Catch up on the history of the Joplin Depot’s origins with part one here and part two here.

The first view of the Union Depot which greeted the readers of the Joplin News Herald on March 1st

After the exciting publication of an architect’s drawing of the Union Depot on the first day of March, 1910, a debate may have erupted over the validity of the print. The News Heraldon the 28th of March, in one of the first updates on the depot since the beginning of the month, confirmed the accuracy with the arrival of the official plans and specifications to the city engineer’s office. The city engineer, J.B. Hodgdon, passed on the plans to several local contractor firms. It was the hope that a local firm would offer a satisfactory bid, such as Dieter and Wenzel, located in nearby Carthage and a company responsible for raising many of Joplin’s most well known buildings. Notably, the city planned to divide the construction process between building the depot structure and grading the land about the building. The land in question, the Kansas City Bottoms, located between Main Street and the Kansas City Southern tracks and between Joplin Creek and Broadway, was to be leveled.

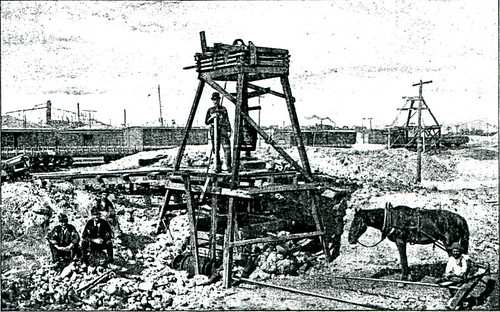

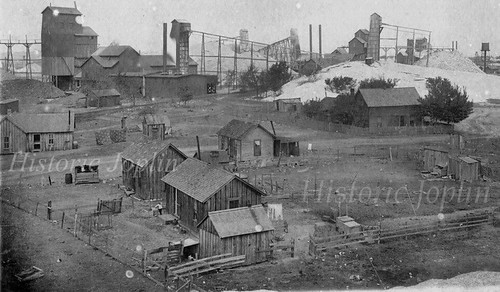

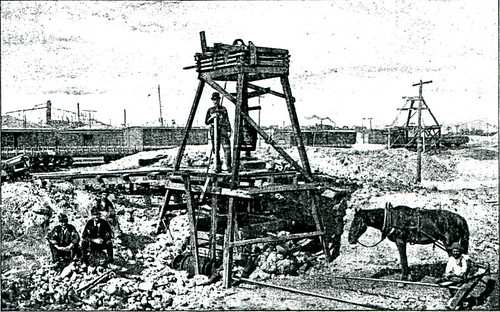

Two days later, the papers announced the appointment of E.F. Cameron as the local attorney for the Joplin Union Depot. The announcement was accompanied by a firm statement that construction would start April 1. In the meanwhile, the parties behind the depot had finalized the acquisition of properties within the desired realm of the depot and exploratory drilling had been done to ensure that no abandoned mines or “drifts” threatened to destabilize the foundation of the future depot. Indeed, the drilling had discovered solid limestone on average fifteen to twenty feet below the surface, and in some cases, even closer. Already, some of the uneven parts of the Kansas City Bottoms had been filled by the railroads to allow future track to be on level with existing rails.

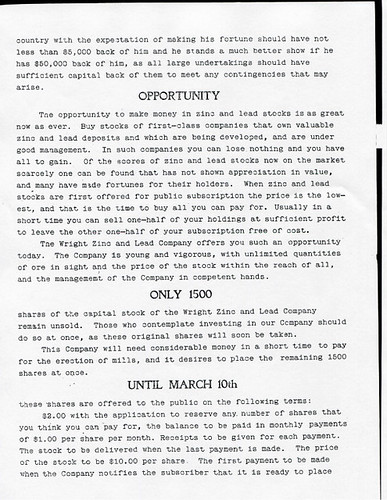

The site of the depot had once been the center of many mining attempts like the one above in the early days of Joplin, leaving many abandoned mines behind.

Six bids were submitted for the excavation, which required the removal of approximately 40,000 yards of dirt, and the Joplin firm Jennings & Jenkins was awarded the contract. “I will begin work,” declared W. F. Jenkins on Saturday, April 2, 1910, “with a full crew on the excavation on Monday.” Nine bids, two from Joplin area firms, were submitted for the construction of the depot structure. However, the selection of the firm was considered more important than excavation, and demanded a meeting of the chief engineers of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas, the Santa Fe, and the Missouri and Northern Arkansas, railroads. The architect, Louis Curtiss, available at the time of the bid announcement, promised that Joplin’s depot would be the most beautiful in construction, the most complete and convenient of any depot of the size in the United States. Indeed, Curtis noted, specifications called for “handsome interior furnishings and the most substantial exterior known.”

On the following Monday morning, a small force of men with three to four teams of horses arrived and began the work of excavation. The number of overall men expected to work varied from as little as fifty to four times that number, with as many four times the starting number of teams of horses. Afterward, it was reported that before rain brought an end to the day’s labor that fifty men with fifteen teams had been brought to bear against the earth.

The delay in selecting a contractor to build the depot structure was not critical, as all reports stated that such construction could not begin until the grading was complete. It was to be no small feat of work transforming the hilly area that offered a home to Joplin Creek into a suitable home for the new Joplin Depot. In contrast to the 40,000 yards of dirt discussed earlier, Jennings & Jenkins instead claimed they only had to remove 30,000 yards of soil. However, 135,000 yards of soil was required as fill, the present earth apparently being inappropriate for the task, and all of it to be hauled in by train.

The News Heraldsummarized the task ahead, “The hill along Broadway and Main street will be cut down and the dirt moved back onto the lower grounds. These hills will be cut down to a level of the grades of the streets and the fill along the Kansas City Southern railroad will be made on level with the tracks…The hill north of the Old Joplin creek bed will also be cut down and the dirt hauled into the low places.” Hills were not the only landmarks that needed cutting down, the paper referred almost in afterthought to, “Several buildings will have to be removed from the grounds during the next few days and a force of men will be set to work tearing them away and burning the rubbish.” The several buildings were actually homes to “persons who have occupied houses on the site for many years who repeatedly within the past month have been ordered to move.” No tolerance was given as the homes were to be destroyed as the excavation work approached them, not even “if the occupants have not sought other quarters.” The transformation of the Kansas City Bottoms was expected to take approximately two months.

Little of the old Kansas City Bottoms remains as it once was before the depot.

Only a few days after the start of the work, the excavators made a gruesome discovery three feet into the soil of the hill located along Broadway. The Daily Globe reported, “The bones found are crumbled with age, and, although apparently whole when unearthed, fall to pieces when picked up; Their sizes are thought too large for small animals and too small for horses or cows, or other of the larger domestic beasts.” Work came to a temporary stop as local residents were quizzed for knowledge of any remembered burials or graveyards. None were recalled. One such resident, who claimed to have prospected “all over the Kansas City Bottoms when a young man” had never heard of any burials.

The old prospector reminisced, “They might have been buried all right,” said he, “but it was not with the knowledge of the authorities or a permit from the coroner. There was a killing down here almost every day in them times, and I suppose they had to bury the victims some way.” The reporter of the Daily Globe noted that the majority of murders in the Bottoms were likely never reported, and the speculation that the excavators had discovered one unfortunate victim was very likely, an opinion shared by the Joplin police called to the scene. However, the contractors “scoffed” at the idea, most likely out of fear of losing workers who, “showed unmistakable signs of nervousness when the discovery was made…Several declared they would not work if they were convinced they were digging up bones of human beings.” Human remains or not, the excavation continued.

Another problem arose at approximately the same time as the excavators made their unpleasant discovery. Nine bids had been submitted for the contract to build the depot structure and to the consternation of the railroads involved, all were considered too high. The possibility of revising Curtiss’ design for the depot and re-opening the bidding process was proposed on April 8th. Five days later, the decision was made to do so and bidding was opened again until the 18th. The new bids were based on changes to the original design, contractor Fred Dieter reported, changes that “will not in any way effect the exterior nor the general plans for the building,” but rather consisted of, “a few substitutions in material.”

By the time the bidding process was closed, only six bids had been made, down three from the previous nine. A. F. Rust, the chief engineer for the Kansas City Southern, promised that the new bids all appeared to be a much more satisfactory in estimated costs. A week, the chief engineer promised, was as long as it would take for the winning bid to be selected. Nearly two weeks later, on April 30th, an authoritative source promised that the winning bid would be announced in two days, in part to coincide with a meeting of the chief engineers of the four railroads which backed the union depot company. By May 12th, James Edson, the president of the Kansas City Southern on a long distance telephone interview with a News Herald reporter, had to dismiss rumors that the depot was to be relocated to a 15th Street location. In the same call, Edson declared that a meeting of the board of directors of the Joplin Depot Company in the later half of May would choose the winning contract. Meanwhile, excavation continued with dynamite used to reduce a steep hill east of Main Street.

Finally, on June 5, a Sunday morning, it was announced that the Manhattan Construction Company of New York, with a branch office in Fort Smith, Arkansas, had been awarded the contract at an initial cost of $60,000. Construction would begin, stated a representative for the company, no later than June 15. The grading by the excavators was virtually completed, but the foundation of the building had not yet been begun. The two city papers offered slightly different reports on the design of the building, the Herald claimed, “The trimmings will probably be of Carthage stone, according to the original plans,” along with brick and concrete, and the Daily Globe in turn stated, “The contract calls for the erection of a modern building, of reinforced concrete construction.”

Six days later, Rust visited the site of the future depot and promised again that the depot would be completed by the end of the year. The chief engineer noted that already enough steel for four miles of track was at the site and that, “We intend to push operations as fast as possible,” and bragged, “only material of the highest grade will be put in the depot. The station will be built with a view of accommodating Joplin when it is considerable larger than it is now. In my opinion, and according to officers of the depot company, Joplin is one of the coming cities of the Southwest.”

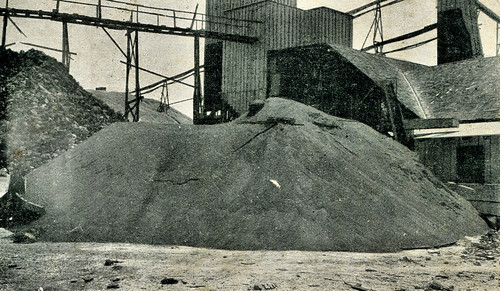

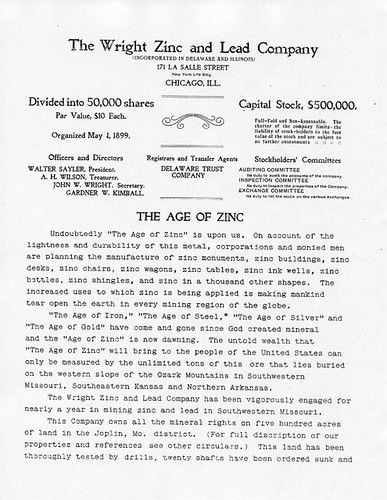

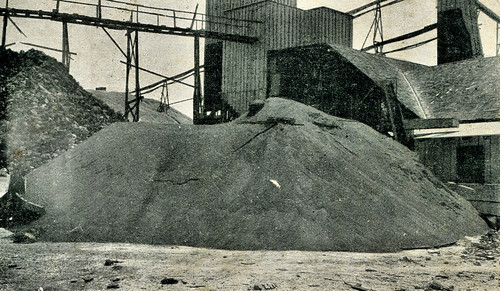

By mid June, excavation work uncovered yet another discovery, zinc. Within a week of the find, nearly a ton of the ore had been sold at a price of $23 a ton. While the contractors considered applying the new found source of wealth toward the cost of construction, two men from the excavation crew were assigned to sort the soil. The quality of the ore was shortly considered rich enough that some of the men involved in its examination immediately organized a mining company, procured a lease to do the mining, and set upon the deposit. The vein was found to be only a few feet beneath the soil, at least seven feet in depth, and in lieu of building a processing plant, the miners hauled away the dirt in wagons to nearby plants for processing to separate the zinc from the soil, as well any lead. By August 4, the entrepreneurs had sold nearly $1,900 worth of lead and zinc, and were still at work at their enterprise.

A pile of processed "Jack" valued at $100,000.

The excavated area, located “near the heart of the old shallow diggings on Joplin creek” had once been the home of St. James hotel and also the “crimson lighted district.” Old settlers, ever present to discuss such events, recalled the days when “the valley sloping off to the northeast resembled a bee hive. Mines and miners were constantly working there. Before many years had elapsed the ground looked like an overgrown pepper box.” However, due to the presence of the hotel and other sordid activities, few thought to mine the area, or so the theory went. The News Herald quipped, “If the owners of the new property do not see fit to construct their new depot they can mine.”

“Grading of site is nearly completed,” announced the Daily Globe, on June 16. By the efforts of the excavators, the paper reported that “the hills to the north have been leveled, while many of the lower points have been filled and the surface rolled.” Though, it took another four weeks to complete, the impact on the local geography was significant. In addition to the annihilation of hills, the “surface of the ground has been lowered seven feet…in the higher places, and from that to two feet in the lowest parts.” For the low parts of the depot area, fill was used to raise the surface from two to four feet. Extreme summer heat, contractors claimed, was the culprit for the long delay in the completion of the excavation. The teams of excavators gone, the site absent of working men and horses, for a brief time was considered to possess an “absolute quiet.”

A visit to the site at the time would have revealed a number of temporary buildings built to house the materials needed to construct the depot. The gathering of which had been ongoing for weeks. Another significant addition, and alteration to the geography, was the culvert built to guide the waters of the Joplin creek under the Depot site. When completed, the culvert was expected to be 631 feet long and possess a 6 foot radius. Through it the creek named for the Methodist preacher, Harris Joplin, would eventually disappear from sight for a stretch of more than two football fields. Nor was it the only effort to divert water, as a “great double aqueduct” was also being put into place to convey a stream from Main Street , built of concrete, it was two tubes each four feet in diameter and two hundred yards long. When done, it was believed the aqueducts would be able to “convey a larger amount of water than has ever been seen in the little branch.” The exit point for the aqueducts was in the area of the Kansas City southern bridge.

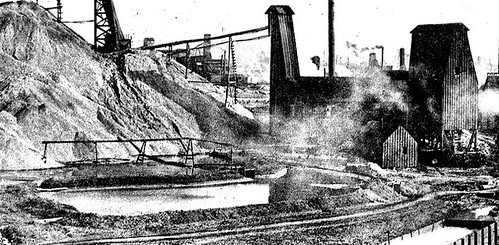

Off the site, at approximately the same time as excavation work was concluding, the Kansas City Southern filed a mortgage for the value of $500,000. The mortgage was intended to secure the $500,000 in bonds that had previously been sold by the depot company to finance construction. Nor was the Kansas City Southern the only railroad company involved with large sums of money. The Missouri, Kansas & Texas, or Katy, Railroad was busy with the construction of a spur from its main line to reach the Depot at a cost of around $250,000. Much of the cost had to do with traversing hollows and areas dotted with old mines and sludge ponds, which demanded the construction of bridges or the use of fill to stabilize the ground. One such required bridge was to be located over Possum Hollow and would be a “22-panel pile trestle bridge” that would carry trains 47 feet above the floor of the ravine, and 30 feet above an existing bridge built by the Frisco Railroad. Along with its own expense in the cost of terminals at the depot, it was estimated the Katy would ultimately spend $500,000.

While the Katy Railroad continued its investment into the depot, another railroad decided to investigate the possibility of joining the enterprise, the Frisco Railroad. As covered earlier, the Frisco Railroad, through its interests in Joplin, had furiously attempted to stop passage of the union depot franchise by the city’s council. However, almost two years had passed since its failed attempt and faced with a desire to expand its freight capabilities by the cheapest means necessary, the Frisco opted to further investigate the matter. While the Frisco had a depot in Joplin, it believed that if it could direct its passenger traffic to the union depot, it could then enlarge its freight capabilities at the existing depot. Despite reportedly being on of the largest landowners in the city of Joplin, the Frisco was having trouble parting Ralph Muir from the property he owned at the corner of 6th and Main Street, which it felt was needed were it to expand its passenger area. The vice-president of the railroad, Carl Gray, promised a decision would be had in a couple weeks. Ultimately, however, the Frisco did end up building a new depot, after it did finally acquired the coveted 6th Street and Main property.

The depot the Frisco later went on to built, still standing on Main Street Joplin today.

Meanwhile, as work concluded on the main excavation, on July 24, 1910, the Joplin Daily Globe, noted in a small article, far from the headlines of the front page, that the Manhattan Construction Company “Will Start Erection of Depot Tomorrow.” Representatives of the company were to arrive on the 25th, along with a foreman, who’s task was to oversee approximately 25 men and the start of the foundation, which included the further excavation of fifty square feet for the new home of the depot’s heating apparatus. The depot itself was finally under construction.