Many months back, we created video slideshows from old photography books of Joplin and posted them on Youtube. Now they are accessible on our site without hunting them down elsewhere. Just click on the “Video” tab at the top of the site on the right. Enjoy!

Reckless Wheelmen of Joplin

In 1897, the Joplin Globe reported that a large number of cyclists were ignoring a city ordinance that required cyclists riding at night to use a headlight. The paper called upon the Joplin Police Department to enforce the ordinance after a large number of complaints had been made by “persons who have narrowly escaped being run down at dark corners by reckless riders.” While no accidents had taken place, “several new profane expletives have been added to the vocabulary by people who have been made to jump sideways or straight up in order to avoid being run over.”

The Globe wryly suggested that the irresponsible night riders “lose a few spokes out of a wheel” and fly through the air as it would do them more good than a “little fine.” The ordinance should be enforced, the Globe demanded, instead of people carrying shepherd’s crooks at night to fend off “bicyles ‘running wild.”

Curiously during this era, Joplin, Columbia, and Carthage all passed city ordinances that would have prohibited the use of bicycles within each city. The Missouri Division of the League of American Wheelmen went to court and defeated each ordinance, leaving Joplin residents to dodge and fend off careless cyclists.

Source: Joplin Daily Globe

A story from an earlier Joplinite

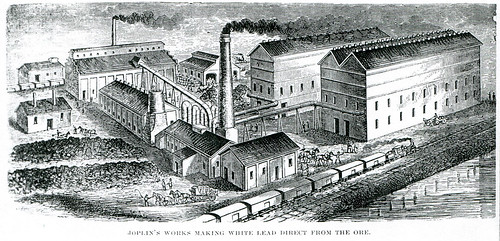

W.S. Gray, a machinery dealer located at 718 Jackson Avenue in Joplin, regaled a News-Herald reporter with stories of working for Moffet and Sergeant in the early 1870s.

Gray told the reporter, “I saw an article about the Cave Creek, Ark., zinc district in your Sunday issue,” he said. “it reminds me of the good days; it reminded me of the longest hike I ever undertook — a nice little 300-mile jaunt, all the way from Cave back to Joplin; and say, my friend, I always liked fish, but let me tell you I ate so many fish on that hike that I couldn’t even look a bottle of fish scale glue in the face for two years; and I snubbed one of my best old friends, John Finn, because the son of his name made me sick — but I’ve since recovered and can eat as many fish today as ever.”

He continued, “I was in the employ of the Moffet and Sergeant smelter here when I received an offer to be superintendent of construction at an air furnace that was to be built in the Cave Creek, Ark., district. It was my first job as supe and I was so proud of it. I broke the sweat band in my hat. It was about ’76 when we lined up for duty in the Arkansas wilds and began work on the new smeltery. Some time later things were running fine and we shipped a couple of carloads of lead — the pigs being carried overland in wagons to Russellville, Ark. When we came back to work again at the furnace the head bookkeeper drove over to a little place to get some drafts cashed. He sold the team and never came back — and not a cent of money did I get for my first job as superintendent. So the smelter closed down, and Lem Cassidy and myself — Cassidy is long since dead — started back afoot for Joplin. We knew the houses would be few and far between and that our grub must largely consist of fish. We laid in enough tackle to carry us through and started. Grasshoppers made the best bait imaginable and we had no trouble keeping our larder well stocked. We carried a little skillet, a coffee pot, and blankets with us. It was in the fall of the year, and walking was delightful. I have aways looked upon this jaunt as one long vacation. We took our time and enjoyed the beauties of the country. Sometimes we were fortunate in getting bread and vegetables from farmers, but such occasions were rare.”

According to the annual Report of the Geological Survey of Arkansas for 1905, lead mining began in the Cave Creek, Arkansas, mining district in 1876. “The pig lead was hauled by wagon to Russellville on the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railway and thence shipped to Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.”

Source: Joplin News-Herald

Big Trouble in Little Joplin

Despite the widespread fear of the “Yellow Peril,” not all Americans viewed their Chinese neighbors as economic competitors or sinister agents of the Chinese Emperor. It also helped if they were hard working Christians. Preston McGoodwin, a reporter for the Joplin Globe who went on to serve as U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela, profiled one of Joplin’s Chinese residents, Ah King.

King, owner of the Crystal Laundry located at 818 South Main Street, was lauded by McGoodwin as a “devout Christian worker.” He arrived in San Francisco, California, at the age of fourteen sometime around 1880. Although he did not tell McGoodwin how he ended up in the Midwest, he did relate that he arrived in Joplin in 1900 after living in nearby Springfield, Missouri. He reportedly astounded members of Joplin’s small Chinese community when he announced he was a devout Baptist. McGoodwin informed the Globe‘s readers that King “differs materially from the average church and association members in that he is at all times devout and intensely sincere.” McGoodwin also praised King for his “scrupulously clean” business that employed several white girls who washed and ironed customer’s clothes. King’s luck did not last.

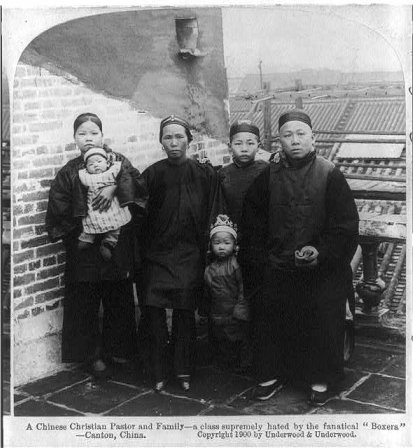

A few months later, the Joplin Globe reported that Ah King and his brother Sam Long left town after he fell behind on rent to the Leonard Mercantile and Realty Company. It was noted that King had always borne an “excellent reputation” and was a “consistent member of the Baptist Church.” Joplin residents who knew King insisted he left to find money to pay his landlord, he left behind in his wake two angry female employees who were forced to wash and iron laundry to make up for their lost wages. “He owes us, the wretch,” one of the girls growled as she starched shirts. Her compatriot added, “It’s a perfect outrage to treat us girls so.” Others thought that King was spirited away by members of the Boxers, an anti-Western Chinese group, because he openly expressed his disapproval of the group. King did not return to Joplin.

Chinese Christians, as pictured here, were detested by the Chinese Boxer Movement. This may have been why some believed the Boxers to be involved with King's disappearance.

Another one of the handful of Chinese residents in Joplin, Jung Sing, also experienced misfortune. Sing, who ran a “chop suey restaurant” on East Fifth Street, was arrested for selling opium. After he bonded out of jail, he returned home to find that his American wife had left him, taking his entire savings of $700. As Sing said (as crudely rendered by a Joplin Globe reporter), “She done skippee. When I fin’ she make getaway, I lookee in clash legister. All empty. Lookee in safe. Empty. I makee to fin’ out how much gone. Seven hundred dollar. I marry China gal next time.”

It was not the first time that Sing had had bad luck with women. After arriving in New York, he opened up a restaurant and married an American citizen. Together they lived in New York City’s Chinatown until one morning he woke up to find that she had disappeared. After searching their abode, he found she had taken $1000 of his money. Sing soon left for San Francisco where he met his second American wife. Together they moved to Joplin and lived there until she left with his money. When asked if he planned on catching her, Sing shook his head and said, “No, no. Makee no fuss. Never get seven hundred dollar back anyhow. Marry China gal next time.”

A chop suey restaurant in Chicago. Restaurants were always an option for immigrants seeking to find their place in a community, like Sing in Joplin.

Sing’s luck did not get any better. A few days later after his wife left him, two men came into his restaurant and refused to pay the bill. When Sing demanded they pay, the men attacked him. The proprietor ran to the back of his restaurant, grabbed a revolver, and chased the two men out onto the street. He fired two shots but failed to hit either man. After an investigation, Sing was arrested for disturbing the peace by Deputy Constable Norman Bricker. His fate is unknown, but one can hope that he found a wife who would not run off with his cash.

The experiences of Sing and King represent one more window into the world of Joplin’s Chinese immigrants. Did every immigrant come across similar bad luck or were our two migrants featured here the exception? Although historians cannot judge whether or not either man was truly accepted as a member of Joplin society, King may have been looked upon more favorably, as he was a devout Christian. Sing, on the other hand, may not have been as tolerated because he had been charged with selling opium and was married to a white woman during a time of great racial intolerance. Perhaps both men were fortunate enough to obtain their American dream far from the shores of the Celestial Kingdom.

Sources: Library of Congress, Joplin Globe.

The Chinese Immigrants of Joplin

Walter Williams, founder of the University of Missouri’s Journalism School, once wrote “Joplin is a city of self-made men, nearly every one of the moneyed citizens having made his fortune there. They are largely American born and American educated.” As Williams observed, Joplin was primarily populated by American citizens, but there were many immigrants who called Joplin home. Few, however, were Chinese.

Chinese immigrants arrived on America’s shores beginning in the late 1840s during the California Gold Rush. Two decades later, even larger numbers of Chinese laborers were recruited to work on the Transcontinental Railroad. The influx of cheap labor and threat of economic competition sparked racial animosity. Violent anti-Chinese riots broke out in several American cities, including Denver, Seattle, and Rock Springs, Wyoming. In 1882, in response to growing outrage over Chinese competition, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act suspended Chinese immigration to America for a period of ten years. Only those Chinese immigrants who arrived prior to the act’s passage were permitted to stay.

An illustration from "The Wasp" a magazine of San Francisco often noted for its virulent depictions of Chinese Immigrants. Available from the Library of Congress

At the turn of the century, both St. Louis and Kansas City were home to sizable Chinese communities but the Chinese presence in Joplin was less substantial. Historians can be stymied by gaps in the historical record. The earliest Joplin city directory to have survived the ravages of time dates to 1899, leaving a gap in the city’s history that ranges decades. Meanwhile, county histories often overlooked and ignored the presence and contributions of minorities. Although the state of Missouri attempted to collect birth and death records beginning in 1883, the effort failed until 1910, when the Missouri General Assembly passed a law making it mandatory for counties to record birth and death information. Few archival collections can boast of letters, diaries, and manuscripts from early Joplin, much less one kept by Chinese resident. Thus, it is often difficult to piece together the history of an immigrant group at the local level, especially if it was a particularly small immigrant group.

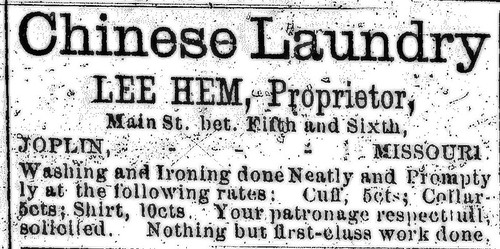

According to the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, there were no Chinese immigrants living in Joplin. By 1880, however, at least one Chinese immigrant called Joplin home. Lum Wong, a single twenty-seven year old native of China, listed his occupation as “servant — clerk in store.” He could not read or write English. Wong lived with sixty-four year old Jacob Wise, a retired merchant. A few years later, in1883, an advertisement appeared in the Joplin Daily Herald for a “Chinese Laundry” run by Lee Hem.

Although Lum Wong did not appear in the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, five other Chinese immigrants are listed as residents of Joplin. Most, if not all, worked in the laundry business. G. Goro, a thirty-six-year-old immigrant, lived on Main Street. According to the census, his neighbors described themselves gamblers, blacksmiths, day laborers, miners, and traveling salesmen. Sing See, Jung Jin, and Low Chung described themselves as “partners” in a laundry. See and Chung listed the year of their immigration as 1877 while Jin arrived in American in 1879. Thirty-four-year-old A. King, who roomed in a boarding house on Main Street, listed his occupation as “Chinese laundryman.” Unable to work in the mines, Chinese immigrants were forced to eke out their living in whatever industry was accessible, and often greatly restricted along racial lines.

Albert Cahn, a German-born clothing salesman who spoke at the opening of the Joplin Club in 1891 echoed the words of many American politicians when he declared, “This is the best apple country to be found and had Adam and Eve been placed here that Garden of Eden story would never have been told. We have vineyards here for the German, railroads for the sons of the Emerald Isle, commerce for the English, but no use for the Chinese.”

By 1910, only two Chinese immigrants lived in Joplin. One, Jung Low, gave his occupation as “Chinese laundry.” The other, John Jungyong, ran a restaurant.

Within ten years, the Chinese population in Joplin grew when Toy Jung, an immigrant to America since 1890, opened a Chinese restaurant. Toy, the proprietor, was assisted in his business by a partner, Ling Kwong, who had reached the states five years after Toy. Additionally, five cousins of Toy worked as cooks and waiters. Only two of Toy’s cousins were born in California; Toy, his partner, and his three other cousins were all born in Canton, China. Another Chinese run business listed in 1920 was a laundry run by a Chinese-American named Charlie Hoplong.

The 1930 Census revealed the presence of another Chinese restaurant run by Shang Hai Lo, a sixty-year old restaurateur from Canton, China who had arrived from China the same year as Toy Jung. It also noted the absence of Charlie Hoplong and his laundry business. Four years later, Toy Jung, who had spent at least fourteen years in Joplin, passed away leaving only his wife Quong Jung to mourn his death.

Today there are a small number of Chinese residents in Joplin. If you want to sample some of the finest Chinese in the Midwest, stop by Empress Lion. This small, unassuming restaurant located in a strip mall at the corner of 32nd Street and Connecticut, offers some of the finest Chinese to be had. (We hope you’re well, Tiger and Lily!)

Sources: United States Census, “History of Jasper County and Its People” by Joel Livingston, and the Joplin Daily Herald, “The State of Missouri” by Walter Williams, and the Library of Congress.