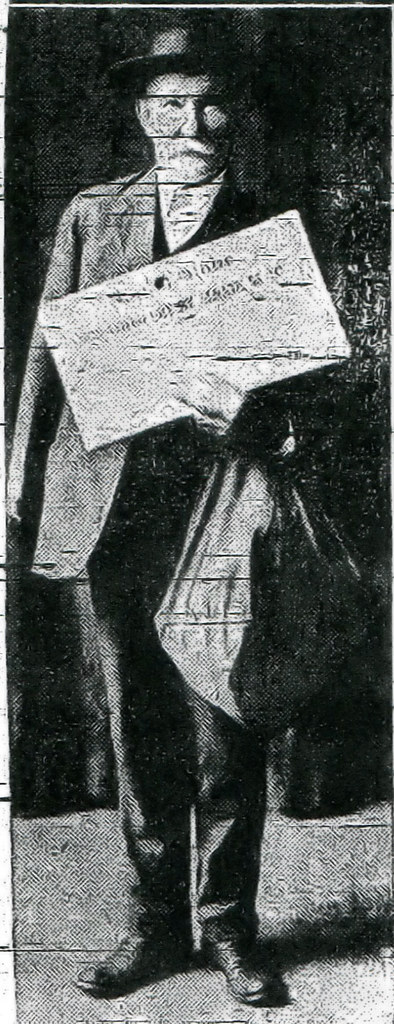

On a March day in 1919, a white-haired mustached old man strode into the offices of the Joplin Globe and inquired about a position as a newsboy. In addition to his age, the right sleeve of his jacket hung limp, his arm had been amputated many years ago. His name was John Connell and he got the job.

Life had not been kind to John Connell. The son of Irish immigrants, he fell from a tree and broke his arm when he was eight. His father, a wealthy man, hired a physician but money was not enough to save John’s arm. It became infected, the flesh of his arm died, and had to be amputated. When his parents passed away, Connell received an inheritance of $10,000. Flush with cash, he operated his own business and soon married. Life might have been a happy one, but it was not long after that his wife fell ill. Physicians said an operation would save her, but she died in a hospital after complications from surgery.

Widowed and with his business in shambles, he moved from Columbus, Ohio, to Cleveland, but fared no better there. His savings were soon depleted. John sought work but few businesses would hire a one-armed man. A position as a restaurant cashier was the best he could find, and such positions he held until he was hired by a Chicago portrait company to hit the road as a canvasser. And so, Fate, which had long been cruel to John Connell directed his path to Joplin. There, Connell realized he could make more money selling the Joplin Globe than as a canvasser, and convinced the newspaper to hire a one-armed 46 year old man to join the ranks of “newsies.”

Success came quickly. Not only did Connell excel at selling newspapers; he earned the admiration and love of his fellow newspaper boys. Such was his success in what he called “the game,” that Connell believed he could make even more money in a big city like San Francisco. Connell departed for bigger cities and hopefully bigger fortunes. In the larger cities and more competitive markets, he soon discovered that money was not as easily made and he bounced around the West and South, from places like Los Angeles, Denver, and New Orleans.

For thirteen years, Connell traveled the country, but never found a city like Joplin. He returned to the city and promptly applied for the position he had left so many years ago. Perhaps wary at first of the grandfatherly figure that joined their ranks, the newsboys soon extended affection to Connell. He became their mediator in disputes over who had a right to a certain “corner.” Connell also dispensed advice that only a fifty-nine year old man had to young boys who grew up on the streets hawking papers. Every night at 1 a.m., Connell awoke and collected the Globe’s 2 a.m. edition to sell to workers coming off the night shift, and then later sold a later edition at 11 am. The 1920 Federal Census found him a year older and his profession described as “newspaper distributor.” He may have been a 60 year old one-armed newspaper boy, but Connell earned the respect of the young men he worked with and upon him they bestowed the fond sobriquet, “Dad.”

Sources: The Joplin Globe, 1920 Federal Census