CHAPTERS ERASED FROM JOPLIN’S ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY

By Leslie Simpson

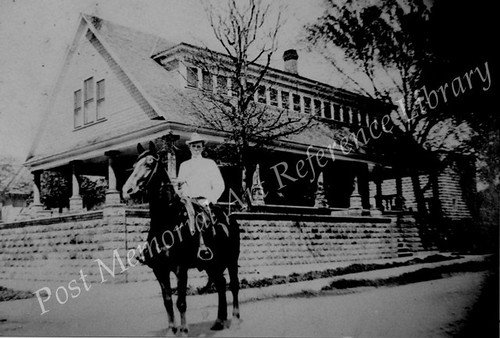

caption for photo: Carl Owen house at 2431 Porter. Built ca. 1911. Destroyed by tornado May 22, 2011 via Post Memorial Art Reference Library

I am having a difficult time knowing what to say. In fact, I hesitate to even write anything about brick and mortar, when human life, hopes, and dreams are what really matter. However, since I have written so much about Joplin’s architecture through the years, I feel compelled to say something. I have had several CNN reporters contact me for interviews, but I have not wanted to talk to them. First of all, I had not personally seen all the damage. It is impossible to get around, and I did not want to get in the way of emergency workers nor be a voyeur. Secondly, I just did not think I could articulate what has happened to my beloved Joplin. So now I will attempt some general (and unofficial) impressions of Joplin’s historic identity and how this incomprehensible tragedy has affected it. Also, rather than catalog specific buildings that have been lost, I will focus on three historic residential areas.

I begin with the historic town of Blendville in southwest Joplin, which was established in 1876 as “Cox Diggings.” The prosperous little community incorporated as Blendville, so-named because of the huge amounts of zinc blende in the ground. Thomas Cunningham owned the residential area, which he divided into lots and sold at low rates so that miners could afford their own homes. The city of Joplin extended its streetcar line to Blendville, with lines going south on Main to 19th Street, west to Byers, south to 21st Street, west to Murphy, then south to 26th. In 1892, Joplin annexed the village. Thomas Cunningham donated “Cunningham Grove” as Joplin’s first city park. The tornado took out most of the original Blendville area, including Cunningham Park and the historic water plant with some of the original equipment preserved inside.

The next area of historic significance is “Schifferdecker’s First Addition”, a residential area developed in south Joplin beginning in 1900. The Joplin Globe referred to the area lying south of 20th Street and fronting on Wall, Joplin, and Main Street as “a beautiful new addition affording the most desirable building property” to be found anywhere in the city. A second addition continued development south of 20th on Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania Avenues as well as along 21st, 22nd, and 23rd Streets to the east and west. The residential district continued to expand to the south throughout the teens, twenties, thirties. The homes in the region ranged from high Victorian styles to bungalows and eclectic Tudors, Colonial Revivals, Spanish mission, etc. Tragically, this charming old neighborhood has been wiped out.

After World War II ended, Joplin families faced a housing shortage. Some Camp Crowder buildings were moved to Joplin, while others were dismantled to provide construction materials. Hundreds of small efficiency houses were mass-produced for veterans and financed through FHA. Many of these were built in the Eastmoreland area. As people prospered in the 1960s and 1970s, they built more substantial brick homes east and south of the new high school at 20th and Indiana. Although most people do not think of these homes as historic, they do have their own place in Joplin’s architectural history, and their loss is devastating as well.

Entire chapters of Joplin’s history have been forever erased. I have not even touched on the loss of churches, schools, medical buildings, and businesses. Again, I am not relating the loss of our buildings to the loss of our people. Joplin will rebuild. It has already begun. During the first week after the tornado, I saw a business being rebuilt in the midst of the war zone surrounding West 26th Street!

Leslie Simpson, an expert on Joplin history and architecture, is the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, located within the Joplin Public Library. She is the author of From Lincoln Logs to Lego Blocks: How Joplin Was Built, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture. and the soon to be released, Joplin: A Postcard History.