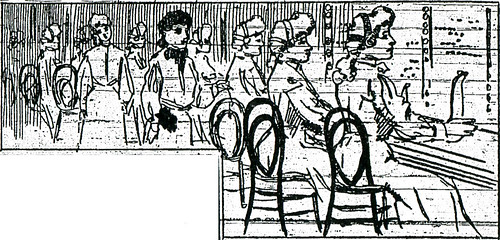

Hello Girls, which we have written about in previous posts, were known for their helpful and sunny disposition. Occasionally they found a reason to strike. In one instance that occurred in 1902, the sixteen day-shift Hello Girls employed at the central office of the Mineral Belt Telephone Company went on strike. Callers from 7:00 to 7:25 p.m. were undoubtedly confused when they picked up the phone and found that no operator could be reached.

Did they strike because of poor wages, low morale, or chauvinist bosses? No. They went on strike because the company hired one Winnie Arnold. Miss Arnold was a “blonde young lady from South Joplin. It was on her first night shift that her would-be colleagues decided, “her society was not acceptable to us, although she does work at night. We are endeavoring to keep within our ranks a class of workers, who are patient to all the whims of the patrons of the telephone.” After complaining about Miss Arnold to the company’s superintendent, he promised, “she could work no longer.” Presumably she was asked to leave the company’s employ and found work somewhere else.

While just a brief episode in Joplin’s history, the article provides some insight into the social class thinking of turn-of-the-century Joplin society. Young men and women who did not meet the societal standards of Victorian America could expect to be frowned upon by members of the middle and upper classes. The best society women did not work, but for those young women who did seek to earn a living, a desk job under the watchful eye of male managers provided a safe and morally clean environment. Those who could not meet the social and moral code of the day were not tolerated, lest their influence corrupt or taint their fellow young women.

With the coming of women’s suffrage, prohibition, World War I, and the swift pace of change during the 1920s, life changed dramatically in the next few decades for women. Such fears over the influence of individuals from one class or another, good or bad, waned. The result was a post-Victorian society that has evolved into the present day. Hopefully, the South Joplin girl was able to find a new job with better coworkers.