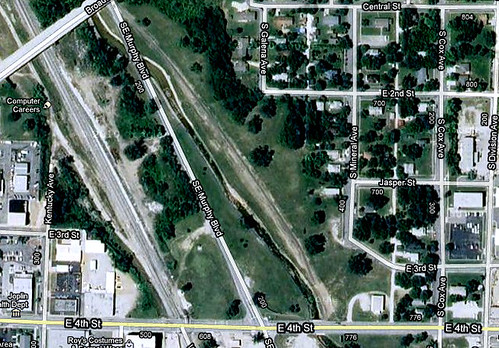

Its absence regularly goes without notice, and unless one is driving along Third street, crossing Main Street eastward, its former utility cannot even be contrived. It is now just a missing space on the map and a memory quickly fading as those who once recalled its presence disappear from the community. It served Joplin for approximately forty or more years, in one form or another. It connected the city’s two halves, East and West Joplin, and finally offered a means to ascend Broadway Hill, an “unpaved, rocky” road that was “a terror to teamsters and distinctly unpopular with all classes of travelers.” It was the Third Street Viaduct.

The union between Joplin in the East and Murphysburg in the West to form modern Joplin in the early 1870’s was at first more apparent in paper than in geography. A small valley and creek generally separated the two, the area once known as the Kansas City Bottoms, and now the home of the Union Depot and parkland. It was the site of Joplin’s first mining endeavors. Thus, the road that connected the two ran through mining camps, which a Joplin Daily Globe reporter referred to as a “tenderloin” and one that law abiding travelers hesitated to venture through on their way from one part of the city to the next.

While the Southwest Missouri Railroad connected the two parts of the town with streetcar service by 1906, there was still not a quick or convenient means to go from the heart of the Joplin business district to the east Joplin. The result, as the Globe put it, was that “Main Street merchants watching the expansion of the city in all directions saw that East Joplin, closer to the business center than South or West Joplin, was being overlooked by home builders because of the inconvenient route…” A solution to the problem had first been proposed about four yeas before 1906, in a conversation between T.C. Molloy, and the owner of the Globe, and at one point, also the House of Lords, Gilbert Barbee. The answer was a viaduct.

Little came of the discussion, other than the belief that Third Street should serve as the location of the viaduct, bridging across the bottoms to the hilly part of East Joplin. It was not until 1906 that the topic finally made ground and in December, 1907 the City Council passed an ordinance calling for a special election to approve the selling of $50,000 in bonds. Mayor Jesse Osborne quickly signed off on the ordinance and an election held on January 15, 1908, resulted in an overwhelming approval from the electorate, 1,366 for and just 274 against. A sell of bonds occurred in May, and resulted in just over $51,000.

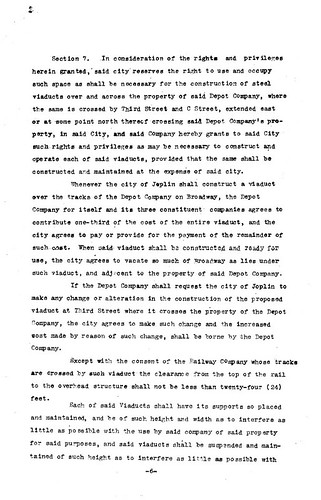

This page of the Scullin Franchise agreement required assistance in building the viaduct. Click on the image to be taken to a larger version.

Only a few months later, the construction of the viaduct was caught up in the debate concerning the granting of the Scullin franchise to establish and build a Union Depot in Joplin. It was not coincidence that Councilman Molloy took the forefront of the debate in the City Council meeting by vouching that as part of the deal, the Kansas City Southern Railroad would commit to paying approximately one-third of the Third Street viaduct. The Kansas City Southern was true to its word and the construction of the viaduct became part of the franchise that eventually was passed by the council and signed by Mayor Osborne on October 26, 1908.

In the end, the railroad ended up paying approximately $20,000 of the cost of the viaduct, and the Henry L. Doherty & Company successfully bid to construct the mostly steel bridge for $40,000. An additional $10,000 was also spent on building concrete pedestals, which required the use of a mining drill to ensure they were not placed over one of the many mine shafts which still honeycombed the area. The actual steel work of the bridge was crafted by the Southwestern Bridge Company, and sent in pieces from the plant and then sent to the site for assembly.

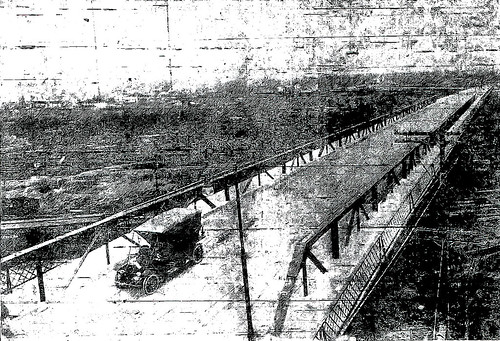

The actual construction was boastingly described, “The viaduct is said to be equal to any bridge of the kind in the United States from an engineering standpoint. It is of all steel construction with concrete flooring, covered by a three inch layer of creosoted wood blocks, laid paving fashion with asphalt filler.” The wood blocks were noted as a new innovation with “many advantages over brick of asphalt paving.” In fact, the blocks were “light, impervious to water, and are said to outwear bricks.” The floor of the bridge was concrete, reinforced with steel rods. Above this an actual paved street was laid out.

A colorized version of the newspaper photo from above allows for a better view of the viaduct's lamps. Via Missouri Digital Heritage

The viaduct was completed in the last week of September, all but the aforementioned paving, in 1909. It was one part of a signature moment for the city, which was flushed with a continual procession of beautiful buildings and other civic improvements being constructed. A period of growth yet unrivaled in the city’s history.

The viaduct was described as having “a six foot walk, raised eight inches above the level of the roadway and protected on the outer edge by a high latticed railing.” Light was provided by arc lights, each with the power of 2,000 candles. Powerful enough to not just illuminate the viaduct, but also designed to illuminate the dark area of the bottom land below.

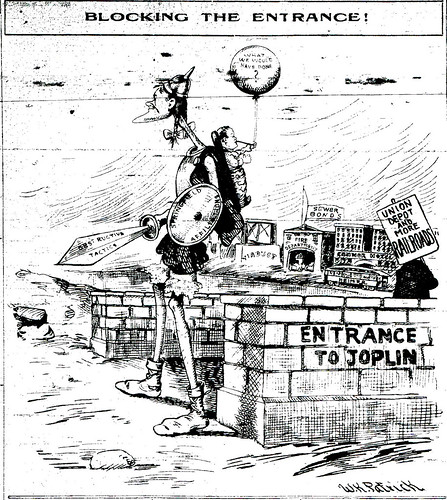

As this political cartoon illustrates, the viaduct was considered an achievement on the same scale as the Connor Hotel and the modern fire department.

The impact of the bridge was immediate. It was claimed that real estate values in East Joplin shot up anywhere from 100 to 300%, with new homes being constructed in the area. On the other side of the viaduct, new buildings were quickly being erected north of the busy business district of Fourth and Main streets. For the next several decades, the viaduct served as a landmark of Joplin, the conduit which connected the two parts of town and helped forged them into one.

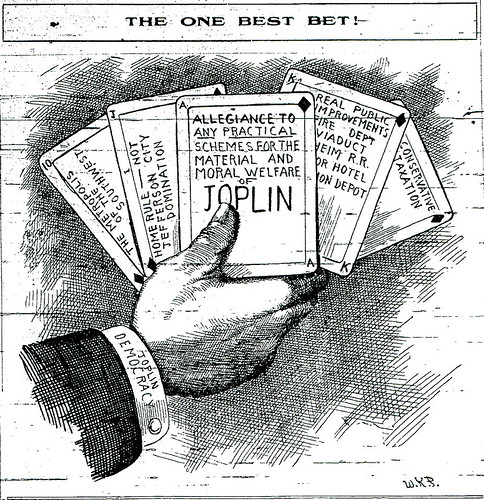

In another political cartoon, again the viaduct is in good company, as seen on the playing card above.

In what was at least one death connected to the bridge, Joplin Detective William Woolsey, was gunned down upon the span on December 8, 1917 in an attempted robbery. The officer had been crossing the viaduct with another when Frank Warren and Chub Hardin came upon the two. Warren shoved a gun into the detective’s stomach, but it was not enough to dissuade the Joplin police officer from pulling his own. In a tragic case of misfire, Woolsey got the drop on Warren and pulled the trigger with no result. By the time the shock wore off on both men, each tried to fire, Woolsey for the second time. This time Woolsey’s pistol worked, but so did Warren’s. The result was both men felled by fatal gunshot wounds to the abdomen.

The city sought to protect the community at large in 1924 by placing a load limit of 7,000 pounds on the viaduct. Likewise, it directed the Joplin Police to divert traffic from the bridge at the busiest times of day. As the years passed, the condition of the viaduct worsened. In 1943, the City Council made the fateful decision to close the bridge to all but pedestrian traffic out of fear of its “dangerous condition.” Two years later, as the Second World War was in its fourth year, the city was only able to make temporary repairs to the viaduct with the construction of a support column (to replace one which had broken). Due to the global conflict, materials and money were scarce, and it was hoped that much needed permanent repairs would happen after the war.

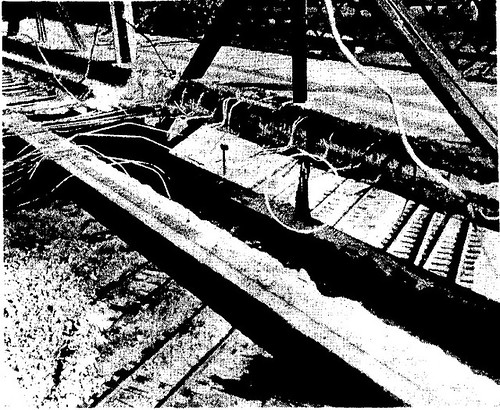

A disturbing example of the rust afflicting the viaduct, note the circled steel beam was once the same width as the beam above it.

The permanent repairs never arrived. By 1955, the viaduct had been effectively abandoned by the city for a decade. In February, the City Council made the decision to have the viaduct removed. Concerns existed, as the bridge continued to deteriorate, that pieces of falling concrete would strike pedestrians or vehicles below in Landreth Park or on Murphy Boulevard. The Council handed the task to the City Attorney, Loyd Roberts, while City Manager, J.D. Baughman could offer no expected cost of removal. One councilman, W. H. Clark, suggested that perhaps the Kansas City Southern might be induced to pay for some, if not all the cost. The argument was that the sulphuric acid in the coal burning trains had helped to erode the steel.

Two months later, the City Council reaffirmed its decision in April. It was not received happily by all. A hastily organized East Joplin Civic League appeared before the Council and argued that the viaduct be repaired, not removed. Alarmed at the prospect of being cut off from the city’s downtown, the League was supported by a petition of 75 signatories, and the treasurer, A.F. Brooks spoke on its behalf before the council. While Brooks believed the cost to repair was approximately $79,000, the City Council countered that Sverdrup & Parcel, Inc., an engineering firm from St. Louis, had estimated the actual cost at $192,000. That sum, arrived upon in 1953, undoubtedly helped push the Council to its position of removal over repair. Furthermore, an investigation by Traffic Lieutenant Clifford Hill, supposed that a repair would not be worth it unless Third street was strengthened and extended to Rangeline. Despite the protests of the East Joplin Civic League, the city moved forward on the viaduct’s destruction.

A view of the viaduct as demolition proceeded. The removal of the road surface exposed the viaduct's skeleton.

June saw the City Council instruct the City Manager Baughman to seek bids from companies for the viaduct’s removal. The hope, for the city, was to spend as little as possible and even possibly make money from the salvage value of the bridge’s materials. The contract was finally awarded in July to the V.R. Freer Construction Company, which offered to demolish the viaduct and pay the city $1,200 to salvage the steel. It was noted at the time that the concrete would be reused for civic improvements elsewhere.

October saw the end of the viaduct. In its destruction, it provided over 1,000 tons of asphalt which at some point was likely applied to road building projects elsewhere by the city. At the time of demolition, it was argued that the steel of the bridge had been prematurely rusted by the train smoke, which created an odd contrast. The viaduct had been in part paid for by the railroads and by 1955, was being demolished because of it. A personal tragedy also accompanied the viaduct’s demise. Despite the deconstructed state of the viaduct, barricades at both ends, Joplin resident, Arthur Yates, decided to stroll across the viaduct only to fall through a hole and plummet 30 feet to the ground below. Luckily for Yates, he was not killed, but might have been paralyzed below the waist for life.

By 1956, the viaduct was gone. Third Street became something less than what it was and failed to become what it might have had the city elected to repair the bridge. It’s possible the viaduct was a victim of the wartime shortages of the Second World War or an unfortunate design that was exposed to the destructive effects of the iron horses that had helped spur its construction. None the less, it was among the first of many symbols throughout Joplin which had once been proud monuments to a city which had once burst with pride with expectations of a greater future.

Source: Joplin Daily Globe, Joplin Police Department website, Missouri Digital Heritage