Today’s update to the Architectural Legacy of Garstang & Rea series is the Junge Baking Company Cracker Factory building. The Junge Baking Company was once one of Joplin’s jewels of industry and it comes to no surprise to find that one of Joplin’s premier architectural firms was hired to help expand the factory. Built at a cost of approximately $16,000 in 1904, or the equivalent of near $372,074 in today’s dollars, it was part of a 1904 expansion by the Junge family to increase their capacity and to capitalize on their success. While not every building legacy of the Junge Baking Company remains, the Cracker Factory survives as the current home of the Sebastian Equipment Company at 18th and Main Street.

The Architectural Legacy of Garstang & Rea: Junge Baking Company Cracker Factory

Posted in Buildings of Joplin, Joplin industry

Twisters, Cyclones, and Tornadoes of Joplin’s Past: Part I

The tornado of May 22 was the worst to strike Joplin, but it was not the first.

In May, 1883, a tornado swept through Joplin and the news accounts of the event appear to echo recent events. Just this past week, a story about Laverne the cat, who was rescued after being trapped in the rubble after sixteen days aired on local news stations. In 1883, Charley Elliott’s dog was “in his store building when it fell. He was dug out next morning pretty badly bruised, but after a few hours he was alright. There were acts of generosity. E.R. Moffett, who would later die impoverished, walked up to an “old friend who he had worked with before he became a millionaire. ‘Crit, I’m damned sorry, I’m sorry $500,” and then gave a five hundred dollar check to the relief fund. Citizens scrambled to help each other. Judge Byers was “constantly busy distributing supplies to the needy who lost their all by the wild winds.” Doctors Fannie Williams and Mrs. Creech did “good work for the suffering ladies who were injured” during the storm. Miss Fannie Hall of Carthage gave her all to assist the suffering at the hospital. Oronogo, also hard hit by the storm, was the focus of a relief committee made up of some of Joplin’s leading socialites: Mrs. L.P. Cunningham, Mrs. J.B. Sergeant, Mrs. J.C. Gaston, and Mrs. Thomas Heathwood. Together these women sought to collect food, clothing, and bedding for those effected by the storm.

For others, the tornado brought excitement and curiosity. The Daily Herald remarked, “Some of the visitors Monday night seemed to regard the occasion in the light of a picnic. Frivolities and flirtations were engaged in that would have been regarded impudent at a circus. No apparent sympathy was exhibited for the crippled, bereaved, and homeless, while silly children took the place of sober sense.” Sightseers came to stare at a “bushel basket that lodged in the top of a large tree near the railroad track.” Telegraph poles at the train depot reportedly looked like “they had passed through a storm of musketry.”

And then there were those that lost their lives. Preliminary reports reported that the bodies of a Mr. Goodwin and his daughter were killed by the tornado. It is unknown how many others lost their lives.

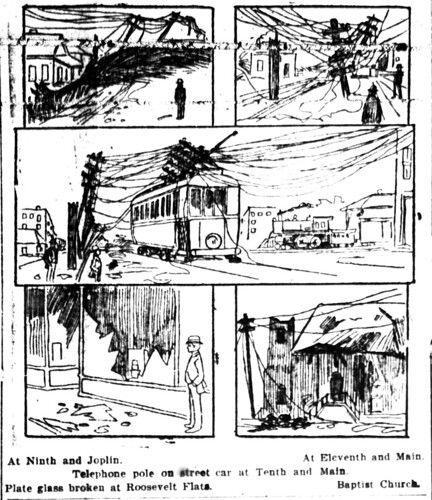

The next significant tornado to hit Joplin was in April, 1902. The News-Herald proclaimed it was, “[The] Worst That Joplin Has Known.” A wind, hail, and rain storm converged upon Joplin around 4:25 p.m. in the afternoon in an area described as covering “Seventh Street on the north and as far as Seventeenth Street on the south” with the worst areas at Moffett and Bird streets from Thirteenth to Sixteenth streets and at Moonshine Hill. Property along Main and Ninth streets received substantial damage.

The News-Herald reporter must have not known about the Tornado of 1883 as they declared, “As Joplin has never experienced a real tornado, the people were unprepared and as it came upon them so unexpectedly, it as a wonder that more fatalities are not recorded.” Telephone and trolley poles were twisted beyond recognition making communication with neighboring communities impossible. Streetcars were unable to run due to the lack of electricity and piles of debris covering the tracks. One car caught at Twelfth and Main, Car Number 41, was struck by a telephone pole. Passengers inside were “thoroughly frightened and several actually said their prayers.” Strong wind was not the only threat to human lives. The pole was described as having fifteen double cross arms with three large cables and several hundred telephone wires. Workers roped off the street to prevent traffic and pedestrians from going near the car. Passengers shakily disembarked and walked home on foot.

A “solid sheet of water, besides some hail” fell, causing people to hide inside their homes. Willow Branch, the Tenth Street branch, and other small streams in and around Joplin began to flood, leaving many to seek dry ground as the streams became “turbulent torrent[s] of water, mud, and wreckage.”

The storm indiscriminately took human lives and property. It was reported that the two room house of William Hunter, who lived on the east side of Moonshine Hill, was carried for a long distance before it shattered. Mrs. Hunter, holding her baby Esther in her arms, was about to flee the house when the storm hit. A plank of wood flew past and hit her child in the head, mortally wounding it, while Mrs. Hunter sustained serious injuries. Her husband, a miner, was at work at the Dividend Mine when the storm rolled through Joplin. A neighbor, Charley Whitehead, came to Mrs. Hunter’s rescue. Other residents of Moonshine Hill suffered the same fate. Will Douglass’ home was obliterated. Lee Whitehead [perhaps related to Charley] and family also lost their home. The Methodist church on Moonshine Hill was a complete loss.

Arthur Cox, owner of Cox Baseball Park, was one of the “heaviest losers.” The storm destroyed the baseball park’s fence, the grand stand’s roof ripped off, and sustained overall heavy damage. The losses were estimated at $1,000. Cox, however, was not one to stand idly by. Within a day, W.J. Wagy was hired to rebuild the park in time for a game just a day after the tornado struck.

At the corner of West Ninth and Tenth streets, several homes were damaged, if not utterly ruined. An African-American family named Smith lost their house and P.B. Moser’s home was demolished. A.J. Stockton was fortunate — he only lost his kitchen.

For the impoverished residents who lived in “shanties” north of the Missouri Pacific roundhouse between Grand Avenue and the Frisco and Kansas City Southern tracks, their impermanent residences were blown away.

White and black churches were not left untouched. The First Baptist Church was “badly wrecked.” The Methodist Episcopal Church’s South Mission location at Tenth and Grand was “completely wiped away.” The African Methodist Episcopal Church on East Seventh street was also destroyed. Despite being a substantial frame structure, the roof was torn off and the walls subsequently caved in.

The nuns at St. John’s Hospital were “buffeted and blown about by the wind as they strove in vain to keep out the sheets of water thrown against the west end south of the building which stands high and unprotected.”

Property damage was estimated at $50,000 and an estimated fifty to sixty houses destroyed. As soon as the storm passed, “ambulances and relief crews found work to do for many hours.” Mayor John C. Trigg released a proclamation that read:

“To the Citizens of Joplin — Authentic information having been received that the cyclone which visited the city of Joplin on yesterday, caused incalculable damage to many of our citizens and has been especially destructive to the poorer classes of our citizens in many instances to the extent of destroying everything they owned, leaving them destitute, houseless and homeless.

Therefore, for the purpose of alleviating the distress which prevails in the city and vicinity and to devise ways and means by the organization of relief corps, or by such practicable methods as may be suggested and agreed upon at a meeting of the citizens is hereby called to be held at the Commercial Club rooms, on the 25 inst., at the hour of 3 o’clock p.m. to consider the premises and take such appropriate action as may be deemed necessary therein.”

Joplin has always taken care of its own in times of need. When the committee met, it was agreed that many of those effected by the storm were impoverished miners who were in badly need of assistance, and a relief fund was created. Thomas W. Cunningham reported that when he checked on his rental properties in the damaged section of town he found that one of the families renting from him had been forced to cut their way out of the house. He decided that they “deserved the house” and “made them a deed for it.” His act of kindness was heartily applauded. It was thought that the family was that of I.W. Reynolds who lived at Thirteenth and Ivy. Mr. Wolfarth of Junge Baking Company pledged free bread to those in need. Arthur Cox and Don Stuart pledged the proceeds of the next baseball game to the relief fund. The Wilbur-Kirwin Opera Company decided to give a benefit performance for Joplin’s tornado victims.

Joplin rebuilt only to face another tornado six years later in 1908. That story and more in our next installment.

[Conclusion of Part I]

Posted in baseball in Joplin, Buildings of Joplin, City Government of Joplin, Events in Joplin, People of Joplin, Places in Joplin, Social Organizations of Joplin