenience most of those erected in cities of greater size. It will be, when completed, a splendid monument of Joplin enterprise and of its fostering care toward the young men of the city.”

The architects behind the design were Joplin architects Charles Edward Garstang and Alfred W. Rea, of Garstang & Rea. The men presented a five story building which was to feature a gymnasium located on the 4th floor with a ceiling which stretched up into the 5th floor where a viewing gallery was situated. Other proposed features were locker rooms for members and guests, as well as sleeping quarters, a camera room with dark room, a reading room, library, and a members and guests correspondent rooms. Not to be neglected, a small barbershop was also planned for the building.

Groundbreaking occurred on September 29, 1900, and at a cost of $150,000, the YMCA’s home was built, including the cost of furnishings. The aspirations of the YMCA had been restrained with only a three story building as the finished product. Never the less, the Globe commented, “If no religious fervor toward the uplifting and saving of young men’s souls fills your heart even then you will be proud of their quarters as a building and a credit to Joplin, for it is certainly a beautiful place.”

The article on the opening described a rotunda located at the top of a stairway which lead from the main entrance. The floor was tiled linoleum with dark wooden pillars about the room and chairs of the same color to match. To the right of the rotunda a parlour, and beyond it a kitchen and dining room. On the third floor, a visitor discovered another rotunda which offered access to a room dedicated for railroad men, as well a boy’s room for pastime and a game room for men. The men’s game room was equipped with checkers, chess, and a fireplace. White marble was used in the bathing apartments, which featured both plunge and shower bath arrangements.

The YMCA was not denied a large gymnasium, though instead of being found on a proposed fourth floor, was located on the second. It, too had a balcony for viewing on the third floor. Also on the third floor, was a stage, opera chairs, and space for meetings. Two stain glassed windows showered the stairway to the third floor in colored light, while a electronically controlled gate prevented access to the gymnasium to those who failed to possess bathing privileges (this was overseen by a watchful secretary and a button which raised or lowered the gate).

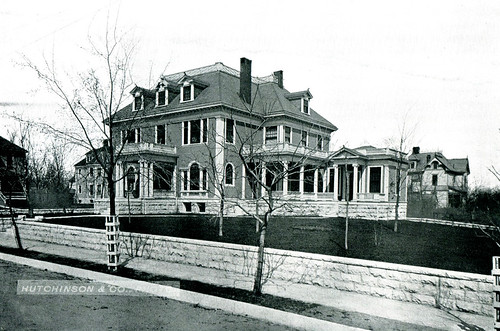

The home of the Joplin YMCA from 1901 to 1918. Note: Future owner, the Joplin Globe, is visible just around the corner on the right.

From 1901 to 1918, the building housed the YMCA until the organization built its current building on Wall Street (a future post will cover this building’s history). When it did so, it sold its former home to the Joplin Globe for $40,000, which promptly expanded from its original location into its neighbor.

Sources: Charles Gibbon’s “Angling in the Archives”, Missouri Digital Heritage, and the Joplin Globe.