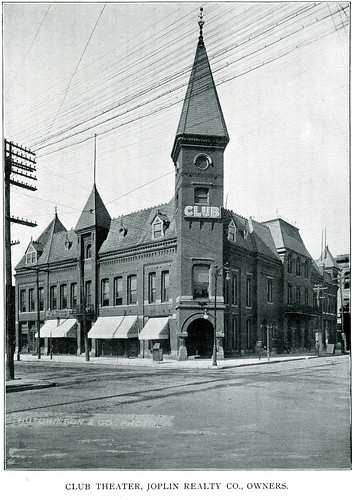

The founding members of the Joplin Auto Club met at the meeting room of the Joplin Commercial Club located at the Club Theatre.

“To cure evils,” was the purpose of the establishment of the Joplin Automobile Club, a branch of the Southwest Missouri Association. In the February of 1911, the city of Joplin was faced with the new problems and dangers of a populace that increasingly turned toward motorized travel in the streets. In response, the city attorney, W.M. Andrews, oversaw a crack down on motor vehicle violations with a veritable flood of arrests and fines. Outrage was immediate. In the quarters of the city’s Commercial Club “bankers, doctors, lawyers and businessmen,” the elite who could afford automobile ownership, demanded answers from Andrews. Andrews, in turn, was blunt. Fourth Street, the city prosecutor decried, had turned into a race track and “only miracles have prevented deaths as a result of fast and reckless driving.”

At issue was a city ordinance which required illuminated numbers on cars to help Joplin’s police department identify and arrest offenders. A number of owners complained that the length of their car identification numbers made adherence an impracticality. Andrews, however, was undeterred and argued of the dangerous driving, “This must be stopped. If there are no numbers on the machines how can an office detect the guilty parties? Within the past two weeks there have been several people injured by autos, and in one instance a woman and two children were thrown from a buggy.” In compromise, Andrews stated that adherence within ten days would result in a dismissal of charges and fines. Unsurprisingly, this was well received.

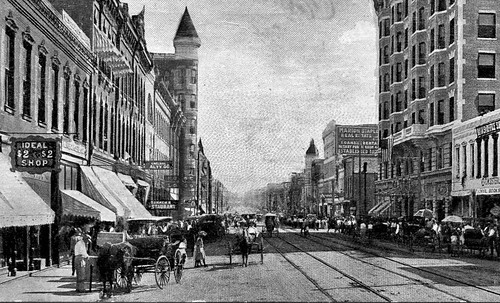

Taken sometime after 1908, this photo reveals that at least 3 years before the creation of the Joplin Automobile Club, Main Street was still mainly a place of horse and buggy.

The car owners were not without a sense of responsibility for their machines of a new century. The Joplin Automobile Club was only part of a series of clubs created throughout Jasper County, with additional clubs associated with the other towns of the county. Approximately 100 men joined that February with the expectation that membership would grow as word and knowledge of its existence spread.

Two weeks later, the men gathered again to elect officers. Taylor Snapp was voted president, Fred Basom and Victor Young, vice-presidents, A.H. Waite treasurer and W.M. Pye, secretary. At the same meeting, the club voted to create reward money for the arrest and conviction of individuals who sought to ruin the enjoyment and lives of car owners. $100 for a car thief, $25 for someone stealing a part of a car, $10 for anyone who cut a tire or threw rocks at a car or its occupants. Interestingly, the club also voted to encourage a crack down on teamsters, who “persist in taking the entire road and who refuse to permit automobiles to pass” in violation of state law. It was Snapp, in this capacity as president who later spoke for the club after a car accident resulted in the creation of Joplin’s first motorcycle police officer. In short, however, the Joplin Automobile Club came into existence as a means for mostly wealthy men to protect their interests in the new and expensive world of car ownership. The distinction of car ownership would fade eventually with the production of cars affordable by all, such as the Ford Model T.